FUWA Ryozo

SAGISU Shiro is a prolific master composer and arranger. The first part of this three-part interview features his childhood and privileged background growing up as part of P-Productions, an animation and tokusatsu (special effects) production company run by his father. He then turned to a career in music, making his debut at the age of 21. This second part focuses on how he came to work on various genres of music, including animation and incidental music, and his collaboration with ANNO Hideaki.

Index of Serials

—What was your first professional encounter with animation music? Was it arranging the theme song Meguriai (Encounter) for the animation film Mobile Suit Gundam III: Meguriai Sora (Mobile Suit Gundam III: Encounters in Space) (1982, general director: TOMINO Yoshiyuki)?

SAGISU Yes. I used to belong to the same music agency as INOUE Daisuke,1 who composed music and sang for the film. I had arranged music for some of his live performances. I’d also played as a member of his backing band and done opening performances. He gave me a lot of work. After I moved to a different agency, INOUE looked out for me, calling up to say, “Arrange my next song as well, won’t you?” I didn’t know that the job was for an animation theme song. I learned a lot on site, such as the fact that TOMINO Yoshiyuki and INOUE were university classmates. Of course, I had no prejudices about animation or tokusatsu, partly due to my father’s influence. I just really enjoyed the job. I would keep it strictly secret that P-Productions was my father’s business. At work, I never talked about myself or my background. It was much later that people came to know about it via Wikipedia.

At this time, recording sessions were usually arranged to start at 10 a.m., 1 p.m., 7 p.m., and 10 p.m. I mean, it was the heyday of the industry. The session for Meguriai was set to start at 10 p.m., but I was late. There’d been a press conference to announce the inauguration of BLEND, a new group I formed with YAZAWA Toru, a member of music band Alice who had suspended their activities, and John STANLEY, who later married the singer YAGAMI Junko. It ran late and I had no way of contacting people at the session to let them know. No mobile phones back then. I arrived at the studio at 10:20 p.m. As I’d expected there were all these older guys glaring in the control room. Later, TOMINO complained to me endlessly, saying, “How nice we were kept waiting by the youngest guy…” (laughs).

—From the mid-1980s, you were very active in an astonishing number of genres. Your own projects, of course, but also songs for music idols, J-Pop, animation songs, and incidental music. Does any film, TV, or animation music project stand out for you?

SAGISU Well, it is a difficult question. I had so much work to do. As I mentioned earlier, most studios had four sessions a day so I constantly traveled around various studios in Tokyo. My schedule was hectic, producing thirty pieces of music a month. So I really had no time to stop and reflect on a single project. I didn’t even have time to write invoices, or report on additional work to my music agency. Sometimes, I realized much later, “Oh, I didn’t get paid for that job!” I didn’t even have time to receive sample copies of the work I had done. I apologize, I really can’t think of any unforgettable or memorable projects.

On the other hand, I vividly remember everything about the studios where I did recordings, the participating musicians, and so on. It is because that’s really the only thing I did at the time (laughs). One thing I can say now is that even though I did so much work, I think the music is all really well done, if I say so myself. I can’t single out one piece as the best, but I am still proud of all of the work I did at that time.

—You’ve known ANNO Hideaki for many years, and the music you wrote for his works are a major part of your career in animation and tokusatsu music. How did you first encounter ANNO?

SAGISU I was in charge of music for the original video animation (OVA) Megazone 23 (1985; directed by ISHIGURO Noboru), and Director ANNO was an animator… oops, I’m always calling him Director out of habit (laughs). We worked on the same production, but of course we didn’t meet in person at the time. Our first true collaboration was NHK’s animation Fushigi no Umi no Nadia (Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water) (1990–1991). We were paired by FUJITA Junji, who was the director of King Records in charge of Mobile Suit Gundam III: Meguriai Sora (Mobile Suit Gundam III: Encounters in Space), which you mentioned earlier. FUJITA was also a producer in the early days of King Records’ Starchild label, which specialized in animation. He also established the media mix strategy for animation music. In a word, he greatly developed the animation music business by establishing methods of constantly providing events featuring animation songs, such as renewing the theme song for a single animation many times strategically, having voice actors sing insert songs in order to release them later, and creating related image songs and compilation albums one after another. After becoming independent from King Records, he established the animation Youmex label under Toshiba EMI (later named to EMI Music Japan), and I worked with him on Kimagure Orange Road (1987–1988) as I was in charge of its music. FUJITA and I did many interesting projects together. As Kimagure Orange Road was also a project by Toho Music Publishing (now Toho Music Corp.), I was asked to do the music for the next work that would involve Toho Music Publishing and Youmex. That was Fushigi no Umi no Nadia (Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water) directed by ANNO Hideaki. So meeting Director ANNO was the result of my earlier work, and the arrangements made by our colleagues.

