Gigan YAMAZAKI

From the big boom resulting from its 1966 television broadcast to the present, the Ultraman franchise continues to evolve. This article turns its attention to UCHIYAMA Mamoru, who has worked on many of the comicalizations (comic book adaptations) of the Ultraman series running in parallel to the television show. Including his relationship with the original version, we will explore how he began drawing Ultraman and the developments that have happened since.

Albeit not a term generally used, there is a genre of manga called “comicalization.” It is the manga equivalent of novelization, which is the adaptation of a movie or TV series to a novel. It is not what one would consider a glamorous job. It is mostly done by newcomer manga artists and veteran manga artists past their prime, and in the past, it was rarely published in book format.1 Nevertheless, when works are based on animation or tokusatsu (live-action productions with special effects), it is not uncommon for them to be republished or reevaluated after many years. All the more so if that newcomer later goes on to become a popular artist. In the Ultraman series, prominent examples include Ultra Q (1966), drawn by KAWASAKI Noboru and NAKAJO Ken (under the name NAKAJO Kentaro); Ultraman (1966–1967) by UMEZU Kazuo; Ultraseven (1968) by KUWATA Jiro; and Ultraman Taro (1973) by ISHIKAWA Ken.2 It is only natural that the greater the gap between these examples and the representative works of each artist, the more interested we are in their comicalization works.

Now, as you can see, there are impressively big names in the lineup of artists who comicalized the Ultraman series, but when tokusatsu fans hear the title “master of Ultramanga,” the mangaka that pops into their minds is none other than UCHIYAMA Mamoru.

UCHIYAMA started his career as an animator at Tatsunoko Production, best known for Gatchaman (1972–1974) and the Time Bokan series. While UCHIYAMA first worked in the animation department, he was later brought over to the manga division, where the company’s future third president, KURI Ippei,3 was assigned. He helped with the bodies of characters and backgrounds drawn by KURI. He subsequently made his debut as a manga artist with the release of Che Gebara (Che Guevara) (1968) in Kibo no tomo (Friends of Hope) after receiving a request from Ushio Publishing. But Tatsunoko Production in those days did not permit doing part-time work, so the commission was apparently done without the company knowing. In the end, he seemingly worked with Kibo no tomo for almost half a year while starting on Tatsunoko Production’s comicalizations for publications, including Shogakukan’s educational magazines. Though we still do not have a clear picture of all his works from this period, before long, IKAWA Hiroshi, the editor-in-chief of Shogaku ninensei (Elementary Second Grade), asked him: “Can you draw monsters?.” After drawing one or two pieces while referencing photographs, he was offered a job involving Tsuburaya Productions, renowned for the Ultraman series. That was Janbogu esu (Jumborg Ace).

Janbogu esu (Jumborg Ace) aired in 1973 from January to December, marking Tsuburaya Productions’ 10th anniversary. However, UCHIYAMA’s Janbogu esu manga was serialized in Shogaku ninensei from the 1970 October issue to the March issue of the following year, dating three years before the TV broadcast, which means this work is not a “comicalization.” Anticipating later television adaptations, Tsuburaya Productions had been creating original heroes for Shogakukan’s children’s magazines, and this was one of those works.4 At the time, UCHIYAMA was involved in the comicalization of The Adventures of Hutch, the Honeybee (1970) also for Shogaku ninensei, but was replaced his position as the main artist to work on the serialization of Janbogu Esu.5 The reason for this seems to be that it wasn’t feasible to work on The Adventures of Hutch, the Honeybee (1970) and the serialization of a rival company’s manga at the same time. So, UCHIYAMA left Tatsunoko Production and became an independent manga artist. Then, after Janbogu Esu, he started working on the comicalization of Return of Ultraman,6 which started airing on TV in April 1971. Here, the story of UCHIYAMA and Ultra begins. At this time, the future “master of Ultramanga” was merely one of many comicalization artists. Return of Ultraman artists include MORITO Yoshihiro, who later achieved steadfast success with Mikroman (1974–1985), NAKAJO Kentaro,7 mentioned earlier, and HISAMATSU Fumio, who did Supa jetta (Super Jetter) (1965–1966) and Boken gabotenjima (Adventure on the Gaboten Island) (1967). UCHIYAMA, however, was also illustrating a large amount of Ultraman and monster visuals other than for the manga, such as for the project page and cuts for note and coloring books published by SHOWA NOTE. UCHIYAMA’s style was swiftly established.

