KANOH Seiji

Before the term “animation” took root, films we think of as animations today were known as “manga eiga (manga films),” “senga (line drawings),” “doga (moving pictures),” and so on. In 1958, when the term “manga film” was still in widespread use, MIYAZAKI Hayao saw Hakujaden, Japan’s first full-length color animation, and this marked the beginning of his career in animation. This article will take a step-by-step look at the process of popularizing the term “manga film” in Japan, and how MIYAZAKI was influenced by his predecessors who pioneered the field of animation.

MIYAZAKI Hayao 1 has often referred to his own works as “manga films.” For example, he has made statements such as the following:

I feel that at the end of a manga film, the audience should feel liberated, and the people who appear in the film should be liberated as well. I like it when the people appearing in the film become innocent.

TOMIZAWA, Yoko (ed.), Mata aeta ne! (I met you again), Tokuma Shoten, Animage Bunko, 1983, pp. 145–146

We live in a real society that we can’t escape from with selves that we can’t escape from, don’t we? However, if only we could escape from all our inferior complexes and difficult relationships and live in a freer and more easygoing world, we could become stronger and more heroic. You probably have the feeling that you could be more beautiful and kinder, and that your existence could be meaningful. This applies to young and old, and to women and men alike…

Ibid, p. 148

Manga films are a way of depicting lost possibilities. I think there are few animations today that possess the kind of vitality that would allow us to call them manga films. (…) I have always felt that manga films were supposed to be more interesting and exciting.

Ibid, p. 149

“Manga film” is a term rarely heard today, but it is clear that MIYAZAKI finds a positive significance in talking about it. It could be considered an indicator of the way ahead for him.

There was once a time when animation was known as manga film. However, when that was and for how long it lasted is unclear.

In the first place, it is difficult to define precisely what a “manga film” is. It is unclear whether or not it is a general term for “animation” works, or it refers to the technical classification of what is so-called hand-drawn cel animation, or it is something restricted to certain target age groups, themes, or the entertainment value of expression. All of these aspects are ambiguous and unclear.

So, first of all, I would like to trace the course of the changes in this nomenclature as a premise for proceeding with the discussion.

During the years 1910 and 1911, many short animated films in a series entitled Dekobo Shingacho (Dekobo’s New Picture Book) were shown at theaters in Japan. According to The History of Japanese Animation (co-authored by YAMAGUCHI Katsunori and WATANABE Yasushi, edited by Puranetto, Yubunsha, 1977), these films were apparently modified versions of the Fantoche series and other series beginning with Fantasmagorie, produced by Émile Cohl in France in 1908.

Dekobo was originally the name of a popular character created by manga artist KITAZAWA Rakuten, but was also employed at the time as a synonym for manga or manga film. Although the term “manga film” was already in use, such films were generally referred to as Dekobo, and were considered to be a genre clearly distinct from live-action films.

In 1917, SHIMOKAWA Oten’s Dekobo Shingacho: Imosuke Inoshishigari no Maki (Imosuke’s wild boar hunting), which is said to be Japan’s first animated film, KITAYAMA Seitaro’s Saru Kani Kassen (The Battle of the Monkey and the Crab), and KOUCHI Junichi’s Hanawa Hekonai Meito no Maki: Namakura Gatana (The Dull Sword) 2 were released in rapid succession. Of these titles, only Namakura Gatana is still partially extant, but it is not marked as a “manga film” in the title.

In terms of short films produced in the 1920s, various annotations such as 「線画」(sen ga or line drawing), 「漫畫」(manga), 3 「まんが劇」(manga geki or manga drama), and the like are included before the main title. In essence, they are asserting a distinction from live-action films, but the nomenclature is not unified.

According to The History of Japanese Animation, in 1921, the film classification under the Ministry of Education’s recommended film system included feature films, documentary films, and manga or line-drawing films. Regarding the difference between “manga” and “line-drawing,” it was explained as “a manga film was an animated film based on a story with a so-called narrative, while a line-drawing film was a film that showed moving lines depicting illustrations of mechanical structures or the internal structures of animals or plants.” 4

However, these distinctions in terminology do not seem to have been widely accepted by the general public, and there seems to have been no active effort on the part of the producers to unify the terminology. This is because “manga films” and “line drawings” were both treated in a discriminatory manner as adjuncts to narrative films, and also because the number of productions was small and the technical standards and production processes varied widely. In fact, it may have been more convenient from the standpoint of promoting and selling these films to appeal to the originality of the works by naming them in this fashion, rather than to have them lumped into a single category by standardizing the terminology.

