SATO Emi

The Department of Intermedia Art in the Faculty of Fine Arts and the Global Art Practice established in the Graduate School of Fine Arts at Tokyo University of the Arts. In the first part, we spoke with the respective faculty members, HACHIYA Kazuhiko and MOHRI Yuko, about education in media art and the Japan Media Arts Festival. In the second part, we delve into how practical art education, which is essential, has been implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic.

—I’d like to inquire about the classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Around the spring of 2020, many universities had transitioned to online learning. How did Tokyo University of the Arts (referred to as “Geidai”) respond?

MOHRI It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Mr. HACHIYA was the quickest to adapt during the pandemic. He took the initiative in disseminating information about how to use Zoom and the methods for online classes.

HACHIYA Since the university was in its spring break, we were able to act promptly. When we were considering how to handle the next academic year, the situation worsened rapidly. Around March, a working group for online classes, led by about five university-wide faculty members at Geidai, was formed, and I became one of them. Initially, we focused on figuring out how to conduct classes online. Simultaneously, as our university often relied on paper-based documents and face-to-face meetings in various internal meetings, I proposed alternative methods and created explanatory materials.

MOHRI We established rooms for online classes.

HACHIYA We enlisted the help of the Art Media Center within the university, which is engaged in research activities related to information media, and thought about which tools would be suitable for online classes. We gathered equipment in dedicated rooms, which were then loaned to the professors. The budget allocated by the Ministry of Education (Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) for purchasing equipment proved helpful in this endeavor.

MOHRI There were also experimental online classes that were unique to Mr. HACHIYA.

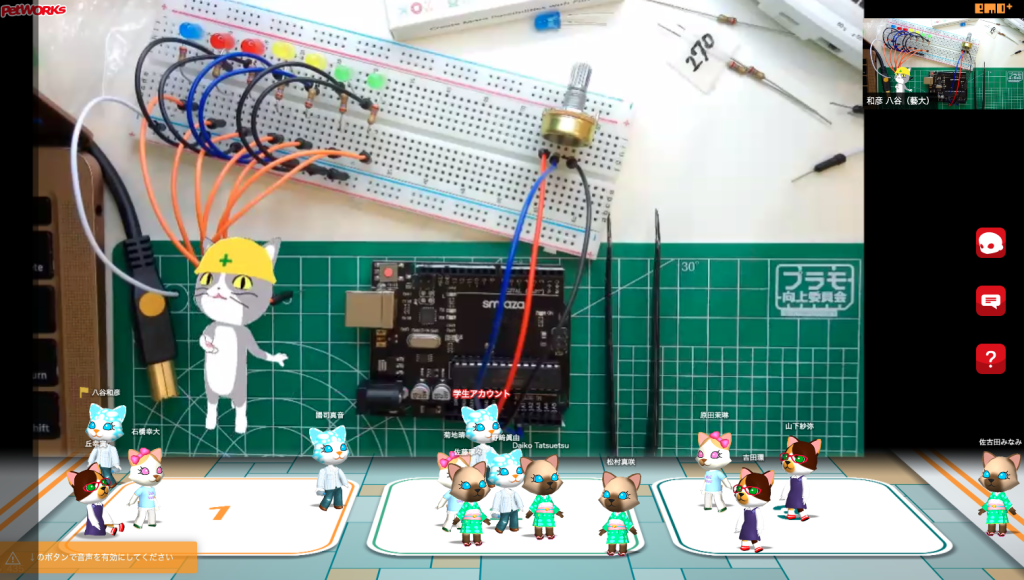

HACHIYA In addition to the camera capturing faces, we used a separate camera to stream the whiteboard for writing. Personally, I conducted classes from home using avatars, incorporated robotic responses, and conducted various experiments using mixers, switchers, cameras, etc. We took inspiration from VTuber livestreams at that time. I also attended classes by music teachers and consulted with professors from the Department of Film and New Media. It was great that interactions with other disciplines were born during that period.

—I thought lectures could be conducted online, but practical work must have been challenging.

MOHRI The Global Art Practice I belong to aims for international exchange, so it was quite difficult. Before the pandemic, we had joint classes involving travel to affiliated schools abroad, but that became challenging. When I was wondering what to do, I recalled the history of media art. In the 1990s, there was a focus on the field of “telepresence,” which involved physical communication systems that allowed remote interaction as if using one’s own hands. Unlike today, there were no high-precision cameras or large-screen monitors, but the theoretical aspect was emphasized, exploring how embodied communication could be achieved. Now, with significantly advanced devices, I thought about how to incorporate this methodology into our classes.

So, rather than just looking at each other on screens like regular video communications, I devised a mechanism where my image and the student’s image on the other side of the screen would overlap. In 2021, although it was difficult for all students, the staff were allowed to travel, and we were dispatched to France for interactive classes. We engaged in Contact Improvisation on a stage called the “Synchronic Portal.” The students in Japan performed improvised movements, and the partner in France, visible on the screen, reacted to it. As a result, their images overlapped and intertwined on the screen.