One of the most appealing elements of UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga would most likely be the appearance of his Ultra Warriors. The Ultra Warriors are mainly categorized into two types: the Man-type with oval eyes and the Seven-type with hexagonal eyes. The characters can be traced back to the original Ultraman and Ultraseven, respectively. In contrast to the Seven-type, which has a more mechanical and detailed design, the Man-type, which made its appearance in the Showa-era Ultraman series, has a remarkably simple design that makes it difficult to imitate. Even a minor imbalance can easily cause the face to lose its tightness. Of course, there was also the technique of drawing the mask as it appeared on screen, and in his later years, UCHIYAMA started creating Ultramanga with a more realistic touch—an approach only possible in an age with abundant reference materials, including three-dimensional objects. But in those early days, resources were still limited, especially regarding the monsters, of which he would only receive two or three negative films. So, he would draw details like the monster’s back, using his imagination to fill in the blanks. At any rate, the way he drew parts such as the eyes and human-esque mouth, which he recomposed with several relatively straight lines while also being mindful of the suit’s peepholes, influenced many other artists. UCHIYAMA’s spin on the characters, which daringly deformed the elements of the suit without losing its essence, must have seemed quite “cool” to his peers.8 The depictions of the extremely muscular female body shape or the Ultra Warrior’s curved backline have never been mimicked by other artists, but these are also characteristics that make UCHIYAMA’s Ultra truly unique. Designer MURAYAMA Hiroshi, who later became a key figure in the Heisei Ultraman series, also professed that UCHIYAMA had a big impact on him. The eyes and mouth of Ultraman Tiga, designed by MARUYAMA, certainly share a close resemblance to UCHIYAMA’s Ultra Warriors.

As previously mentioned, UCHIYAMA’s history with Ultramanga started when he comicalized Return of Ultraman for Shogaku ninensei. The Shogaku ninensei serialization ran for four years while switching titles to Ultraman Ace (1972–1973), Ultraman Taro (1973–1974), and Ultraman Leo (1974–1975) to match those of the TV series. Furthermore, with Taro also published in Shogaku gonensei (Elementary Fifth Grade), and the following year, Leo in Shogaku sannensei (Elementary Third Year), UCHIYAMA showed a period of frenzied activity. Even more, on top of these regular publications, he also wrote full-length special editions for each magazine while working on comicalizations other than Ultramanga—a truly astounding amount of work. His work did not stop at manga but also included doing illustrations for Taro’s main story in Episode 25, Moero! Ultra 6 Kyodai (Burn! The Six Ultra Brothers), greatly contributing to the series’ worldbuilding. Needless to say, the cloaks worn by the Ultra Brothers,9 now considered the norm, can be traced back to UCHIYAMA’s portrayals in his illustrations and manga.