As was mentioned above, the term “animation” in Japan is flexible and ambiguous, even when it is traced back to its starting point, and this trend has continued ever since.

In 1925, YAMAMOTO Sanae, who later became involved in the founding of Toei Doga (Toei Animation), established Yamamoto Mangaeiga Seisakusho. Although the company name includes the words “manga eiga,” the subtitles of the films it produced included terms such as 「教育線画」(kyoiku sen ga or educational line drawing) and 「線畫」(sen ga or line drawing). 5

In 1926, OFUJI Noburo established Jiyu Eiga Kenkyusho (later renamed Chiyogami Eigasha). OFUJI produced many paper-cutout animation works using chiyogami paper and referred to them as “chiyogami eiga” (colored paper films). He is thought to have done this in an attempt to differentiate his films technically from manga and line drawings and to assert his originality.

In the 1930s, short film production became more active, with the establishment of Oishi Senga Seisakusho (later renamed Oishi Kosai Eigasha) by OISHI Iku (Ikuo) and Masaoka Eiga Seisakusho (later renamed Masaoka Eiga Bijutsu Kenkyusho) by MASAOKA Kenzo.

In 1937, a documentary film entitled The Making of a Color Animation 6 was produced to record the production process of OFUJI Noburo’s cel animation Princess Katsura (The Wigged Princess). Although the coloring was done using the cel animation technique in color, the film is referred to as a “color manga.”

In the same year, MASAOKA established the Japan Animation Society in Kyoto. The term “doga” (moving image) was promoted as a Japanese translation of the word “animation.” Although line drawings continued to be produced, it is believed that the increasing number of productions gradually overshadowed line drawings in favor of manga and doga. However, these terms are thought to have primarily targeted animations where drawings or cutouts create movement. It is unclear whether they were also expansively applied to works using stop-motion and other techniques that involve moving three-dimensional objects.

In the 1940s, the situation changed dramatically.

In 1941, the cutting-edge film critic IMAMURA Taihei authored the book Manga eiga ron (Manga film theory) (Daiichi Geibunsha). Although his primary topic of discussion was Disney, he also discussed the situation in Japan and various countries, categorizing them under the general term “cartoon film.” With only a limited print run of 1,000 copies, it seems unlikely that IMAMURA’s writings gained widespread popularity. Nevertheless, he praised manga (cartoon) films as an artistic genre on par with live-action films, even suggesting the potential for future mass production. However, perhaps due to insufficient information, there were many misunderstandings in the interpretation of the production process that included many misconceptions (such as the fact that animation was merely a copy of live-action due to the advancement in animation techniques).

On the other hand, a significant number of creators were mobilized during World War II, and the situation underwent drastic changes with an increase in commissioned works from the navy for the purpose of boosting morale, particularly for those who had avoided mobilization.

In 1942, Momotaro no Umiwashi (Momotaro’s sea eagles) was produced by Geijutsu Eigasha under the auspices of the Japanese Naval Ministry. In the following year, 1943, this film was released as a “feature-length manga” (actually, it was a medium-length film of 37 minutes). In 1945, Japan’s first animated feature-length film, Momotaro: Sacred Sailors, was released, and its advertising officially proclaimed it as a “feature-length war manga film.” Momotaro: Sacred Sailors and MASAOKA’s masterpiece The Spider and The Tulip (1943) were produced by Shochiku Doga Kenkyusho.

In October 1945, immediately after Japan’s defeat in the war, a large group of struggling individual artists banded together to form Shin Nihon Dogasha, which a month later was renamed Nihon Mangaeiga Corp. with even more participants. The core members included YAMAMOTO Sanae, MASAOKA Kenzo, MURATA Yasushi, who is known for his paper cutout animations, and ARAI Wagoro, a pioneer of silhouette animations, but the company disbanded after about two years.

In 1948, MASAOKA, YAMAMOTO, and several others founded Nihon Dogasha to make a fresh start. Both the company name and the artists went back and forth between doga and manga, before eventually settling on doga. However, due to financial difficulties, MASAOKA abandoned the production and left the field.

