IWASAKI Hirotoshi

Organized by Warehouse TERRADA as an art event aimed at connecting domestic and international art scenes and promoting international cultural tourism, TENNOZ ART WEEK 2024 was held from Thursday, June 27, to Monday, July 15, 2024. Contemporary artist Tabaimo, in collaboration with three internationally renowned animation artists, presented her latest installation work, Touch on an Absence, as the centerpiece of the event that also featured a rich program for art professionals visiting Japan for the art fair Tokyo Gendai. The exhibition consisted of a video installation encouraging active viewer movement, as well as screenings of individual video works by each artist. It was presented in a tour-style format, with multiple viewers beginning their journey simultaneously. Here, we report on this experimental work, which can be described as a theatrical installation that reimagines Warehouse TERRADA as its stage.

The opportunity for this exhibition stems from when Tabaimo served as a member of international juries at the 2023 New Chitose Airport International Animation Festival. This festival, which receives over 2,000 submissions annually from around the world, began as the world’s first film festival held inside an airport, primarily in the theater within the New Chitose Airport terminal building. It celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2023 (the author also serves as a jury member for the short film category of the festival).1 At the festival, Tabaimo reached out to the three artists she had nominated as part of the international jury, leading to their collaboration in this exhibition. The participating artists are John SHAFFNER from the United States, Lea VIDAKOVIC from Serbia, and Stephen VUILLEMIN from France. Each has received acclaim at film festivals worldwide while excelling in fields beyond short animation, such as painting, comics, and academia.2

Artists active in animation film festivals are often referred to as independent animation creators. The term “independent” can imply a counter position to the mainstream or the autonomy of individual creators who handle most aspects of production on their own. While the definition is somewhat vague, they typically create short films that reflect personal worldviews rather than catering to the market. Although some independent creators have recently crossed into the mainstream, their recognition remains limited to specific circles. In other words, despite the abundance of talented animation creators around the world, many remain largely unknown. To broaden this horizon while establishing new perspectives and evaluation criteria, the festival invited Tabaimo to participate. However, neither the author nor the festival staff anticipated what would follow. We earnestly hope that the connection between these creators, who primarily operate in the seemingly distant yet closely related fields of film and fine art, despite working within the same medium of animation, will be embraced as a promising avenue for the future development of animation. Now, let us explore how this installation took shape step by step.

In organizing this exhibition, Tabaimo aimed to evoke fantasy and narrative by using animation as a medium to introduce water and living creatures, which are strictly prohibited in the art storage space of Warehouse TERRADA. The narrative, considered one of the exhibition’s crucial elements, will be discussed later. First, let us explore the display composition of Touch on an Absence.