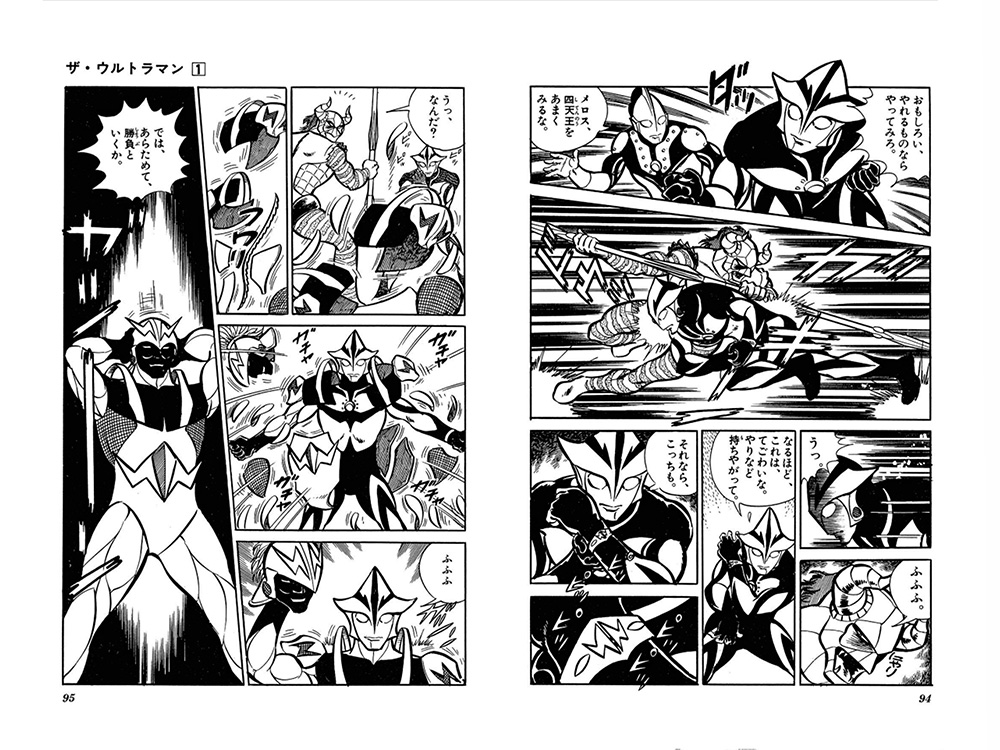

Now, let’s return to the main topic. It is common knowledge to tokusatsu fans that during the Showa period, the Ultraman series was temporarily suspended after Leo. UCHIYAMA’s series in Shogaku sannensei, however, never ended and finally evolved into a full-length original story: The celebrated masterpiece Sayonara Urutora kyodai (Farewell Ultra Brothers) (1975–1976).10 Zetton, Black King, Bullton, Ace Killer…… The Ultra Brothers fall one after the other at the hands of the monsters they are the most susceptible to. The mysteriously revived monsters are incarnations of Uchu dai mao jakkaru (The Great Space Demon King Jackal), who was once exiled to a black hole by Ultraman King. In the end, the Land of Ultra is devastated, but the mysterious armored Ultra Warrior, Melos, appears before the commander of the Inter Galactic Defense Force, Zoffy, who is attempting a comeback with a few survivors. Initially, Melos and Zoffy are at odds, but they soon join hands and challenge Jackal’s army to a final battle. The thing to note from the series is its space opera-like progression, which is far removed from the Ultraman series’ story format, and after this work, UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga also ends temporarily. Yes, “temporarily” is the important part. If it had truly ended here, no matter how good of an artist, UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga would probably have ended up as a cult classic known only by a few devoted fans.

