MIYAMOTO Yuko

Animated film The Colors Within, released at the end of August 2024, is the latest work by the young visionary director YAMADA Naoko, known for creating fresh, youthful animations since K-ON! that aired on television in 2009. This article focuses on the film’s color scheme, exploring its role in animation expression, the protagonists’ emotional journey, and the overarching themes YAMADA weaves in her works.

Synesthesia is a phenomenon in which elements perceived through the five senses, such as sight, hearing, smell, and touch, are accompanied by additional sensory experiences from another sensory pathway. This can include things like letters being perceived as having colors, or seeing shapes when hearing sounds. There is also a form of synesthesia where time is perceived visually.

The theory that poets like Arthur RIMBAUD and MIYAZAWA Kenji may have been synesthetes is well-known. Similarly, in the history of animation, it is said that Oskar FISCHINGER and Norman MCLAREN were also synesthetes. FISCHINGER’s animations feature abstract shapes that move in sync with classical music. This is often considered the origin of what is now called motion graphics. FISCHINGER’s work also influenced Walt DISNEY, leading to the creation of Fantasia in 1940.

Filmmakers like Hans RICHTER and Viking EGGELING, who came before FISCHINGER and were associated with the “absolute film” movement during the silent film era, had already experimented with combining abstract shapes and music. Looking further back, abstract art in the early 20th century itself was a pursuit of synesthetic experiences. In this way, the history of art and synesthesia has permeated the history of animation.

When discussing this topic in animation history lectures, I sometimes come across students who share their own experiences with synesthesia. Some even didn’t realize that their sensory experiences had a name until they took the class. Synesthesia comes in all shapes and sizes—one student shared that they see numbers as having colors, so doing calculations becomes extremely difficult. With additions for example, the mixed color from adding up the numbers does not match the color of the sum, causing a lot of confusion.

It never occurred to me that such difficulties would come with synesthesia until I heard stories from them. These make us increasingly aware of the reality that we all have unique ways of seeing the world. Beyond the assumption that the diversity among individuals can be explained and interpreted simply by understanding that each person perceives the world through the unique context of their own life, and that we have varying perspectives, there is an essential difference that lies between oneself and others on the dimension of how the world itself is perceived. That realization presents a daunting sense of bewilderment.

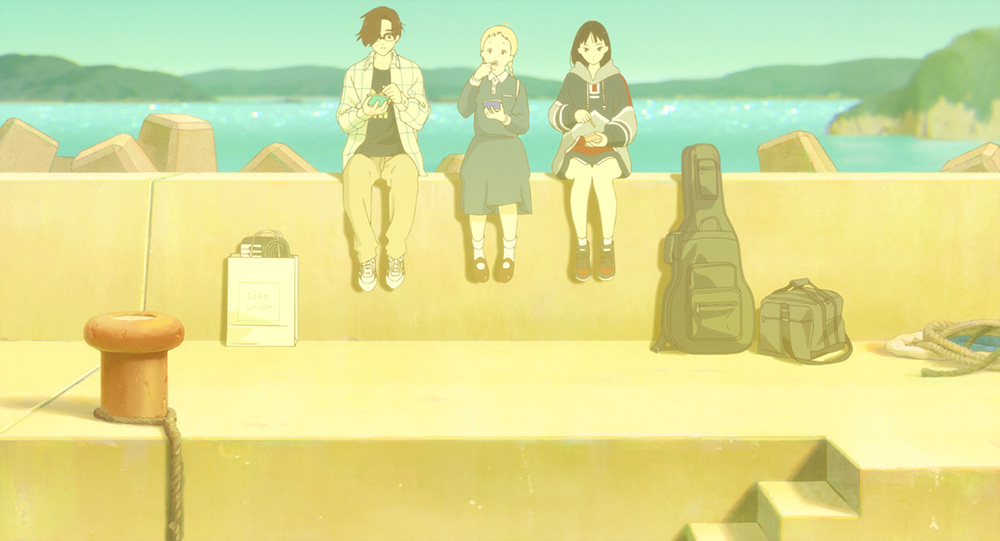

In YAMADA Naoko’s The Colors Within (2024), the protagonist, Totsuko, can be described as a synesthete in this context. She perceives the world in colors different from what others see and fears being judged as an oddball if she reveals what she perceives. Totsuko forms a band with Rui and Kimi, both of whom harbor their own secrets and the loneliness that comes with it. Together, they perform at the school festival before bidding Rui farewell as he leaves for university. True to YAMADA’s style of depicting “a slice of life” that is ordinary and drama-free, as seen in the K-On! series, this film does not rely on an extreme “end-of-the-world” type of narrative. Instead, it carefully portrays the seemingly mundane moments of daily life that, while they may appear uneventful, are actually meaningful and special. The way the characters work together, each carrying their own secrets, and sharing a mutual “love” to connect—even for a brief moment—illustrates something truly extraordinary, a miracle even, especially given the stark differences between individuals.