In 1952, Nihon Dogasha changed its name to Nichido Eiga. Then in 1956, Toei acquired Nichido and welcomed its staff into the core of a brand-new company, Toei Doga. The members included YAMAMOTO Sanae, MASAOKA’s close friend; MORI Yasuji, an animator who looked up to MASAOKA as a mentor; DAIKUHARA Akira, a self-taught animator who perfected his skills under OISHI Iku (Ikuo)’s pupil ASHIDA Iwao; and YABUSHITA Taiji, a producer. After going through a process of differentiation and elimination in the immediate postwar period, it can be said that the main forces behind Japanese manga films were finally consolidated and concentrated here.

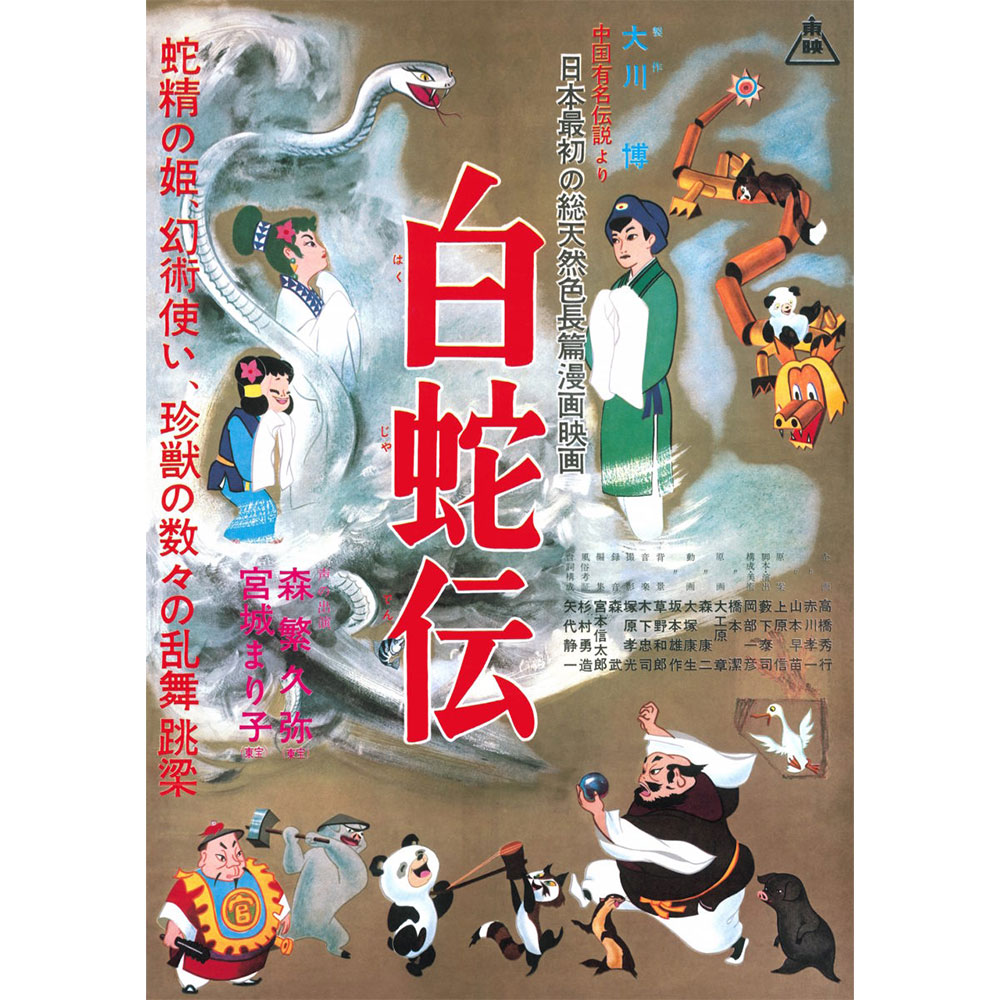

In 1958, Japan’s first color feature-length animation Hakujaden (The White Snake Enchantress), produced by Toei Doga, was released with promotional posters and other materials labeling it as a “full natural color full-length manga film.” Although the term “animation” was used in Toei’s in-house pamphlets, by this time, the term “manga film” was being almost universally used in introductory articles and reviews in newspapers and magazines. 7

From then on, until the 1970s, Toei Doga produced one new feature-length film almost every year. Although the promotional phrases for the individual films varied, such as a “full natural color large scale feature-length manga” or a “color feature-length manga,” the term “manga film” became firmly established as a film genre that was gaining social recognition. At that time, movie theaters primarily showed feature-length films, with short films serving as supplements. On the other hand, the term “doga” was used in the names of production companies, and the concurrent use of “manga film” and “doga” continued thereafter.