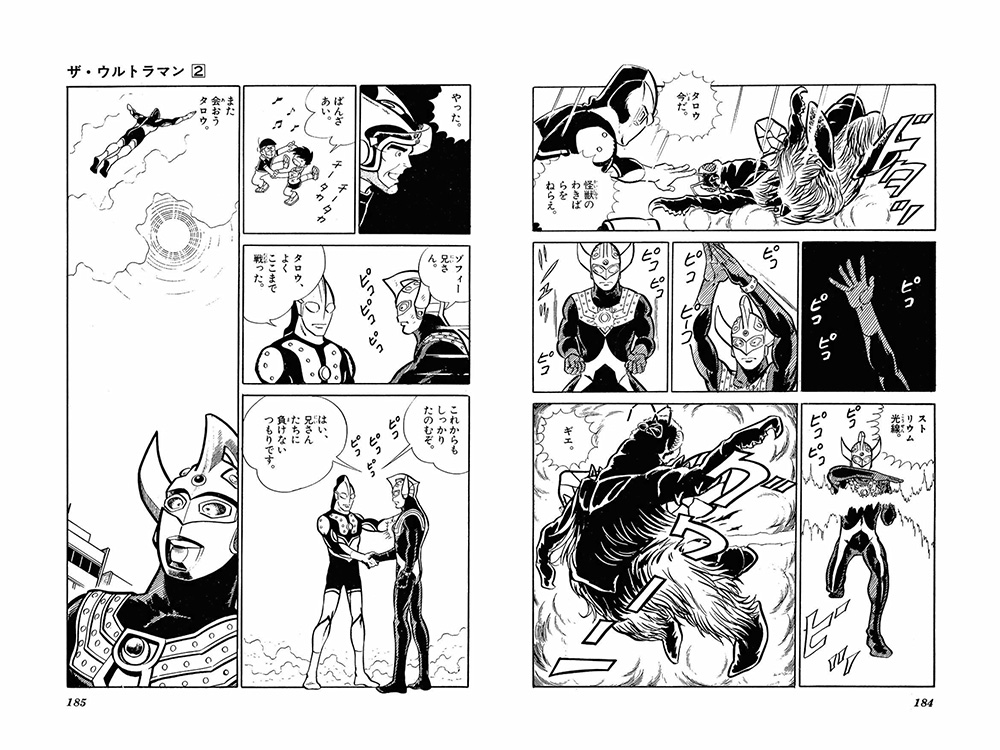

Two years after the serialization of Sayonara Urutora kyodai (Farewell Ultra Brothers), it was retitled Za Urutoraman (The Ultraman) and reprinted in Monthly CoroCoro Comic shortly after its first issue, causing the popularity of UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga to skyrocket. The fact that an extra special edition of CoroCoro Comic (1978) was released during the same time as the reprints of Ace, Taro, Leo, and Sayonara Urutora kyodai, may show just how enthusiastic people were about his works. This, in return, was so popular that it resulted in the release of Korokorokomikku tokubetsu zokan 2-go (CoroCoro Comic Special Extra Issue No. 2) (1978), in which UCHIYAMA created a new spin-off11 alongside the Ultramanga of another artist. Soon after, a new original series—Tobe! Urutora senshi (Fly! Ultra Warriors) (1979)—also started in Shogaku sannensei. The story showed the battle between the Ultra Brothers and formidable unknown enemies set in a “world beyond the universe ≠ Earth” and was very much an extension along the lines of the Sayonara Urutora kyodai world. Although its serialization would last less than a year, UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga was finally published in book format with a total of four volumes nearly seven years after the serialization of Return of Ultraman began. It was called Za Urutoraman urutora kessaku-sen (The Ultraman: Ultra Selected Works), done with Tentomushi Comics. As the title indicates, this was not a comprehensive compilation but rather selected episodes from Ace, Taro, and Leo together with the original stories mentioned above.12 It has become a title transcending time and enjoyed by generations of readers.

After Sayonara Urutora kyodai, UCHIYAMA starts serializing the baseball manga Ritoru kyojin-kun (Little Kyojin-kun) (1977–1986), in which an elementary school student who throws a fastball that puts even professionals to shame joins the Yomiuri Giants team. At first, it was only published in Shogaku ninensei, but it quickly became a hit and was released in several elementary grade magazines and Corocoro Comic at the same time. The last panel in the final issue of the aforementioned Tobe! Urutora senshi (Fly! Ultra Warriors), which he was working on during this time, was accompanied by the words “79.11 THE END.” This was right when UCHIYAMA was expanding his activities to shonen (boys) and seinen (young men) magazines so as not to be limited to only children’s magazines. I presume he felt this would likely be his last Ultramanga and comicalization. But the world of Ultra was still in need of UCHIYAMA’s talent.

The Ultraman series returned after a few years, influenced by the revival boom of the late 1970s to early 1980s, but entered a hiatus again after only releasing The☆Ultraman (1979–1980)13 and Ultraman 80 (1980–1981). Nonetheless, in order to keep publishing the Ultraman series in different magazines, including the elementary grade magazine series, with the support of Tsuburaya Productions, Shogakukan introduced a new armor-wearing hero called Andro Melos.14 It goes without saying that it was based on none other than the abovementioned Melos. His final design ended up having a green mechanical armor, but some of the earlier designs resembled the “first” Melos’s armor with very similar weapons, like lasers on both of his shoulders and an andoran (Andrang) on his abdomen. Zoffy, the eldest brother of the Ultra brothers, also appears in armor as a substitute for Melos himself. This is very revealing of just how big an impact UCHIYAMA’s Melos had made on other creators at the time. Moreover, UCHIYAMA himself also serialized Urutora senshi ginga dai senso (Ultra Warriors: The Great Galactic War) for Shogaku sannensei from the June 1981 issue to the March issue of the following year, with Andro Melos as the main character. Considering that UCHIYAMA was not doing comicalizations anymore and that Ritoru kyojin-kun (Little Kyojin-kun) was being serialized in the same magazine at the same time, the editorial team must have been quite persuasive. In any case, UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga shot back to popularity for a second time unexpectedly soon.

And what happens twice happens a third time. The first new TV series in sixteen years after 80 was Ultraman Tiga (1996–1997). As it started airing, UCHIYAMA was asked to lead its comicalization. But this time around, it was not a request for Shogakukan’s magazines but for Uchusen (Space Magazine Uchusen), published by Asahi Sonorama. Uchusen is a seasonal magazine for tokusatsu-fan adults. Of course, this was not to be in a serialized format as in the past but a one-off special only. In an interview with the magazine, UCHIYAMA states, “I don’t think there will be an opportunity for me to draw Ultraman after this.” He no doubt took the job, believing this would truly be the last time. In 1997, UCHIYAMA had become an established creator of seinen magazines, and it was rather difficult to imagine him returning to children’s magazine serializations again. The once-off published in Uchusen, in which Tiga joins hands with the Ultra Brothers to face an unknown, strong enemy, was not an original story typical of UCHIYAMA,15 but an orthodox comicalization reconstructing episode 46 of Tiga, Let’s go to Kamakura! While UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga, as well as many other comicalizations, were revisited quite often in magazines and “mooks” during the 1990s through 2000s, they were mostly treated merely as targets of nostalgia. In terms of the Ultraman series, the Heisei Ultras had their own momentum with more current content, and expanding on the Ultra Brothers—characters from the past—was not mainstream. Yet, after approximately ten years, the winds changed dramatically.

