MUKAE Shunsuke

“Otome game” is a video game genre made for women, with features such as the protagonists’ romantic relationships with male characters in the games. Although the genre has a history of almost 30 years, its academic study is still in its infancy. This series will look back at the positioning and the impact of the otome game in the history of video games based on video game works and related materials. In the first installment of the series, we will reflect on the definition of otome games and the process by which their name became widespread, examining the impact brought about by the dissemination of the genre name.

This series examines the place of the genre “otome game” in the history of games and its influence. Although it depends on when we consider as the beginning, the genre is generally said to have started with Angelique (Koei, 1994) (we will discuss it in the next installment). It means the genre has continued for almost 30 years.

However, its academic study is still in its infancy compared to RPGs or bishojo games (date-sim for male players). Engaging in normative discussions at this stage may lead to one-sided criticism with limited perspectives. Therefore, this series aims to describe what otome games are/were, based on the works, related materials, and the voices of the production side and players. Due to space limitations, this cannot be an exhaustive list, but I will give and explain the reasons for selecting each work and the supporting data so that it is clear how the author came to each conclusion. Nevertheless, this article may contain inadequate statements due to a lack of study or may have problems caused by my misunderstandings. I invite readers to make suggestions on those points.

*The names of the developers and publishers mentioned in this series are mostly copied from those printed on their products when they were released or first published, even if the names have changed. If they are still pubslihed today, we use their current names.

Let’s first consider what otome game refers to. Even though there is no clear definition yet, we need to set some conditions to explain it as a coherent whole. As mentioned earlier, research in this field is still in its early stages, and mutual references are weak. KIM (2009), which is relatively widely cited, describes games that are “developed for women, and marketed towards women” as “women’s games.” It also suggests that they often feature the following specifics: “interpersonal (romantic) relationships with the (overwhelmingly male) game characters,” requiring no “quick joystick reflexes or elaborate strategic calculation” and “intimately related to other multimedia products.”1

She cites examples such as Angelique and Harukanaru toki no naka de 3 (Koei, 2004), which Japanese game magazines also introduced as otome games, so it is reasonable to accept her interpretation as the criteria for otome games. However, this would also potentially include BL (boy’s love) games, which focus on romantic relationships between male characters. Therefore, to narrow it down to strictly otome games, we need to add the condition that the protagonist is female.

Platform companies that handle games as part of their business are conscious of this distinction. The platforms for otome games, excluding personal computers and mobile devices, have shifted from PlayStation2 to PSP, PS Vita and Nintendo Switch. PS Store Magazine, the official website of PlayStation Store that covers the first three platforms, describes otome games as “a general term for games where players become female protagonists and fall in love with male characters they pursue.”2 Similarly, the Nintendo Switch otome game feature page on the official Nintendo website describes otome games as “various stories woven by female protagonists within Nintendo Switch. Such dating simulation games for women.”3

Therefore, in this series, otome games are defined as “games developed and marketed for women, featuring female protagonists and romantic elements with male characters,” and system trends and media franchising aspects will be appropriately supplemented as needed.

How do the developers involved think, by the way? Interestingly, it is highly likely the production side might not have first used the term.