By the end of the 1970s, the terms “manga film” and “doga” became less common, and from then until the present, the use of the new term “anime” as an abbreviation has become widespread. The arrival of a social boom, the formation of a fan base among young people, and the successive launch of “anime magazines” coincided, contributing to a rapid spread, along with the revitalization of terminologies. However, in some cases, the words “animation” and “anime” are used interchangeably as the same meaning (with the latter serving merely as an abbreviation of the former), and in other cases to mean different meanings (with the latter referring to a part of the former), with the result that the boundaries between the two words remain as vague as ever.

Some studios continue to use “doga” in their company name (such as Doga Kobo, Kamikaze Douga, etc.), but in other cases, such as Toei Animation, they have switched their company name from “doga” to “animation.”

The above is a brief history, but the terms “senga,” “manga,” “doga,” and others for “animation” have always fluctuated. It is speculated that the terminology stabilized essentially as “manga films” from the 1950s to the 1970s, spanning a quarter of a century. This period coincided with the founding of Toei Doga and its early feature-length productions. In this paper, I propose to regard this as the golden age of manga films, and to adopt the characteristics of the many feature-length films produced in the latter half of that period as criteria for identifying manga films.

The biggest driving force of the golden age of manga films was Toei Doga’s cel-animated feature-length films, which were released at a rate of one per year beginning with Hakujaden in 1958. Naturally, feature-length films are not comparable to short films in terms of their budget, scale of production, scale of release, or social repercussions.

YABUSHITA Taiji, who served as a producer of feature-length films in the early period, wrote the following in “Manga eiga to sono gijutsu” (Manga films and their techniques) (in Eiga Koza 4: Eiga no Gijutsu [Film Course 4: Film Technology] ed. SHIMAZAKI Kiyohiko, Mikasa Shobo, 1954).

In Japan today, almost all manga films are produced primarily with educational expectations in mind, so their planning begins with good intentions toward young boys.

SHIMAZAKI Kiyohiko (ed.), Eiga Koza 4: Eiga no Gijutsu, Mikasa Shobo, 1954, p. 203

To sum it up in one sentence, the understanding was that “the premise of producing manga films is that they should be wholesome films that feature young boys and girls as the main characters.” It is clear that the early Toei Doga staff adhered to this production motive (even though their films were commercial rather than educational films). The original story of Hakujaden is a Chinese folk tale about a white snake who is vanquished by a priest, but the film focuses on a tragic love story with a gentler ending that leads to reconciliation. According to the credits, only two animators, MORI Yasuji and DAIKUHARA Akira, were in charge of original drawings for Hakujaden, although OTSUKA Yasuo, NAKAMURA Kazuko, and KUSUBE Daikichiro also worked on the latter half of the film. Despite being such a small team, their good intentions and enthusiasm were overflowing in each and every scene, making this title a major achievement of manga film.

MIYAZAKI Hayao, who was an aspiring manga artist at the time, was in the middle of his university entrance exams when he first watched Hakujaden. That was the beginning of it all for him.

MIYAZAKI later wrote wistfully about his memories of those days.

At that immature moment in my life, the encounter with Hakujaden left a strong impact on me.

“Koza: Nihon Eiga 7,” Nihon Eiga no Genzai, Iwanami Shoten, 1988, p. 147

It made me aware of my own foolishness in aspiring to be a manga artist and attempting to draw even the absurdist dramas that were popular at the time. Despite the words of disbelief that I uttered, I realized that I was genuinely attracted to the cheap but earnest and pure world of those three-penny melodramas. I could no longer deny that there was a part of me that strongly wished to affirm that world.

From that time on, it seems I have begun to seriously contemplate what I should create. At the very least, I had to do it in a way that was true to my heart, even if it might be embarrassing.

When I saw Hakujaden, it was like scales fell from my eyes, and I realized that I should depict something sincere and generous, like a child. However, parents, as it turns out, can sometimes trample on the purity and generosity of their children. Therefore, I wanted to send out works that said to children, “Don’t let your parents eat you alive.” (…) That starting point is still continuing today, 20 years later.