In 2006, Ultraman Mebius was produced to commemorate the Ultraman series’ 40th anniversary. The Heisei Ultraman series following Tiga had woven their own separate storylines and worlds without inheriting any of the former settings,16 but Mebius is set in a world connected to the Showa era Ultraman series, featuring nostalgic themes like the Planet of M-78, the Inter Galactic Defense Force, and the Ultraman Brothers, which had not been revived in a long time. Given this, the opportunity fell to UCHIYAMA, who had always drawn them more captivatingly than anyone else. It started with drawing the illustration novel Za urutoraman mebiusu (The Ultraman Mebius), serialized in the DVD booklet, continued with the comicalization of the movie Ultraman Mebius & Ultra Brothers (2006), which was made public in the summer, and finally did the serialization of Urutoraman mebiusu gaiden cho ginga taisen tatakae! Urutora kyodai (Ultraman Mebius Gaiden: Super Galaxy Wars Fight! Ultra Brothers) (2007–2008). At the same time, the front page of the extra volume Urutoraman mebiusu gaiden cho ginga taisen kyodai yosai o gekiha seyo!! (Ultraman Mebius Gaiden: Super Galaxy Wars Destroy the Giant Fortress!!) (2007), which appeared in the manga magazine CoroCoro Ichiban!, featured the blurb “The Fathers’ Generation Bursts into Tears!? Ultra Brothers Manga.” This Ultraman Mebius Gaiden is a follow-up to the TV series and was published in Shogakukan’s children’s TV magazine Terebikun (Televi-kun) (including its sequel titles) from the June 2007 to April 2010 issues and the reappearance of Melos and the Jackal Army, in particular, was a big hit among longtime fans. Melos also makes a casual appearance in the earlier mentioned The Ultraman Mebius, and it appears that UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga is now considered part of the “official” history of the Ultraman series. This might only seem natural considering the level of its contribution; nevertheless, it is safe to say that this is an unprecedented treatment for a comicalization.

There is also one other title that should not be ignored when considering UCHIYAMA and the Ultraman series: Mega Monster Battle Ultra Galaxy: THE MOVIE, released at the end of 2009. While this is the film version of Ultra Galaxy Mega Monster Battle (2007–2008) and Ultra Galaxy Mega Monster Battle: Never Ending Odyssey (2009–2010), it also served as the debut film of Ultraman Zero, who is still immensely popular today. To briefly introduce the story: The evil Ultraman warrior Ultraman Belial, who was previously locked in the Space Prison by Ultraman King, has returned. Driven by revenge, Belial attacks his homeland and, with his dreadful power, turns the tables on the Ultra Brothers and a line of other experienced heroes. Before long, Belial and his monster army ran rampant, turning the Land of Light to hell. But Ultraman Mebius, who narrowly escapes death, embarks to the far-off universe, planning to make a comeback with the few remaining survivors. Meanwhile, a mysterious Ultra Warrior disguised in a mask and protector called Tector Gear continues his vigorous training under the supervision of Ultraman Leo on the remote Planet K76. Though this is a rather arbitrary overview, I think you can see many similarities with the plot of Sayonara Urutora kyodai (Farewell Ultra Brothers). Several of the staff who worked on the film have mentioned how they were influenced by UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga, and UCHIYAMA himself even makes a cameo appearance.

When I touched on Sayonara Urutora kyodai, I noted that one of the things that make it appealing is the “space-scale” story that departed from the usual pattern of the original Ultraman series, but even preceding this, he wrote several medium-length stories where the Ultra Brothers often had to fight dozens of monsters. These developments were quite difficult to express in films at the time, and they truly made full use of the different mediums of manga. In other words, it opened up other possibilities for the Ultraman series. Now, with former readers having become creators and the development of VFX expanding the limits of visual expression, many works have emerged that look like live-action renditions of UCHIYAMA’s Ultramanga. At present, the Ultraman series continues its traditional storyline setting on Earth, but there are also space opera spinoffs located in the greater galaxy without any people from Earth. Sadly, UCHIYAMA, who laid the foundation for this, passed away in December 2011, but the world of Ultra that he portrayed still continues to grow.

notes