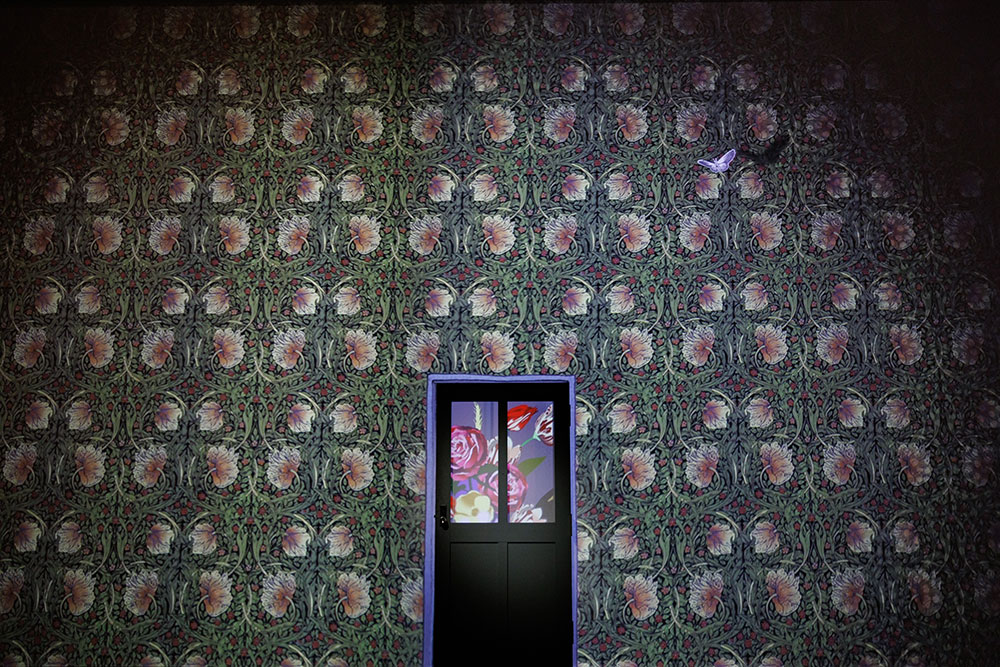

The exhibition is divided into four main areas. In Area 1, a huge screen appears on the viewer’s left. A projection of botanical-patterned wallpaper covers the screen, with a physical door installed near the center. On the door’s window, VUILLEMIN’s floral animation plays, while a white butterfly flutters around the door. As viewers observe this scene, all lights dim except for guiding lights leading to the next area. The viewers start walking following guiding lights like moths drawn to light. Butterflies and lizards occasionally appear in the light, inviting viewers deeper into the exhibition space as they move counterclockwise with the screen on their left.

In Area 2, the same botanical wallpaper continues to be projected, but now a physical desk and chair catch the viewer’s attention. The desk, with one corner cut off, is positioned so the cut edge faces a screen. On the screen, an image of the missing corner is projected, creating the illusion of a complete desk that combines both the physical and the projected.3 On the desk are miniature pieces of tableware, fruit, flowers, and vases used by VIDAKOVIC to create her stop-motion animation, all illuminated by physical lighting. In this area, the desk and lighting are also projected as images, blurring the boundary between reality and fiction. Eventually, the physical lighting on the desk turns off, and the guiding lights once again lead viewers to the next area.

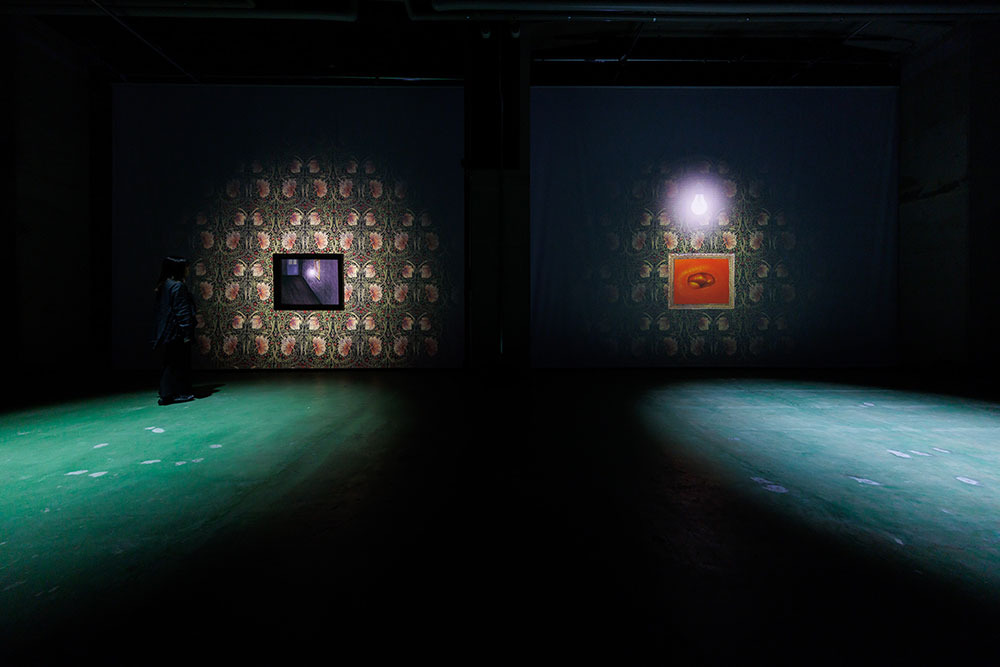

In Area 3, two screens are positioned with the warehouse column acting as their boundary. On the left screen, a physical frame is hung, while on the right screen, an image of a frame is projected. Within these frames, SCHAFFNER’s animations of fruits play, along with nested images of an interior that evoke the exhibition space, heightening the sense of spatial ambiguity. Additionally, the wallpaper is also projected here, indicating that the same wall continues from Area 1.

Shepherded by the guiding lights, viewers proceed to the finale, Area 4, a vast space located within the interiors of the previous three areas. It might be helpful to imagine walking along the outer perimeter of screens arranged in a C-shape before eventually entering the inner space (although it is not exactly C-shaped). Here, projections simultaneously cover the walls and floor, making it difficult to take in everything at once. The wallpaper and frame imagery continue into this space, while animations by the four artists are placed side by side with a striking projection of an elevator moving up and down, reminiscent of the large freight elevators used at Warehouse TERRADA. In the final scene, colorful butterflies fly out through the gap in the door projected on the screen. Beyond this door lies Area 1, the starting point of the exhibition. The white butterfly that vanishes last into the gap is presumably the same butterfly seen fluttering around the door at the beginning of Area 1. This suggests a circular continuity within the space, bringing the approximately 25-minute installation to a close. Following this, visitors proceed to a specially constructed theater space for a 55-minute screening of video works created by the four artists, marking the end of the tour.