“My Origins,” lecture organized by Animation Kenkyu Rengokai, 1982, Nausicaa GUIDEBOOK, Tokuma Shoten, 1984, p. 173

MIYAZAKI joined Toei Doga in 1963. It is natural to assume that he was influenced ideologically and technically by his predecessors, who worked on their productions driven by the aforementioned motives. MIYAZAKI mastered basic techniques and honed his skills while working on Toei’s feature films until he left the company in 1972. This decade marked truly the golden age and a period of maturity for manga films.

MIYAZAKI also made the following statement several years later, before the construction of Studio Ghibli’s company building (currently Studio 1) began.

Even if I (we) try to make works for different age groups, the main focus remains on making fun films for children. (…) I want us to depict the reality of children in Japan today, including their wishes, and I want us to make films that they will truly enjoy. I believe we must never forget our fundamental position. If we forget that, I think this studio will perish.

Animage, May 1991 issue, p. 93.

Since the founding of Studio Ghibli in 1985, the characters and settings of MIYAZAKI’s directed films have undergone many changes, but at the root of the production process, MIYAZAKI must have adhered to the motives that YABUSHITA described earlier. In other words, his original intentions remained the same.

Toei Doga’s animation was founded by two strikingly contrasting animators, MORI Yasuji and DAIKUHARA Akira. In a nutshell, Toei Doga’s early manga films were made possible by the amplitude of the expressive styles of these two artists. At the time of the company’s founding, the in-house animators were divided into two factions, even in their private lives, and their subsequent artistic expressions branched out in different directions due to their respective derivations and heritages.

It is well known that MIYAZAKI Hayao respected MORI Yasuji. MIYAZAKI, along with his labor union comrades, belonged to a group that coalesced around MORI as the animation director. MORI, who recognized MIYAZAKI’s talent from an early stage, later wrote that MIYAZAKI “was a figure whose appearance made me want to say, ‘Gentlemen, take off your hats!’” 8

The adorable girls and animals depicted by MORI have a sense of three-dimensional consistency and perfected beauty. His delicate, slow-tempo theatricality was admired not only by MIYAZAKI but also by many of his successors. It is a naturalistic and precise animation, so to speak, that does not depend on wide spaces or stage sets, but instead focuses the audience’s gaze on the performance of the designed characters. MORI’s drawings possess a sense of nobility that embodies the aforementioned “good intentions toward young boys.” For MIYAZAKI, MORI’s approach to drawing and expression of characters seems to have set a standard.

I can hardly say that I was a good disciple of MORI Yasuji. Even as a newcomer, I was aggressive, overbearing and arrogant. I saw Mr. MORI’s work as old-fashioned. Oddly enough, however, I used to assume that Mr. MORI was the most understanding person in the world and I was sure he would support me whenever I tried something new. (…) Mr. MORI was truly generous to me.

MIYAZAKI Hayao, “Short Words,” MORI Yasuji, MORI Yasuji no Sekai (The World of MORI Yasuji), Nibariki, 1992

(…) We received something from Mr. MORI. Like in a relay, may the baton be passed on to the next people…

MIYAZAKI Hayao, Shuppatsuten 1979–1996 (Starting Point 1979–1996), Tokuma Shoten, 1996, pp. 246–247.

DAIKUHARA, on the other hand, excelled at expressionistic and bold animation. His character designs changed with each film, almost as if he were a different person, and included bizarre contortions and distortions.

Fast-paced action and extravagant stage movements are essential to the spectacle of a feature-length film. DAIKUHARA employed a succession of improvisational performances, such as comical and unique poses of characters and the exaggerated slowness or quickness of gestures, demonstrating an originality that at times destroyed the progress of the original story and script. Also, in order to allow the characters to move around in all directions, the design of a large “space” was indispensable.

According to DAIKUHARA, his mentor, ASHIDA Iwao, changed his style for each new production and engaged in a nonchalant approach to creating works. DAIKUHARA himself was influenced by this, resulting in his pursuit of “eye-catching and entertaining performances,” “eccentric settings and stage backdrops,” and “drawing techniques that allow for producing a large quantity faster than others.” MIYAZAKI’s conceptual approach to space, performance, and processing speed are in fact, quite similar to DAIKUHARA’s. However, MIYAZAKI himself has never talked about the influence of DAIKUHARA, and there are no critiques pointing out such an influence. Why is that? There are essentially two reasons.