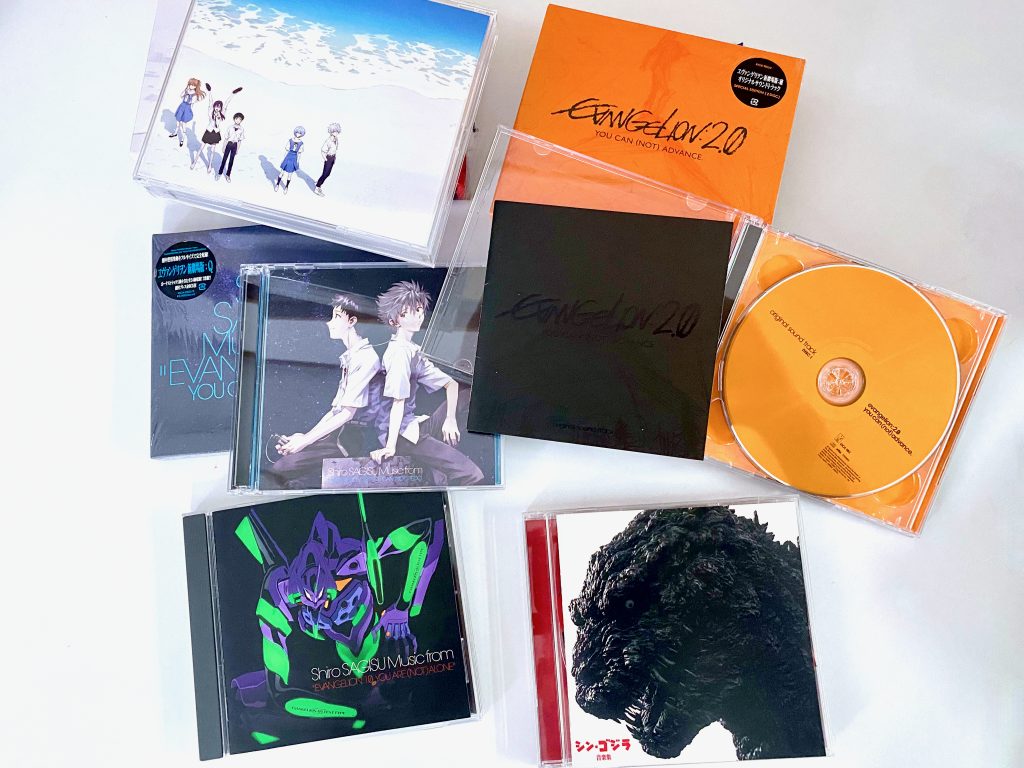

—Have you found something unique in ANNO’s approach to producing music? You worked with him on the Evangelion animation series, the films Shin Godzilla (2016) and Shin Ultraman (2022, directed by HIGUCHI Shinji with general supervisor ANNO Hideaki who was also responsible for planning, scriptwriting, and selecting music)?

SAGISU In Japan, animation or film production staff usually include a sound director, who is responsible for making a music menu and asking the composer to work to it, selecting and deciding where to use sound effects and music, and, in some cases, organizing and supervising voice actors’ recording sessions. The sound director facilitates things by acting as liaison between the director with production team, and the composer with sound effects team. In ANNO’s works, however, there is nobody who plays the role. This is because ANNO himself does that work. He has not changed this policy at all from Fushigi no Umi no Nadia (Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water) to Shin Ultraman. It is so simple, yet it’s rarely used anywhere in the world. In Hollywood, for example, the production system is further subdivided, with dozens of people who each exclusively act as liaison in the fields of music, sound effects, real sounds, dialogue, and so on, respectively.

