IWASAKI Hirotoshi

Rotoscoping, an animation technique that uses a device called a rotoscope to create a series of images traced from live-action video, was invented in the 1910s and has been used in modern animation production ever since. In this article, rotoscoping researcher IWASAKI Hirotoshi explores the origins of the word “rotoscope.”

This article is a report on the research I conducted on the etymology of the word “rotoscope,” which can refer to a technique used in animation and filmmaking and to a device that facilitates this technique, and also on the results of this research. Although I am describing it as a report at the outset, I do not intend to write it in the style of a formal report, because I am afraid that my focus on the origin of the noun “rotoscope” in the context of animation studies is already too geeky, and I would like people to be able to read it casually as if they were reading an essay. However, as a rotoscope researcher, I would also be happy if these readers could learn something about the technique of rotoscoping itself. Therefore, I would like to begin with a brief explanation of what rotoscoping involves, followed by a step-by-step discussion of my research and results. If you are already familiar with rotoscoping and just want to learn about the results, please feel free to skip past the discussion to the summary at the bottom.

Rotoscoping is a technique invented in 1915 by Max FLEISCHER in order to create animated sequences primarily by tracing live-action footage. The invention came at a time when the industrialization of animation was beginning to take off in the United States. This was the main reason why rotoscoping was developed. The techniques used by animators at that time were still in their infancy compared to today’s techniques. Max came up with a very rational idea that allowed almost anyone to easily recreate realistic motion by tracing live-action footage.

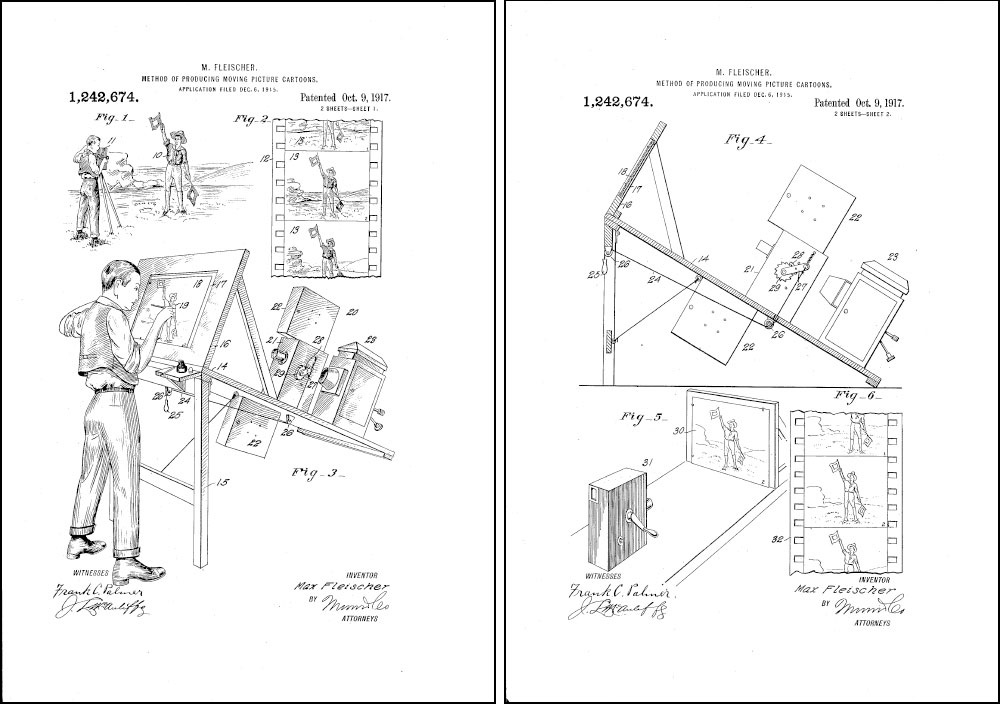

Working with his brothers, Max quickly modified a film projector in order to develop a device that could project a film frame by frame and allow each frame to be traced, which they called a rotoscope. In 1917, Max received a patent on the device, and in 1919 he released Out of the Inkwell, the first animated film created using rotoscoping, which attracted a great deal of attention as the technique was both unprecedented and revolutionary. Later, when Fleischer Studios’ exclusive rights to the rotoscope patent expired, other studios began to employ rotoscoping, including Disney, which used it in 1937 for Snow White.