Observing the exhibition, one notices that the individual works are not presented independently, but are placed side by side within elements such as walls, windows (frames), and elevators, linking them together. What process led to the creation of such a space?

Regarding the collaborative process for this exhibition, Tabaimo explains that she started by engaging in repeated one-on-one dialogues with each artist. This approach seems to have been intended to elicit three unique responses and outcomes from the artists, all under the shared condition of using animation to introduce elements that could not otherwise be brought into the exhibition space. After reviewing the final outputs, Tabaimo elevated them by incorporating the idea of creating suspense in the space. It can be said that she utilized the responses from the three artists as material to expand the overarching theme into the entire space. Looking at the exhibition overview, the works of three international artists are fragmented yet primarily function as visual elements within the spaces. In contrast, Tabaimo focused on creating the foundational elements: the wallpaper, frames, and elevators. The critical point lies in how she adjusted the sense of distance between each fragment, intentionally preventing viewers from grasping the whole picture, even as something resembling a story seems on the verge of emerging. Perhaps this is the core of the “emergence of fantasy and narrative” mentioned in the exhibition statement.

Then what is a narrative? A narrative can be defined as “how to tell a story” about an event. It is in this storytelling approach that each artist’s unique originality is reflected. The three artists are accustomed to presenting their worldviews through the medium of short animations. It seems that Tabaimo deliberately eliminated elements that could develop stories during her conversations with the artists, sharpened the narrative aspects of each artist, and orchestrated the entire space as a vessel to contain their narratives. The crucial aspect of this exhibition is the tour-style format. During a talk event with myself on July 6, Tabaimo explicitly stated that the exhibition was influenced by her recent collaborations with stage productions, which have become a central focus of her work. In Motsureru suiteki (Tangled drop), a piece created through Tabaimo’s collaboration with France-based circus performer Jörg MÜLLER, one can observe a narrative emerging from the interplay between the temporal and spatial dimensions of animation and the performer’s improvisational physicality. The moving lights that guided viewers throughout this exhibition are also a familiar technique used in theater. Moreover, in stage productions, the audience is considered an integral component that complements the space. Similarly, this exhibition, with its tour-style format, can be regarded as an installation where the viewers themselves function as part of the exhibition space. While it may seem like an ambitious experiment, upon reflection, Tabaimo has been creating spaces that involve viewers since the early days of her career. From this perspective, this exhibition starts to feel like a dark warehouse, reached after wandering through the tatami room of her debut work, Nippon no daidokoro (Japanese Kitchen) (1999).

In such an expansive space, some viewers may have felt a sense of immersion. However, if immersion is defined as the experience of being absorbed into a world through intense focus on a specific object, then the word is not quite suitable for describing this exhibition. This is because, as mentioned earlier, viewers become part of a gigantic installation space the moment they step inside.

This incorporation of viewers into the exhibit is also evident from the movement of the guiding light. The light does not travel in a straight line but shifts in size and meanders, leading viewers to wander left and right. At times, their shadows are projected onto the screen. As viewers gradually adapt to these rules, their behavior begins to change. Some continue to follow the light closely, while others take a step back to observe the bigger picture. In other words, rather than immersing themselves in the space, viewers are compelled to reorganize their perception of themselves, caught between the realm of reality and narrative. The fragmented animation projected in front of their eyes offers the only clues. Although these fragments resemble some sort of story, they neither coalesce into a unified narrative nor reveal the complete picture. As a result, viewers wander through the exhibition space, looking for clues to resolution. In this tangled passage of time, they once again gaze at the fragmented images, seeking something to anchor themselves. Perhaps this is what Tabaimo refers to as “suspense,” from which fantasy and narrative emerge. A key element that contributes to this experience is the presence of paintings-within-paintings, a distinctive feature scattered throughout the exhibition.

Paintings-within-paintings, as the term suggests, refer to depictions of paintings within larger paintings. This concept played a crucial role in the history of Western art from the 15th to the 20th century. It functioned on iconographic, stylistic, and symbolic levels to add layers of meaning to artworks. However, its role shifted with the reevaluation of mimesis (imitation) in the early 20th century. MURAKAMI Hiroya, who studied the role of paintings-within-paintings in Surrealism, succinctly explained this concept: The painting as a whole is considered the primary subject, while the painting-within-a-painting serves as the secondary subject.