ANNO’s direct supervision system is enormously beneficial. It’s obviously better if the video creator and the music creator can talk directly, and share their ideas. Larger productions tend to have larger teams, and the more you make efforts to keep things moving smoothly, the more you end up playing the children’s game of telephone. When this happens, what the director or scriptwriter really wants doesn’t reach the music creator’s pen. I believe that what we musicians write must be the music that is playing in the director’s mind. Minimizing the distance between the two is ideal for any production.

—It seems you and ANNO have an unusual approach. Instead of writing to a prebuilt music menu, you and ANNO share your ideas as you write various pieces of music. Then you apply those to the final work, constructing it as you go. This was the case for the Evangelion Shin Gekijoban (Rebuild of Evangelion) series, and especially recent works such as :Q (Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo) (2012) and Shin (Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time) (2021).

SAGISU It is true that we’ve stopped writing music menus unless there’s a special need, and all the music is no longer recorded in a series of recording for a short period of time. Instead, we finish and deliver each piece one by one and then discuss it further. There was also an interval of five years between :Jo (Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone) (2007) and :Q. Then another nine years between :Q and Shin (Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time). Production methods changed as the technology evolved. It’s now possible to upload several gigabytes of music recordings very quickly, and transfer it over the Internet, so that’s changed our approach. In that sense, everything has changed, from transfer methods to delivery methods. I talked earlier about the need to shorten the distance between the director’s mind and the music creator’s pen. Technology has definitely made this easier, along with my own trial and error efforts. Not only does sharing online shorten distance, it conveys my determination to keep working until the director is satisfied. It also makes it easier to explain not having a sound director, and provides practical solutions.

This is not limited to ANNO’s works. It is exactly the same when I work on pop music. How can I minimize the distance between the artist’s mind and my own work? In that sense, there is no difference for me in exploring the brains of MISIA, Director ANNO, and going back further, the brains of TSUTSUMI Kyohei 2 or INOUE Daisuke. It’s the same work. My first priority is to intuitively understand what this person wants to do right now, what they like and dislike…, everything else comes second. I hate the phrase “individual accountability.” The only context where I agree with it is the expression, “satisfaction before accountability.” If I’m not satisfied with something, I’m not going to put my name to it. How can I satisfy others with something I’m not happy with? Of course, Director ANNO shares this feeling more than anyone else.

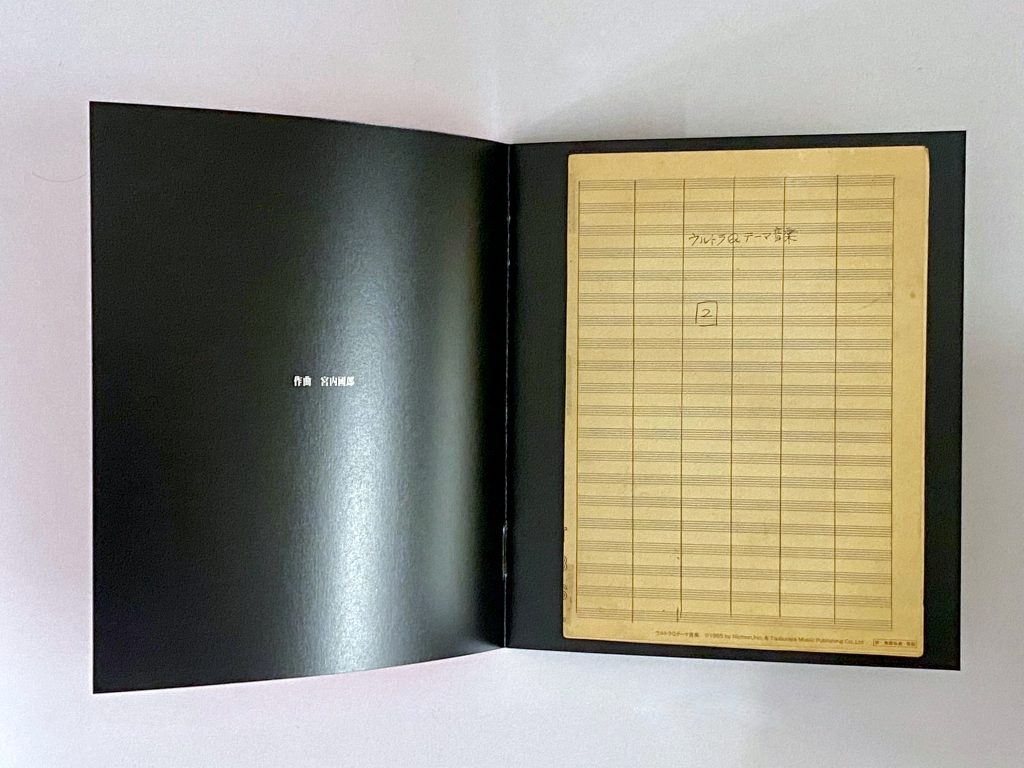

—For Shin Ultraman (2022), the soundtrack was produced by incorporating music by MIYAUCHI Kunio3 for the tokusatsu TV series Ultraman (1966–1967). How do you feel about MIYAUCHI Kunio’s music?