First, DAIKUHARA, who was by nature adroit and prolific, was not obsessive about taking the time to work out the consistency of scenes, cuts, and performances. Some of his peculiar characters were also unpopular among his juniors. After the original, feature-length films faded away and the abbreviation technique of the original manga-driven TV series became the norm, DAIKUHARA was unable to adapt to this trend and demonstrate his strengths, and so he withdrew from the forefront. For younger filmmakers like MIYAZAKI, who were aiming for higher forms of expression, DAIKUHARA was excluded from the early stage of learning.

Second, in their early years, MIYAZAKI and his colleagues were guided by a man who had refined DAIKUHARA and MORI’s drawing methods, put them into practice in subsequent works, and tirelessly and methodically passed them on to future generations of artists. That man was OTSUKA Yasuo.

OTSUKA independently translated into Japanese and copied Preston BLAIR’s Animation: Learn How to Draw Animated Cartoons (1949), a textbook on the fundamentals of Disney’s drawing techniques, and applied them practically to the scenes he worked on. 9 OTSUKA was a rare animator who learned from all precedents of good drawing, and strove to absorb and integrate them. For most young animators, DAIKUHARA, who improvised and changed his style, and MORI, who maintained an unchanging style, were figures to look up to in the distance. In contrast, OTSUKA was more of a “big brother” that they could talk with. 10 As a result, OTSUKA can be regarded as an ideologue of the animators who gathered at the Toei Doga in the early days.

One could say that MIYAZAKI indirectly benefited from DAIKUHARA’s technology through OTSUKA.

The space designed by MIYAZAKI Hayao is filled with a variety of gimmicks, and the vertical stage that busily moves up and down is extremely attractive. Once again, let us quote MIYAZAKI’s own words.

For me, what is truly interesting about manga films is that they create a world, use up all of its space, and end with a conclusion, which makes them extremely enjoyable to watch and motivates me to do my best. The concept of manga films is a lie. Because it’s a lie, it would be nice if there’s a big lie, but also a little bit of truth mixed in. That’s what I hope for.

Mata aeta ne! (I met you again), pp. 151–152

The vertical stages designed by MIYAZAKI include Lucifer’s Castle in The Wonderful World of Puss ‘n Boots (1969), designed by art director TSUCHIDA Isamu; the pirate ships Pork Sautee and Gratin in Animal Treasure Island (1971); the triangular tower in Future Boy Conan (1978); Cagliostro Castle in Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979); the interior of Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986); and the bathhouse Aburaya in Spirited Away (2001), to name just a few. Each of these stages is a closed room isolated from the outside world, and the stage itself is closely connected to the story. The characters busily moving about in these places are funny and endearing all the more because they are working so hard.

I do not believe that these things were built up single-handedly, but rather that they are the result of summarizing and condensing successful examples of earlier works. I would like to trace the source of these successes.

In the middle of The Castle of Cagliostro, LUPIN climbs the steep blue triangular roof to rescue Clarice, who is imprisoned in the north tower. The composition, viewed obliquely from above, emphasizes the height and danger of the scene, leaving the viewer with a strong impression. It is well known that the screen design before and after this scene closely resembles the upper floors of the kingdom of Takicardie in Paul GRIMAULT’s La Bergère et le Ramoneur (The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep) (1952). The castles in which the two films are set also have in common that their upper and lower floors are connected by a long series of exterior staircases. GRIMAULT directs his films as ensemble dramas that do not involve any particular character, and the overall situation is portrayed objectively. MIYAZAKI’s direction, on the other hand, is designed primarily to stay close to LUPIN, and even though the superficial illustrations are similar, the impression one gets from the scenes is quite different.

Actually, the source of this scene may be traced back to the training scene in Toei Doga’s second feature film, Magic Boy (1959). The overhead view of the scene where the boy Sasuke climbs the high cliff of Mount Togakushi, and the layout of the scene that shows him nimbly crossing the distant rugged mountains as if they were stepping stones are very similar to scenes in The Castle of Cagliostro. Moreover, the direction of Magic Boy is also focused largely on the main character.

DAIKUHARA Akira was in charge of directing this production (the credits identify him as the co-director along with YABUSHITA Taiji, but it appears that DAIKUHARA was mainly responsible for the scene design). DAIKUHARA often employed vertical spaces that developed upwards and downwards, and deep spaces that extended from the foreground to the background, and he frequently used action to move around within the space.