Since then, rotoscoping has been employed in a wide variety of ways, with major creators such as the animator and filmmaker Ralph BAKSHI1 making use of rotoscopes and the development of a digital version of the software application Rotoshop, created by Bob SABISTON. For a more detailed look at the evolution of rotoscopes, please refer to the article “Henyo suru rotoscope” (The changing rotoscope) in the MACC (https://macc.bunka.go.jp/469/) (in Japanese) or see my own article.2 The problem is that although rotoscoping is now in common use in both the commercial and experimental animation fields, well over a century after the invention of the technique, the origin of the word “rotoscope” remains unclear.

For instance, although we often come across phrases such as “named the rotoscope” or “called rotoscoping,” the crucial etymology is rarely mentioned. It is as if nobody even wonders about it.

The biggest mystery lies in the fact that, despite the absence of the word “rotoscope” throughout the patent application submitted by Max FLEISCHER for the patent of the rotoscope, the name has nevertheless become established. The heading of the application reads “Method of Producing Moving-Picture Cartoons.”3 The application, consisting of illustrations of rotoscopes and text, begins with a self-introduction, “I, Max FLEISCHER, a citizen of the United States,” followed by the declaration, “have invented a new and Improved Method for Producing Moving-Picture Cartoons,”4 and then continues with an explanation of the novelty of using the rotoscope in comparison with conventional animation production and specific apparatus. Moreover, as HOSOMA Hiromichi has pointed out,5 although the rotoscope’s characteristics, including its metamorphosis and grotesqueness, and its method of operation are also clearly described, the terms “rotoscope” and “rotoscoping” do not appear at all in the final patent claim.

While there is no accurate information on the etymology anywhere, let’s consider some promising points from the investigation so far. First, I’d like to start by breaking down “rotoscope” into “roto-” and “-scope.” The term “scope” can mean “to see” or a “projector” and is commonly used in the names of optical toys and devices. The problematic part is the origin of “roto,” which is unknown. One possibility that comes to mind is “roto,” meaning “rotation.” The rotoscope was originally a device made by modifying a movie projector, and it could be speculated that the origin is a literal translation related to either “film rotation” or “projection” at the time of tracing and screening. The naming rationale may be simple, but that may exactly be why it could be a candidate.

The other thing worth noting is the existence of optical devices that share the same name, such as the rotoscope projector, which I came across during my research. Examples of these machines can be found here and there both before and after the rotoscope that Max invented. For example, there was a cinematograph called the PHOTO-ROTOSCOPE that was sold in 1898 by W.C. Hughes & Co., a London-based company that mainly manufactured magic lanterns.6 In addition to that, there was a device for eye examination named the Roto-Scope, which was invented sometime after Max’s rotoscope. These devices were made at different times and for different purposes, but they all shared essentially the same name. What is the significance of this fact? Could it be that the name “rotoscope” was not particularly unusual at the time and that it was widely used as a general term? If that was the case, then it would explain why Max did not include the name rotoscope in the patent application he submitted and why he did not register it as a trademark…

Although I could make some assumptions, I was unable to find any solid evidence regarding the etymology of the word, so I stopped my research in order to concentrate on movie production. (I apologize for being late to mention this, but I am first and foremost a filmmaker rather than a researcher, and I work with rotoscopes.) Later, I had a conversation with the video journalist OGUCHI Takayuki, which prompted me to return to the task again. Mr. OGUCHI said that the “roto” in rotoscope could be the same “roto” as in rotogravure, a type of intaglio printing process using a rotary press.7 This had been a blind spot for me. I also learned that before he began creating animations, Max FLEISCHER had worked for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in Brooklyn, where gravure printing was used in the newspaper photoengraving process, and he had mastered the technique there. This conversation turned on a switch in my mind and I decided to resume my research. However, there was a problem. Even if I looked into the matter again, I probably wouldn’t be able to get any more information without actually going to the United States, but at the time the world was in the grip of a pandemic. Then the solution dawned on me. Why not just ask the studio directly?

These days, Fleischer Studios no longer produces animation, but concentrates on managing the licensing and certain other aspects of some of the characters created by the studio such as Betty Boop. Due to the studio’s decline in its latter years and the issues surrounding its acquisition, I didn’t know how much of the old materials and records they still retained, and I didn’t even know if I would get a reply, but nevertheless I sent an email in the faint hope that they would respond. To my considerable surprise, I received a reply by email the very next day, saying, “I will check to see if anyone can answer your question.” After that, I spent a few days in an upbeat mood, wondering why I hadn’t asked the studio directly at the outset. Then the answer came in.

