Text: MATSUO Nanae (MANGA NIGHT General Incorporated Association) / Editing: SUZUKI Fumie (MANGA NIGHT General Incorporated Association) / Recording, compilation and editing: SAKAMOTO Asato (Whole Universe)

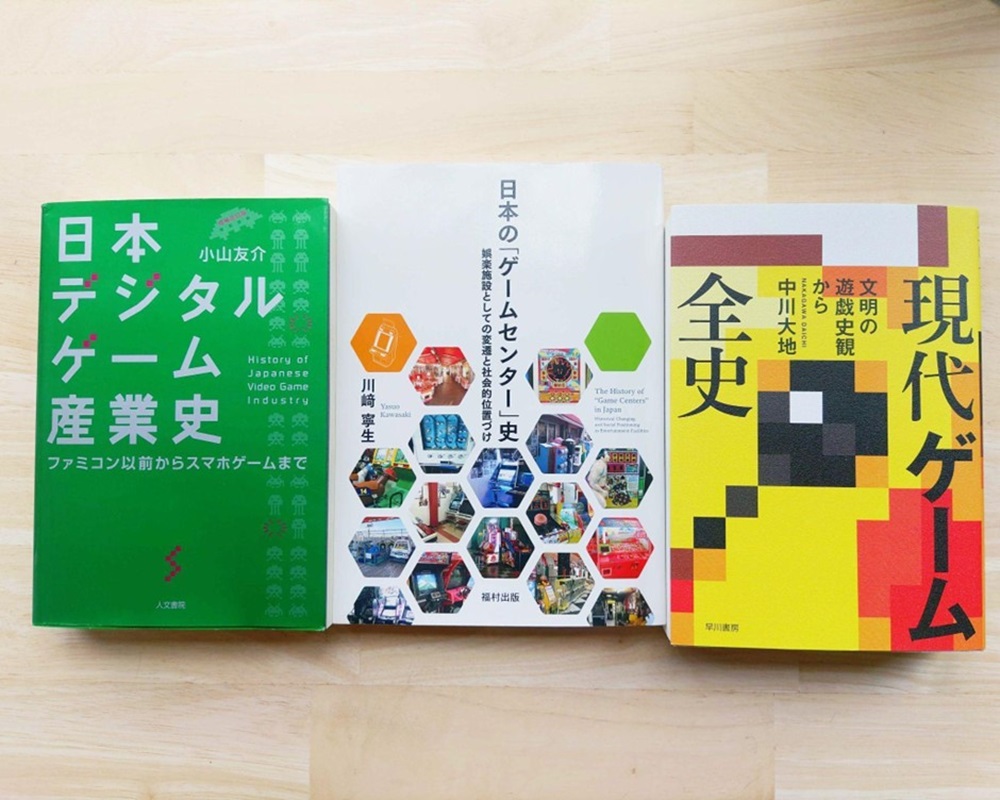

The Agency for Cultural Affairs (Government of Japan) conducted the MAGMA sessions1 as part of the Fiscal Year 2023 Agency for Cultural Affairs Project to Improve Networking and Archival Infrastructure of Media Arts. At the talk session themed “Game shi wo kaku tame no shiryo wo kangaeru” (Considering materials for writing game history), three invited panelists discussed the challenges of writing game histories, how to collect materials that change over time, and other considerations. The three were KOYAMA Yusuke, author of History of Japanese Video Game Industry (Jimbun Shoin, 2016, enlarged and revised edition in 2020), KAWASAKI Yasuo, author of The History of “Game Centers” in Japan: Historical Changing and Social Positioning as Entertainment Facilities (Fukumura Shuppan, 2022), and NAKAGAWA Daichi, author of Brief History of Contemporary Games: From a Historical View on Play and Civilization (Hayakawa Publishing, 2016). This article presents excerpts from the discussion. (Facilitator: YAMADA Shuka)

*The entire talk is available for viewing on MACC’s video archive

YAMADA Please tell us about your research topics.

KOYAMA I specialize in the “theory” of the game industry rather than the “history.” To comprehend the present, one must understand its past development; otherwise, meaningful discussion is hindered. I started writing History of the Japanese Video Game Industry only out of necessity, in order to discuss what kind of industry the game industry is and what state Japan’s game industry is in.

To discuss “what the industry is,” there is a need for fact-based data, and knowledge of the game industry history serves as that data. To understand “what is important,” a framework like industrial theory becomes necessary. I developed both the history and theory simultaneously like two wheels of a cart.

When it comes to the abilities required for writing historical facts, there are three major aspects: “investigation and reporting,” “theoretical analysis,” and “constructing an overview through analysis.” Personally, I have done very little “investigation and reporting.” In History of the Japanese Video Game Industry, I essentially reconstructed existing literature and provided insights by reorganizing various numbers and data gathered from different sources.

For example, to demonstrate the basis for the growing size of game development, I performed labor-intensive tasks such as watching the endings of the Dragon Quest series, entering all the names that appear in the staff credits, eliminating duplicates, and recounting.