The second half of the feature-length film Doggie March (1963), for which DAIKUHARA was the animation director, is set on a roller coaster and includes the danger of falling from a great height and the terror of the approaching coaster. This scene is similar to the scene in the first half of Castle in the Sky, in which a light railway chase through the Slug Valley culminates in a fall to the bottom of the valley. Doggie March was the first film for which MIYAZAKI was in charge of animation after he joined Toei Doga, so it is conceivable that he may have undergone some kind of imprinting.

OTSUKA Yasuo participated in the founding of Toei Doga as an animator. He received guidance from MORI’s group for the short film Koneko no Rakugaki (Kitten’s Scribbling) (1957) and from the DAIKUHARA group for the feature film Hakujaden (1957). OTSUKA was officially promoted to the role of original illustrator for Magic Boy, and he developed the overhead or bird’s-eye viewing angle that DAIKUHARA attempted in that film and in many of his subsequent works.

Around the same time, OTSUKA asked YABUSHITA Taiji, who directed Hakujaden, “Is there any particular reason why the main characters in Hakujaden often move from the right hand to the left hand of the screen and why complex compositions such as overhead views are not used?” In response, YABUSHITA said, “I think it is influenced by the conventions of stage performances such as plays and kabuki. Also, many animators are right-handed, so it is easier to draw left-facing faces. I try to avoid using a bird’s-eye view or extremely tilted poses, as they often result in the characters collapsing or striking unnatural poses. Not only that, but the audience for animated films mainly consists of young children, so we have to avoid making the visuals too complicated for them to keep up with.” 11

OTSUKA probably had some doubts about whether it would be acceptable to create more complex and sophisticated screen productions and productions that were intended for adult audiences. I believe that this awareness of these issues was extremely important to the development of manga films.

In the final duel scene between Goku and Gyu-Mao (Bull Demon King) in his third feature-length film, Alakazam the Great (1960), OTSUKA raises the camera to a higher elevation to create an overhead view as if shot from the air. (He also introduced the Disney-style “stretch and squash” exaggeration techniques in the same scene). In his sixth feature film, The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963), together with TSUKIOKA Sadao, he introduced a series of innovative spatial compositions, such as a tilt-shift view to look up from directly below, and camera work that moves at high speed into the depths of the scene as if crawling along a cliff. The resultant vibrant and ever-changing drawings captivated not only young children but also teenagers, with the result that the age range of the audience expanded. The composition of the screen and the construction of the stage, with differences in height, had a far-reaching influence on subsequent animations.

In the latter half of The Wonderful World of Puss ‘n Boots, OTSUKA was in charge of the scene in which the demon king Lucifer, transformed into a three-headed dragon, chases the main protagonists Pierre and Pero from the bottom of the stairs. Immediately afterwards, Pierre and his friend, who have escaped to the drawbridge on the upper floor, and Lucifer’s “up and down” control of the opening and closing of the bridge are interlinked. The story is beautifully connected to the vertical space of the closed room, and the difference in height instantly conveys to the audience the sense of inferiority and danger experienced by the two. This is a scene that OTSUKA was amused by the stage designed by MIYAZAKI and inflated and completed with considerable skill. MIYAZAKI’s concept of utilizing differences in elevation became a recurring theme in his later films, starting with this work. It is believed that OTSUKA’s contribution, inheriting DAIKUHARA’s spontaneity and pioneering spirit and combining it with MORI’s design philosophy, played a significant role in elevating it to a higher level.

Accordingly, it is extremely important to note that OTSUKA Yasuo was the animation director of Future Boy Conan and The Castle of Cagliostro, which represent the pinnacle of manga films directed by MIYAZAKI. MIYAZAKI’s works are infused with elements inherited from OTSUKA as well as his own unique developments of OTSUKA’s techniques.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, there have been two major events featuring manga films, namely the special screening program Hayao Miyazaki: Genealogy of His Manga Films 1963–2001, held at the Hall of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum from June to July 2001, and the exhibition Japanese Animated Films: A Complete View from Their Birth to “Spirited Away” and Beyond, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo from July to August 2004. Both exhibitions were supervised by OTSUKA Yasuo.

Going back in time, OTSUKA’s teacher was DAIKUHARA Akira, DAIKUHARA’s teacher was ASHIDA Iwao, and ASHIDA’s teacher was OISHI Ikuo. Needless to say, MORI Yasuji’s teacher was MASAOKA Kenzo. Coincidentally, the genes of OISHI and MASAOKA, who represent two contrasting currents of postwar manga films, live on in MIYAZAKI.

Two of MIYAZAKI’s past films were labeled as manga films in their promotion.