This time, the email stated simply, “I asked around, but I couldn’t obtain any information beyond what I could find on the Internet.” For a few moments, I was at a loss for words at this unexpected response. The person provided some insights, but these didn’t extend beyond the scope of my expectations or research, and so my re-research quickly went back to square one.

If even the staff member in charge of history at Fleischer Studios couldn’t figure it out, I thought I might finally have come to a dead end, but a follow-up email somewhat rekindled my hopes. The staff member was able to introduce me to Ray POINTER, a leading expert on Fleischer research. Although I was feeling dizzy at this unexpected sequence of events, I hurried to contact this new lead.

I informed Ray POINTER about the history of this project and of the three candidates I was considering as possible origins of the “roto” in rotoscope (namely rotation, rotogravure printing, and rotoscope projector), and asked him for his opinion. Despite my sudden inquiry, Ray POINTER responded very courteously, and even shared some extremely thought-provoking opinions and materials with me. I would like to take the opportunity provided by this report to express my gratitude to him. In conclusion, however, I regret to have to say that his reply was also, “I don’t know for sure.”

Looking at the conclusion alone, the results of the re-research also turned out to be rather disappointing. In short, I found out that we don’t really know very much. However, this time, thanks to the cooperation of Fleischer Studios and Ray POINTER, I was able to come up with some answers, so I can expect to make some progress (or at least I would like to think so). One important finding was that the three theories I had proposed coincided almost exactly with Ray POINTER’s own opinion. Of course, these theories are only guesses, so it is possible that the truth of the matter differs from all of them. However, they seem to be the most plausible explanations for the etymology of “rotoscope” I have come across so far. Therefore, I would like to conclude this article by summarizing these three possible etymologies of the word “rotoscope,” based on the combined views of Ray POYNTER and myself.

《Three possible etymologies of the word “rotoscope”》

(1) The theory of derivation from “roto” meaning rotation

This theory states that “rotoscope” is related either to the rotation (= roto) of the film used to trace plus seeing (= scope), or else to the rotation (= roto) of the film used to trace plus projecting (= scope) in order to see the film.

(2) The theory of derivation from rotogravure

This theory states that rotoscope is derived from the “roto” of rotogravure, which is a type of intaglio printing process. When Max FLEISCHER was working at The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in Brooklyn, the rotogravure process was being used for newspaper photoengraving, and Max mastered the technique there. There are also similarities between the process of plate making and the process of rotoscoping, which transfers images from film onto paper.

(3) The theory of derivation from rotoscope projector

This theory states that the term “rotoscope” itself was already in common use at the time, and that this term was applied as the name of the technique.8 This would explain why the patent application submitted by Max FLEISCHER did not mention the word “rotoscope” at all, but instead specified a “Method of Producing Moving-Picture Cartoons.”

At present, these three seem to be the possible theories as to the origin of the word “rotoscope.” Regarding (2), derivation from rotogravure, which was advocated by OGUCHI Takayuki, Ray POINTER points out that it seems to be a credible explanation, but continues, “It is also possible that the existence of the rotoscope projector led to the general introduction of the term.” Personally, I still think that (3), derivation from rotoscope projector, may have been involved in some way given the evidence that Max did not include the name “rotoscope” in his patent application. But in the end, I have to say that the information at present remains too uncertain to point to the true etymology of the word. In his reply to me, Ray POINTER wrote the following about this situation, based on society in the late 19th and early 20th century, when these technologies were being introduced.

One of the things that makes it difficult to make definitive statements about such matters is that events occur in parallel, with different people coming up with similar ideas or creating similar expressions at the same time. The origin of the use of rotoscoping as an animation technique has not been questioned in the past, so we can assume that the name has come to be used as a generic term in the same way that Kleenex is used to refer to tissues in general, despite it being a trademark name.

Just as when photography and film were invented, the period when rotoscopes were developed was also a time when similar ideas and expressions were being created simultaneously. If rotoscopes were as common as Kleenex, it would be difficult to determine the origin of the term. I was hoping that this research would provide some confirmation, but I didn’t expect to find out more about the depth of the problem.

Once again, to those of you who have read this far, I am afraid that the results did not meet your expectations, but I hope you will look at them with an open mind. Since I am currently focusing on film production activities, I will put my research on etymology to rest here. I may resume my research again at some point, but if anyone is interested in conducting their own research after reading this article, I would be very grateful if you would do so and let me know if you are able to obtain or confirm any findings. Lastly, I would be delighted if you developed even a passing interest in rotoscoping after reading this article.

notes

*URL links were confirmed on August 18, 2023.