SAGISU Firstly, we share a strong bond as composers from the same jazz field. But when creating Ultraman’s theme song, he was very aware that its music must appeal to children. The series was broadcast on TBS during prime time once a week. It had to be the topic of talk among children at school the next day, and it must keep them excited until the next broadcast. MIYAUCHI’s music had the power to make that happen. He used a technique quite different from his approach to Ultra Q (1966), which also featured monsters but was more of a serious science-fiction drama. Ultraman had the challenging goal of attracting very young people. Its music, including its theme song Ultraman no uta (Song of Ultraman), played a major role in achieving that mission.

Another key aspect of MIYAUCHI’s music is that his incidental music for Ultra Q and Ultraman includes jazz elements, especially modal jazz techniques. Modal jazz was a new music theory created by Miles DAVIS4 with his 1959 album Kind of Blue. While the parameters for conventional bebop and hard bop are “organic changes in chords,” the parameters for modal jazz are innovative “inorganic changes in tone rows alone.” It was a truly revolutionary approach. He presented a method of enabling improvisation by slightly modulating tone rows up and down, instead of making a series of chord changes. MIYAUCHI Kunio was originally a jazz trumpeter. He must have been greatly influenced by Miles DAVIS. He also belonged to the generation that experienced modern jazz’s innovative changes in real time. In particular, the incidental music for Ultraman has many riffs modulated in the modal jazz style. This approach does not use the conventional style of Japanese incidental music that depicts emotions in scenes in an easy-to-understand way, but uses a method of building up a certain atmosphere or seriousness by delicately shifting the pitch of a motif up or down. For people like me, who have been very influenced by jazz, it is easy to understand what MIYAUCHI wanted to do, which I find very moving.

In Shin Ultraman, the main theme for Ultra Q plays at the beginning. The impressive riff is played by electric guitar. Until the early 1960s electric guitars had only been given limited expression. It was The Ventures, The Beatles, and Jimi HENDRIX, among others, who radically changed how we play them. Ultra Q is proof that their influence had reached Japan. The idea of playing the main riff on guitar alone was totally new to Japan at that time. The sounds of the main theme of Ultra Q were astonishing. The musicality demonstrated by this main theme had a great influence on Japanese incidental music and the creators who followed. In other words, MIYAUCHI Kunio is the music creator who advanced and modernized the potential of the electric guitar.

Jazz musicians are very sensitive yet very tolerant toward drastic paradigm changes in performance and instruments. Rock, heavy metal, and hip-hop also change, but their styles are so clear that their basic stance cannot be changed. But as they say, “In jazz, there are no masterworks, there are only masterful performances.” Ah, these are my own words of wisdom! (laughs) Jazz is free to go on changing, even at its core. The fact that MIYAUCHI Kunio, a trumpeter, was able to do such an extraordinary, innovative thing on the guitar is proof that a good jazz musician has a very flexible musical attitude. With this in mind, I included a bonus track on the Shin Ultraman music collection CDs. I think it’s how MIYAUCHI would have rewritten the Ultra Q theme if he’d heard EDM.

Although I also tackled IFUKUBE Akira’s5 score for Shin Godzilla, I had a stronger sympathy for MIYAUCHI’s score. I also felt that as fellow jazz musicians if I’d talked with him, we would have enjoyed a deep conversation. I felt that his music and background was revealed to me through working on Shin Ultraman. Even though he had already passed away, I was able to have a dialogue and interact with him in my mind through the work. It was such a memorable project for me.

—But when the original Ultraman series was being broadcast, your father’s company, P-Productions was making a competing show.