For Castle in the Sky (1992), MIYAZAKI wrote on the poster the catchphrase, “A delightful manga film that will make your blood boil and your flesh pound.” For Porco Rosso (1992), MIYAZAKI himself wrote in his “Notes on Directing” that the film was “a manga film for middle-aged men whose brain cells have turned to tofu due to exhaustion.” MIYAZAKI expressed a sense of guilt, saying, “Porco Rosso should have been made for children.” However, even though it was aimed at a middle-aged audience, it did not lose its good intentions and optimism, and it was broadly popular with children as well.

As the analog world turned to digital around the turn of the century, the realm of expression in animation expanded, making it possible for individual depictions to become even more elaborate. Nevertheless, one of the reasons why MIYAZAKI’s works remain unrivaled and stand alone in their own right is that they are rooted in his commitment to hand-drawn expression and the classic ambition of the manga film, which has good intentions at its core.

In his later years, DAIKUHARA repeatedly told the author as follows.

“If you want to show the fun of the story, live action is fine. But doga should show things that only doga can show. The doga movies that I think are the most interesting are those produced by Miya-san (MIYAZAKI Hayao). The design of the old woman with the big head (Yubaba from Spirited Away) grabs everyone’s attention at first sight. The cut in which she is looming toward the audience is also very good. I also like the strange castle that looks like a mish-mash and moves around (in Howl’s Moving Castle [2004]). Fantastic things always behave in unexpected ways. That’s what really makes doga so much fun.”

DAIKUHARA recognized MIYAZAKI as the heir to the techniques and the technical philosophy he had created, and so he supported him from the shadows.

MIYAZAKI’s latest film, The Boy and the Heron (2023), which is now on release, is set in a vertically closed room, and has the aforementioned good intentions toward young boys at its core. At first glance, the development of the story, which is told in a dazzling chain of images, may seem difficult to understand, but it follows the universal “tale of going and returning,” and the gist of the story is clear. It is rather manga-film-like in that it prioritizes the pursuit of “improvisational fun” over the consistency of the story and the connections between scenes. However, the film’s multilayered scattering of abstract allegory makes it difficult to describe it as merely a work of entertainment; it seems to be more like a kind of evolution or mutation.

The main setting of The Boy and the Heron is “the fourth year of the war” (1945), and the main character, a boy named Mahito, is 11 years old (he was born in 1934 or 1933). The pamphlet describes the film as an “autobiographical fantasy,” but MIYAZAKI, who was born in 1941, must have still been a toddler at that time. Mahito is actually closer to the age of OTSUKA, who was born in 1931. This is where I can sense MIYAZAKI’s admiration and respect for the generation that came before him.

To put it another way, the careful depiction of daily life in the first half of the film is in the style of MORI Yasuji, while the strange characters in the second half are reminiscent of DAIKUHARA Akira, and the blue heron man who moves between the two worlds is a kind of comedy relief in the style of OTSUKA Yasuo. In addition, the bipedal anthropomorphic birds also have a manga film-like design.

MORI passed away in 1992, DAIKUHARA in 2012, and OTSUKA in 2021. If they were still alive, all three would have greatly enjoyed watching The Boy and the Heron.

MIYAZAKI made the following comments over 40 years ago.

I have this feeling that we are not merely adapting the techniques and methods thought up by our predecessors, who pioneered the world of manga films, to create their own world. Despite the challenging economic conditions, with theaters hardly functioning as a market, we don’t want to give up. … When a boy who watches a film comes home, he seems stunned and doesn’t utter a word. It’s as if he can’t speak to others due to the preciousness of the experience. Stirred by a longing almost enough to make him cry… I want to make that kind of manga film someday…

Mata aeta-ne! (I met you again), pp. 152–153

MIYAZAKI has continued to energetically direct outstanding feature-length films for theaters, breaking Japan’s film box office records, demonstrating the fundamental potential of manga films, and even reshaping the market’s power structure. This work, completed after the first-ever seven-year-long production, may have been the fulfillment of a long-held dream. In recent years, MIYAZAKI has repeatedly described his films as descendants of “popular culture,” 12 and it seems that he considers manga films to be one of the components of this culture.

It is my hope that the baton of manga films, the yarn of popular culture spun by the now 82-year-old MIYAZAKI with all his might, will be passed on to the next generation who will carry the mantle of Japanese animation.

notes

*URL links were confirmed on August 29, 2023.