Many commercial animations in Japan produced with digital technology today still echo the conventions of cel animation. However, since cel as a material is no longer used, they are now referred to as having a “cel animation look.” One of the key features of traditional cel animation is the clear outlines that define the characters. The process of drawing the outlines and coloring them in remains largely unchanged, even with the shift to digital production. It has also become increasingly common to see 3DCGI animation that captures this cel animation look. What remains crucial, however, is the simulation and implementation of the outlines, which are not inherently part of 3DCGI.

“Anime” is thus often characterized by its use of outlines. The Colors Within is no exception, but there are several memorable images in the film where the outlines are less defined and appear blurred. When Totsuko composes music, she feels that the colors of the music resemble the colors of Kimi and Rui. The colors Totsuko perceives are like watercolor droplets on a white sheet of paper, without defined outlines. Looking back at a drawing from her childhood, it depicts blobs of watercolor that vaguely resemble human forms, but the figure lacks an outline. The colors that Totsuko sees are likely without outlines in this way. Totsuko’s drawings evoke a scene midway through Ryan LARKIN’s Walking (1968), in which multiple figures walking are animated using various watercolor hues.

The gradual transition from color to scenes with more defined outlines is remarkable. For instance, at the secondhand bookstore Shironekodo, when Kimi gives her approval for Totsuko to form a band, the next shot captures her reaction as if she were struck by lightning. A deep blue color, set against a white backdrop, is painted almost horizontally with texture. These blurry blocks of color gradually dissolve into mountains seen from a boat, transforming into a detailed view seen from the ship Totsuko and Kimi are on. Or the scene where Rui departs by boat towards the end of the film. The white screen initially fills with multiple colors, and the background sky and the partially visible boat slowly dissolve into view, turning into a more defined scene.

In these scenes, colors and textures are depicted before a subject is given meaning through defined outlines—it later transforms into a representation of an object that points to a specific scene. Colors without any boundaries come first, and only afterward is it identified as an “object” with meaning and function within the scene. This way of expression with soft colors devoid of outlines gradually taking shape evokes a metaphorical connection to the simple yet fundamental relationship with the world, where one perceives the world not through imposed boundaries, but through the very essence of its qualities. The way Totsuko perceives the world is clearly different from a non-synesthete, but before identifying something through the lenses of meaning—such as its attributes, social status, or usefulness—don’t people first perceive it as it is? When YAMADA Naoko intricately depicts everyday life, the film resonates on an emotional level because her expression seeks to touch upon the source of this very connection to the world. The expression of color without outlines not only characterizes this film but also seems to be linked symbolically to the core of YAMADA’s creative style. Totsuko perceives people through color. What she receives from others is color, not the outlines of their figures. What Totsuko finds beautiful in a person is not their physical form, but the color they emanate. Kimi is likely portrayed as a beautiful girl in line with anime’s visual conventions, but Totsuko’s “infatuation” for her is not based on her physical appearance, but on the colors she radiates.1 YAMADA has previously explored intimate relationships and emotions between women in her works. She seemingly has however avoided explicitly placing these relationships within existing discourses on sexuality and gender, both within and outside of her films. Whether or not the audience agrees with this approach is subjective, but from the context of color and outlines discussed here, the following can be said: Through Totsuko’s perception of the world and her relationships with others, the film portrays a world and relationships that transcend the limitations of pre-existing boundaries or outlines. Totsuko’s world is shaped by her refusal to let go of the state before outlines are defined, or her inability to “change” this.2

The pursuit of synesthesia in abstract art has often been described in relation to music, as music is considered a purely abstract form of art. At the same time, trends in unrealistic or non-representational art in the 19th century, against objectivism with an emphasis on inner and subjective visions such as dreams and hallucinations, led to the emergence of abstract art.3 Paul WELLS emphasizes the “individuality” of animation as an expressive form,4 and the evolution of animation and its works, stemming from this abstract art tradition, provide a better context for this. The Colors Within can be interpreted as a work that bridges abstract art and the history of animation with a central theme of synesthesia explored through a personal perspective and its connection to music.