SAGISU Right around the time Ultraman was being broadcast, P-Productions was making Maguma Taishi (Ambassador Magma) (1966–1967). Ultraman was an obvious rival. Fortunately, we had YAMAMOTO Naozumi6 for its music. First and foremost, his melodies were highly accomplished, while his incidental music effectively focused on explaining each scene or situation. His music was so powerful and easy to understand that it drew many children to the story. It is not a question of whose music is better or worse. It is just amazing that although these series were produced in the same era and belonged to the same tokusatsu genre, their overall character was heavily influenced by their respective music. In addition to MIYAUCHI and YAMAMOTO, Ultraseven (1967–1968) had FUYUKI Toru7 and Maiti Jakku (Mighty Jack) (1968) had TOMITA Isao.8 All these creators’ work had such strongly unique personalities. Their music had nothing to do with my earlier condition of traveling from the director’s brain to the music creator’s pen. Instead their pens were capable of standing alone. Regardless of any discussion with their directors, their musical personalities and compositional abilities were overwhelming. Once they were assigned to a project, it practically guaranteed the series would be of the highest quality.

I’m sure they must have had meetings with directors and producers, but having a single meeting or phone call in those days were much more significant than they are now! Unlike today, it was not possible to exchange ideas several times using demos, so each composer was entrusted with a great deal of responsibility. Much heavier than composers are today. Once the work was assigned, there was no choice but to leave it completely in the hands of the composer. That’s a lot of trust and responsibility. And these creators responded to that faith, producing compositions that met their clients’ expectations and eliminated their anxieties. I believe this lies behind the indefinable power of music from the 1960s and 1970s. Not just incidental music but pop music of that era too. Director ANNO loves incidental music from this era, and I totally understand why. It has a quality that we’ve never been able to match. People respond to it in their hearts, even while their head can’t define it. I think you know what I mean.

—Your father, SAGISU Tomio (USHIO Soji), was P-Productions’ founder and president. He was involved in writing manga, operating an animation studio, and producing live-action tokusatsu TV series. There is probably no other creator in the history of Japanese media arts who was active across all of those fields.

SAGISU Thank you. As many people speak well of their children, let me speak well of my father. He should be far better known! I can’t think of anyone else who has written best-selling manga and created prime-time hit series both in animation and live-action tokusatsu. Even TEZUKA Osamu and TSUBURAYA Eiji, who both worked with my father, were not so successful. On the global stage, I can only think of Walt DISNEY.

Because I helped out in his business from the time when I was a child, he and I shared a very strong sense of solidarity, even though we were father and son. That didn’t change after I started working in the music industry. I use the former P-Productions building as a studio. My father’s study is still on the second floor, and there’s an upright piano beside it. When I was writing scores for pop stars in the 1980s, I played that piano to write the scores. My father would be drawing pictures and writing scripts in his study. We often met in the kitchen by chance when we got hungry late at night. Both of us worked through the night. Although we walked different paths, I think we had a similar attitude toward work. He is sometimes described as “the uncrowned emperor,” a somewhat self-serving phrase. But now that manga, animation, and tokusatsu are so highly regarded and accepted as their own culture, I really hope his works and influence will be given the appreciation they deserve.

notes

SAGISU Shiro

Born in Tokyo in 1957. SAGISU Shiro is a composer, arranger, and music producer who works under his birth name. He’s been an industry leader throughout his extraordinary career, working on the front lines for over 30 years since he participated in The Square’s debut album in 1978. SAGISU has created thousands of pieces of music and worked extensively with numerous artists, from pop idols in the 1980s to instrumental artists and more recent singers and artists. He is also active in the field of soundtrack music, including movies and TV. He’s produced a constant stream of astonishing hits over the decades. He has also been active in Europe since the 1990s, running a club in Paris and working with UK and French artists. He became the first Japanese composer to serve as the music director for a Korean movie. Artists he has recently worked with include MISIA, HIRAI Ken, CHEMISTRY, Elisha La’Verne, SMAP, The Gospellers, and HAKASE Taro, and he participated in such works as the Evangelion series, MUSA, CASSHERN, BLEACH, Shingeki no kyojin (Attack on Titan), Shin Godzilla, and Shin Ultraman.

http://www.ro-jam.com/ (in Japanese)

*Interview date: July 4, 2022

*URL links were confirmed on February 1, 2023.

>No. 5: SAGISU Shiro, composer (Part 1)

>No. 7: SAGISU Shiro, composer (Part 3)