Generally, when a painting is placed within another painting, two distinct spaces of different dimensions are created: The space encompassing the entire frame (hereafter referred to as the “parent space”) and the space within the painting-within-a-painting. In such cases, an implicit assumption tends to form—that the parent space is the “primary” and the painting-within-a-painting is “secondary,” or that the former is the “reality” while the latter signifies “fiction.” This assumption arises because the parent space, although fictional itself, strives to approximate reality. By being dimensionally distinct from the “fictional” space of the painting-within-a-painting, the parent space appears even more “realistic.”4

MURAKAMI also states that Dadaist and Surrealist painters intentionally disrupted the relationship between “reality” and “fiction” by leveraging the perceived notion of “parent space = reality / painting-within-a-painting = fiction.”5 It seems that the paintings-within-paintings in this exhibition similarly create a sense of suspense through Tabaimo’s intentional elicitation of disarray.

In Areas 1 to 3, the botanical wallpaper pattern painted by Tabaimo covered most of the screens. These screens were not merely surfaces for projecting videos but also functioned as partition walls, which moved closer to reality despite their fictional nature, transforming the entire exhibition space into the parent space. Within this parent space, fictional spaces of the paintings-within-paintings emerged through physical or projected doors, windows, and frames. As described in the display composition, these paintings-within-paintings projected videos of flowers by VUILLEMIN, fruits by SCHAFFNER, or nested spaces adorned with the same wallpaper. The animations, distinctly different in terms of dimension, contributed to making the parent space appear even more like a physical wall. However, this relationship was inverted when the tour-style installation concluded, and the screening of the four artists’ works started. The videos that had appeared within the paintings-within-paintings reemerged almost identically in VUILLEMIN’s A Kind of Testament (2023) and SCHAFFNER’s In Dreams (2023). What was once perceived as fictional images in the paintings-within-paintings were now presented as reality. This reversal caused viewers to question whether the parent space they had been observing earlier was, in fact, fictional all along.

VIDAKOVIC’s work also introduced a sense of disarray, but in reverse order. In VIDAKOVIC’s case, physical miniature objects were first presented in Area 2. The severed desk suggested that the exhibition space was the parent space, or reality. However, in Area 4, close-up images of those miniature objects appeared within the painting-within-a-painting projected on the screen. What was initially perceived as reality was now presented as fiction. Perceptive viewers might notice that the fruits and flowers projected in this space were the same ones as those displayed earlier in Area 2. This might compel them to revisit the earlier area, but walking backward during the tour was prohibited. Viewers had to rely on their memory to resolve the inversion of reality and fiction on their own.

Thus, the paintings-within-paintings scattered throughout the space by Tabaimo never allow viewers a sense of stability. Instead, viewers are forced to constantly reorganize their understanding of themselves in an ever-fragmented space.

Finally, I should mention that the handout6 distributed at the exhibition entrance, which also contained an intriguing element. Each handout randomly included one of six different message cards, with phrases such as “words explaining the current situation,” “words presenting the laws of nature,” “words that many have used since ancient times,” and “words of philosophers.”7 While some viewers may have noticed the card before experiencing the exhibition, others may have noticed it afterward. Of course, even after noticing the card, viewers were free to decide whether to read it or ignore it. This highlights once again how viewers functioned as part of the exhibition space. A space filled with uncertainty, the introduction of chance, and the choice of action—they overlap in multiple layers to open up the world of “what ifs,” where fantasy and narratives emerge.

The card I received contained the enigmatic phrase “Putting perception within things.” In my case, I only noticed the card after experiencing the exhibition. Had I noticed it beforehand, how would it have changed the perspective or content of this article? I have been contemplating this question while writing but still cannot fully grasp the meaning of the message. Or perhaps the message is intentionally designed to remain elusive. As a viewer myself, I too have fallen into the trap set by Tabaimo. The exhibition title, Touch on an Absence, reverberates like a cryptic echo, hinting at something just beyond reach.

notes

information

Touch on an Absence

Date: Friday, July 5–Monday, July 15 2024

Curtain Time: 11:00 AM / 1:00 PM / 3:00 PM / 5:00 PM / 7:00 PM (90 minutes each)

*11:00 AM / 1:00 PM / 3:00 PM on Saturday, July 6

Venue: TERRADA G3-6F

Admission: Adults 2,000 yen, Students (University, vocational college, or high school students) 1,500 yen, Students (Primary and middle school) 1,000 yen

https://www.terrada.co.jp/ja/news/14648/ (in Japanese)

*URL links were confirmed on September 13, 2024.