—I was surprised that such things could be done in class. In adversity, the knowledge of media art was maximally utilized. What kind of class was it?

MOHRI It took place within the framework of the “Art Practice” class. It was a workshop-style class where students practiced what kind of expression they wanted to make their own. Personally, I focus on collaborating as something noteworthy in school. Once you graduate and become independent, you inevitably become lonely, so while you’re at school, let’s do something together (laughs). This method increased the students’ concentration.

I don’t think anyone is thinking of doing media art, but it naturally becomes media art due to the environment. However, the preparation is challenging. Despite rehearsing multiple times in Japan and spending a lot of time preparing, the actual class was only 2 hours. It was a grand project.

HACHIYA In a class, there’s this sense that it has to be a success because the students are waiting at this time. I think what Ms. MOHRI did was amazing. At the Department of Intermedia Art, in the 2020 academic year, almost all classes, including practical ones, were online. Fourth-year undergraduates and second-year master’s students, before their graduation projects or completion works, have “Work in Progress (WIP) exhibitions,” which are like pre-presentations, but even that went online. Exhibition experience is also an essential element as an artist, so before the pandemic, we used to have in-house exhibitions quite often. Not being able to do that was quite a blow. We realized it was problematic to continue like this, so the following year, we gradually started to bring back the WIP exhibitions and practical classes in person. However, some lectures are still partly online. For electronic work classes, doing them online has the advantage of being able to show enlarged details of the hands at work, so in a way, that turned out to be beneficial. When you think about it, the impact of the new coronavirus may not have been all bad.

I also like some of the works created by Ms. MOHRI during the pandemic. In the 2022 exhibition at the Garden Hall in Yebisu Garden Place titled Piano Solo, she recorded the environmental sounds during quarantine at a travel destination abroad. Subsequently, she transformed these recorded sounds into a piano composition that is played automatically.

MOHRI Did you see it? Thank you so much! In 2021, I went to the Netherlands for a performance, and there were quarantine periods in both countries before and after the trip. I recorded sounds like bird songs and the sound of playing tennis coming from outside the hotel window. When these sounds are played back, they are live-transformed into a 12-tone scale, and an automatic piano plays them. That’s the piece. In around 2021, my productivity in creating works increased significantly. The number of exhibitions per year also increased. Maybe the imminent danger somehow sparked motivation.

HACHIYA It’s a result of thinking about what can be done when the situation changes dramatically, and what can be done with the limitations imposed. There was also a feeling that there was no choice but to create.

MOHRI During the pandemic, I also learned to install works remotely.

HACHIYA In media art, there used to be a premise that artists had to be present for exhibition setups. However, due to the circumstances, remote installation became inevitable, and the skills of staff who install works on-site also improved.

—This kind of reflection of societal conditions in artworks is unique to media art.

HACHIYA Engaging in media art activities can be quite applicable, so it might come in handy in life someday. Learning something with a media art approach has value as a skill in itself.

HACHIYA Kazuhiko

HACHIYA is a media artist and a professor in the Department of Intermedia Art, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Born in 1966 in Saga Prefecture. After graduating from Kyushu Institute of Design (now School of Design, Kyushu University), HACHIYA worked at a consulting company before founding PetWORKs Co., Ltd. His notable works include “Inter Dis-Communication Machine” (1993) and “Seeing Is Believing” (1996). He also initiated the “OpenSky” project (2003–), where he prototyped and flew an aircraft inspired by the flying machine in MIYAZAKI Hayao’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). HACHIYA developed the email software “PostPet.” Recent solo exhibitions include “‘M-02J’ and ‘HK1’ – Fascinated by Tailless Aircraft” (Aichi Museum of Flight, 2022). He also produced an exhibition titled “HomemadeCAVE #3 Portalgraph showcase” (GINZA SIX, 2022), among others.

MOHRI Yuko

MOHRI is an artist and an associate professor in the Global Art Practice, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Born in 1980 in Kanagawa Prefecture. She completed her studies in the Department of Intermedia Art at the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. MOHRI creates installations and sculptures that focus on “events” that change based on various conditions such as the environment, rather than approaching composition in a constructive manner. Some of her recent solo exhibitions include “Neue Fruchtige Tanzmusik” (Yutaka Kikutake Gallery, Tokyo, 2022), “I/O” (Atelier Nord, Oslo, 2021), and “Parade (a Drip, a Drop, the End of the Tale)” (Japan House São Paulo, 2021). She has also participated in notable group exhibitions such as the 23rd Biennale of Sydney (Sydney, 2022) and the 34th Bienal de São Paulo (São Paulo, 2021).

*Conversation date: January 25, 2023

>File 3. Tokyo University of the Arts: HACHIYA Kazuhiko×MOHRI Yuko [Part 2]