However, this is a matter of theme and content, rather than purely form. The time shared by the three protagonists is mediated by music, which unites these three distinct individuals. Totsuko’s unique perception of the world cannot directly be conveyed to others, but through the mediation of sound, it allows for a shared experience. What cannot be outlined is expressed through the abstract form of music. In doing so, amidst their “differences,” it becomes possible to perceive the unoutlined, albeit through a different approach.

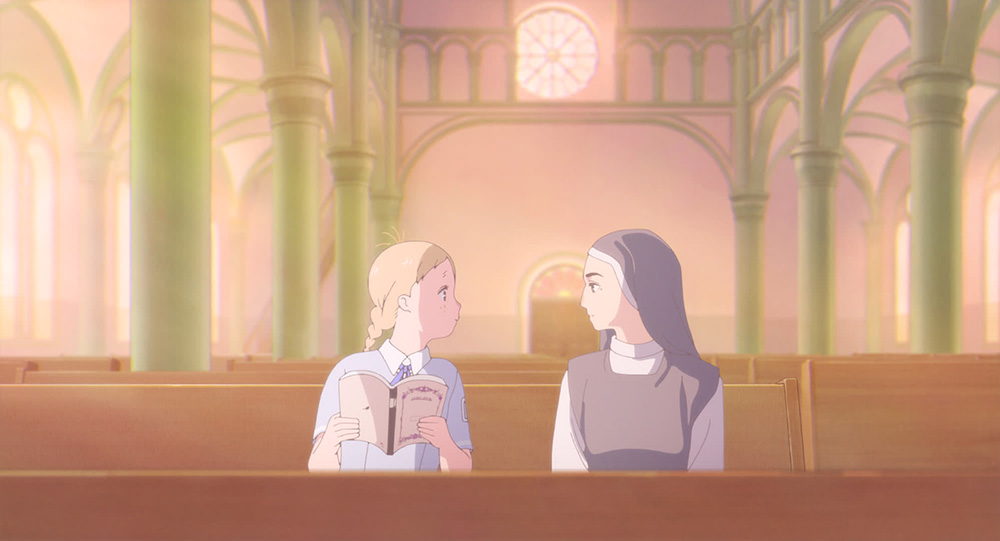

YAMADA’s visual style, which honors the subtlety of daily life, feels, in a way, like a prayer. The act of prayer itself is portrayed in scenes within the film. Totsuko prays for the “acceptance of what cannot be changed.” Initially, she is praying to accept the unique way in which she perceives the world. Acceptance is forgiveness, and prayer is also a plea for forgiveness. Through their interactions, the three protagonists likely uncover what can and cannot be changed within themselves, ultimately arriving at the acceptance of what cannot be changed—essentially forgiving themselves. It is only then that Totsuko sees her own color and comes to understand her true self. Forgiveness and acceptance also mean giving up, and giving up is, at its core, the act of illuminating.

Faced with overwhelming differences, to reveal, accept, and forgive. Through the process of recognizing blurred colors, the fabric of daily life is transformed into a miracle. The personal vision, invisible to the outside world, is partially revealed (or forgiven), forming part of the lineage of abstract art and animation influenced by this process. The Colors Within, however, seems to return these elements to YAMADA’s artistic expression and themes.

At the first screening of this film, the person sitting next to me was in tears midway through. I also watched it at a multiplex on opening day, where I saw two people deeply moved, talking tearfully as they left the theater. I have come across similar scenes to varying degrees with YAMADA’s films. It is often the least unexpected moments in the story that bring out the tears. This film seems to amplify that quality. YAMADA’s vision that celebrates our world is likely experienced collectively by the audience. We, as the audience, briefly share YAMADA’s vision despite our own overwhelming differences, and through the fictional animation, we encounter a world that is yet to be fully outlined. In that moment, we are opened to the true miracle of sharing that presence.

notes

information

The Colors Within

Director: YAMADA Naoko

Screenplay: YOSHIDA Reiko

Music & music director: USHIO Kensuke

Character design & animation director: KOJIMA Takashi

Original character design: Daisuke RICHARD

Cast: SUZUKAWA Sayu, TAKAISHI Akari, KIDO Taisei, YASUKO, YUKI Aoi, KOTOBUKI Minako,

TODA Keiko, etc.

Planning & produced by: STORY Inc.

Production & produced by: Science SARU

Release Date: August 30, 2024

Running time: 1 h. 40 min.

https://kiminoiro.jp/ (in Japanese)

*URL link was confirmed on October 1, 2024.