History of the Japanese Video Game Industry seems to be the first in the world to document the overall history of one country’s game industry. In the future, when histories of game industries in the United States, Europe, and even a “world game industry history” are written, I would be pleased if my book could be used as a “component” and contribute to lively discussions and writing.

KAWASAKI I am currently researching events related to “game centers” (game arcades), including the era before the birth of the current game centers. The method is an empirical analysis based on qualitative materials obtained from reference literature and field surveys. The foundation of my methodology is rooted in historical methods learned during my university days.

Since the history of games is an ongoing academic discipline and industry, it is impossible to separate its impact on society. As a result, the research field is a mixture of history and sociology.

For example, in Chapter 2 of The History of “Game Centers” in Japan, I conducted a comparative analysis of the game center histories in Japan and the United States. In Chapter 3, I analyzed the factors related to the differences. The focus was on the issues of gambling and juvenile delinquency, where game centers became scrutinized from the perspective of youth protection. I explored why Japan, in comparison to other countries, managed with relatively lax regulations. This involved examining existing studies, analyzing reference literature, political materials such as minutes of the Diet’s plenary sittings, and considering the societal context. Overall, the research heavily relied on documentary sources.

On the other hand, Chapter 6, which covers game corners that spread in dagashiya (small-time candy shops) and toy stores, faced a scarcity of materials, including existing studies. I relied on articles from the industry-specific magazine The Coin op. Journal and conducted interviews through field surveys after taking a historical perspective on the overall situation. While documentary sources were essential for organizing the preliminary stage of considering the societal context surrounding the subject, qualitative research was absolutely necessary as supplementary information due to the predominance of secondary sources.

NAKAGAWA Although I am not a researcher affiliated with academia, as an independent critic and editor, I serve as the deputy editor-in-chief of PLANETS, a critique medium. PLANETS was established as a comprehensive critique magazine that spans various cultural genres and explores connections with culture and society. In 2010, we published its seventh volume, PLANETS vol. 7 (Dainiji wakusei kaihatsu iinkai [Second planetary development committee]), with a feature titled “Game hihyo no sankakukei (tri-force)” (the triangle of game criticism [tri-force]) that looked back on the history of digital games from the perspective of the information social theory.

Based on the discussions there, I published Brief History of Contemporary Games in 2016. Rather than focusing on specific targets or perspectives, I centered the book on digital games as a content genre that ordinary people would think of when hearing the term “game” in Japanese today. Instead of strictly describing historical facts, the book aims to extract the sociocultural significance in an accessible manner, allowing readers, even those not interested in games, to experience the dynamism and allure of the contemporary history they have lived through.

I deliberately use the term “contemporary games” without a strict definition, yet it carries a slightly unique, nuanced limitation. Essentially, it is an adaptation from “contemporary art,” a term that developed in the latter half of the 20th century.

By conceptualizing “contemporary games” as something that, based on information and visual technology, provides new types of play and artistic experiences to humans, I intend the phrase to include not only computer games but also imply board games, tabletop role-playing games (TRPG), and trading card games that developed contemporaneously.

With factual accuracy as the fundamental premise, I meticulously scrutinize each piece of information, selecting and rejecting while juxtaposing both reference literature and various discourses conveying the mood of the times. Extracting insightful knowledge was particularly challenging in compiling my own history of games.

KAWASAKI Arcade games undergo significant changes depending on location and region. The existence and operation of game centers differ between rural and urban areas, and the management of game corners operated as a secondary business by shop owners is entirely different. Considering the diverse ways in which children play, it was impossible to rely solely on reference literature, and I had to turn to qualitative materials.

In future research, to understand how crane games, prize games, and purikura (photo sticker) machines are played, social networking sites such as Instagram and “X” will become the primary source of information. I believe that to see how people enjoy and elevate games as a culture, and how they create communication spaces, relying on qualitative research is inevitable.

Regarding purikura in the 1990s and 2000s, it has been analyzed in the supplement of Game center bunka ron (game center culture theory) (KATO Hiroyasu, Shinsensha, 2011), but 20 years have passed, and the situation has changed. Writing and analyzing a society that undergoes rapid changes over 10 or 20 years is academically very challenging. This is something that needs special consideration in discussions based on specific locations.

KOYAMA In the case of smartphone games, data doesn’t tend to linger. Currently, on Steam (a platform for PC games), around 10,000 titles are released annually, but for many, there’s little data preservation. Moreover, it has become challenging to encompass everything within the framework of Japan as a country. While I was able to publish an enlarged and revised edition of History of Japanese Video Game Industry in 2020, a third edition would be difficult.

NAKAGAWA I agree. Works from the 1980s and 1990s are still kept as physical items, making them relatively easier to preserve. For instance, there are various cases of dynamic preservation by Ritsumeikan University’s Game Archive Project and enthusiasts. In particular, Joseph REDON’s Game Preservation Society puts effort into preserving PC games from the microcomputer boom era, and they have meticulously organized methods for managing items like floppy disks.

In contrast, what I found most challenging when writing game history was the mobile phone games for feature phones from the 2000s onwards. Firstly, many of the production companies from that time have disappeared, and even when attempting to contact people through intermediaries, it was often difficult to meet them. Especially, older titles from before the advent of major platforms have become increasingly difficult to trace. The preservation of online-era games has been a topic of discussion in the game archive suishin renraku kyogikai (consortium for game archive) 2, but the situation persists where an appropriate solution is yet to be found.

KOYAMA In my case, writing about the industry history made certain aspects easier. Information such as sales data, model data, and the introduction of various technologies is readily available. However, through those methods, information about how the games were played is not preserved.

NAKAGAWA Regarding following the times through materials, we can indirectly trace information through magazine media. After thoroughly pursuing information from related magazine media, it might be worth investigating what to do next and determining how far we can trace before reaching a point where it becomes challenging.

KAWASAKI When it comes to the difficulty of archiving, arcade games are indeed a significant challenge. Firstly, the actual physical items are inherently challenging to preserve. There are technical challenges related to repairing, preserving, and maintaining the cabinets. Additionally, considering the variety of games, including medal games, prize games, purikura, and others, ultimately, the preservation efforts are led by individual industry organizations and facilities.

From a material perspective, prize games pose a particularly challenging issue. The fundamental problem is that the prizes themselves are not preserved. Without records in industry magazines or photographs, there are no materials available. Additionally, many prize games are not led by companies, and in such cases, without on-site photographs, there is no record left. Figuring out how to archive such unique items becomes a significant challenge.

Moreover, another inherently difficult issue is related to so-called pirate versions or copy boards, including records of copied game machines. Some illegal elements have had a significant impact on game culture and society. However, for companies and industries, preserving the history of such elements is exceptionally challenging.

YAMADA Listening to the discussion, I realized that there are different consensuses of “games,” and despite the vast amount of available materials, each exists individually. How to use them for research or how to discover what kind of materials are needed is a conversation that needs to be considered together, involving both those who create games and those who play them.

KOYAMA Since I am not a specialist, I omitted discussions about the content of games as much as possible. The developmental and influential histories of game genres are undoubtedly essential for those studying game design in the long term, but there’s still a lack of materials and research. I think it might not go beyond nostalgic talks.

KAWASAKI Discussions about game history, including nostalgic talks, tend to become personal histories. It’s necessary, including myself, to consider how to academically incorporate personal histories into game history as a whole. However, to do that, we need to look at not just what we personally like but also what happened societally as a whole.

NAKAGAWA When I was writing Brief History of Contemporary Games, there was actually one underlying theme. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, there was a period when an analog game called “Play by Mail,” which was played by hundreds or thousands of players in remote locations using postal service, thrived as an adjacent genre to tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs). I was intensely into this during my junior and senior high school years. There was always an ambition deep within me to somehow convey this gaming experience to future generations.

Driven by the passion to convey this niche and personal experience as a universal theme to as many people as possible, a sense of mission arose to grasp the overall picture of “games.” Consequently, my interest shifted towards understanding the relationship between my favorite genre and others, as well as its position within the societal context.

What I want to convey to those aspiring to study game history in the future is the importance of considering how the “core” of their passion can be communicated to others. There are already well-established compasses in previous studies that can serve as clues. I encourage individuals to delve deeply into their unique experiences while, at the same time, maintaining a perspective that tries to oversee the entire landscape. I hope they can find their own narrative approach in the process.

Footnotes

KOYAMA Yusuke

Professor at the College of Systems Engineering and Science, Shibaura Institute of Technology. Published History of Japanese Video Game Industry (Jimbun Shoin) in 2016, depicting the rise and fall of the digital game industry in Japan. Published an enlarged and revised edition in 2020. Co-authored works include Studies of Content Industries: Mixture and Diffusion of Japanese Content (University of Tokyo Press, 2009) and Media content sangyo no communication kenkyu (Communication research on media content industries) (Minerva Shobo, 2015).

KAWASAKI Yasuo

Lecturer at the Graduate School of Core Ethics and Frontier Sciences, Ritsumeikan University. Visiting researcher at the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies. Conducts research and investigations on the social awareness surrounding the relationship between Japan’s gaming culture and society. Published The History of “Game Centers” in Japan: Historical Changing and Social Positioning as Entertainment Facilities (Fukumura Shuppan) in 2022.

NAKAGAWA Daichi

Critic, editor. Deputy editor-in-chief of the critique magazine PLANETS. Published Brief History of Contemporary Games: From a Historical View on Play and Civilization (Hayakawa Publishing) in 2016, depicting how games encountering information technology have influenced society. Involved in the game archive suishin renraku kyogikai (consortium for game archive).

YAMADA Shuka

Freelance writer. After working as an editor for a children’s game magazine, currently writes primarily about games and movies for game media such as IGN Japan. Also involved in creating game scenarios. Contributed to The Deep Guide to Indie Games (P-VINE, 2022), a comprehensive introduction to indie games.

*Round-table discussion date: October 18, 2023