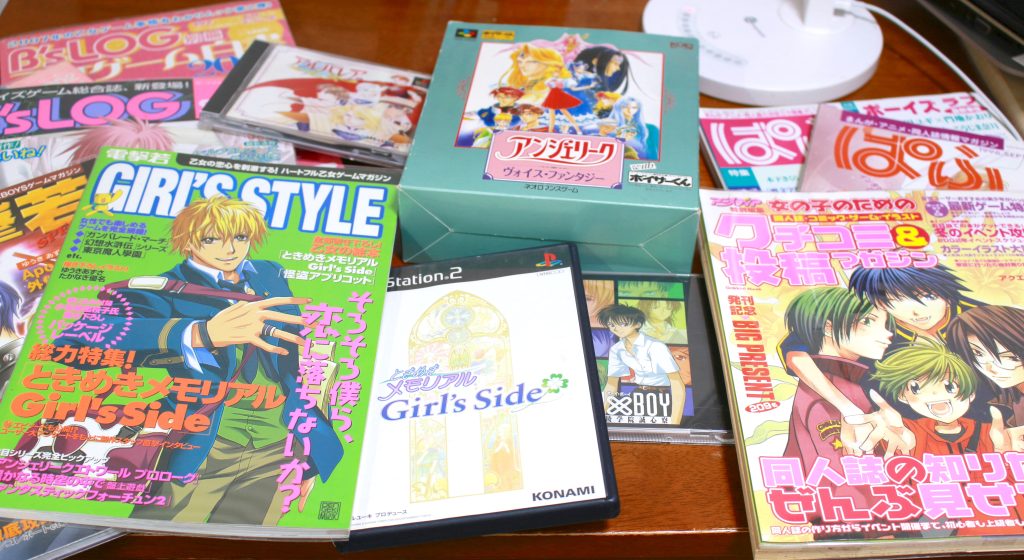

If we limit the information to what we can obtain from the game software itself, including packages and manuals, the first game considered to be an otome game, Angelique, used the term “Neo Romance Game” (throughout its subsequent series). Another early title, Albarea no otome (NEC Home Electronics, 1997), had “otome” in its title, but this was not in the context of defining a genre. Even in the early 2000s, games like Tokimeki Memorial Girl’s Side (Konami, 2002) categorized themselves as “simulation game.” From my research, no games used the term otome game on their package labels up to this point.4

So, when and where did the term originate? It was highly likely that mass media, especially women’s magazines, played a significant role. Although many have ceased publication, (seemingly) the first one specifically targeted towards female gamers was Dengeki waka Special (Media Works, 2001), which later evolved into Dengeki Girl’s Style (now transitioned to an online version, Garusta Online). While the former occasionally referred to readers as otome, it primarily used the term “games for women” rather than otome games. However, in the subsequent issue, Dengeki waka Special GIRL’S STYLE (2002), expressions such as “Stimulating the hearts of otome! A heartfelt otome game magazine” and “The first magazine specializing in otome games” were used, indicating a common understanding of what otome games implied between the publishers and readers. The first issue of B’s-LOG (Enterbrain), launched in April 2002, also featured expressions like “Otome games are much hotter than you think, too!” in its second issue, the 2002 Summer edition.

Before the publication of these specialized magazines, manga and animation magazines aimed at female readers covered such information. For example, the manga information magazine Pafu (ceased publication in 2011) featured several game specials. In its first such special, the September 1996 issue featuring Angelique, the game was categorized as “raising sim.”5 Although the term “female-oriented games” appeared in the July 2001 issue, it was not until the March 2006 issue that the term “otome game” was observed.6

However, among the literature reviewed by the author, the earliest use of this term was indeed found in manga and anime-related magazines. In the first issue of Animedia Special Edition: Magazine for Girls’ Dojinshi, Comics, Games, and Illustrations Reviews & Submissions (Gakken) published in December 2001, the term otome game was observed in the “Girls Game Special Feature” section. Although Animedia or other magazines may have used the term before this, we can trace the origin of the term back to at least this point. I have also checked major game magazines such as Famitsu (KADOKAWA) and platform-specific magazines like SEGA SATURN MAGAZINE (SoftBank), focusing on the release dates of leading titles just in case. But they all used the term “dating simulation.”

Moreover, from the late 1990s, online bulletin board culture began to spread more widely among the public in Japan. On the prominent 2-channel (now 5-channel), a thread titled “Recommended Games for Women” was created as early as July 2000,7 featuring titles like Angelique and Sotsugyo M (Easly Staff, 1998). However, the first thread specifically labelled as an otome game appeared in October 2003,8 indicating a lag in the adoption of the term even in online communities.

Understanding how and when the term otome game became prevalent provides valuable insight into its origins. However, the question remains: why “otome”? While ideally, interviewing the editorial staff of the magazines mentioned above would provide definitive answers, considering possible explanations in advance is worthwhile to facilitate deeper inquiries when the opportunity arises. Here, we can explore this question from two perspectives.

Firstly, there’s the issue of genre classification. We have treated RPGs, bishojo games, BL games, and simulation games in parallel above. However, as I have discussed in my essay about horror games,9 we have better separate them into two categories: gameplay and narrative genre. Following this classification, RPGs and simulations fall under the former, while bishojo and BL games belong to the latter. Otome games also fall under the latter category but have room for diversity in its gameplay genre. Rather than considering date sim or raising sim as overarching terms for these games, it is more apt to adopt a name that encompasses the narrative genre, considering the wide variety of gameplay genres present. For instance, Harukanaru toki no naka de (Koei, 2000) is an RPG and cannot be regarded as the same gameplay genre as Angelique, a raising sim. The disappearance of the term “date sim” from Nintendo’s website may also be influenced by the fact that a diverse range of games, such as visual novels, are being ported and released.

Now it explains why terms like “date sim” or “raising sim” were not adopted as overarching names for these games. Yet, the question remains: why didn’t it become “bishonen” games, the counterpart to bishojo games, or “women’s games”?

It’s likely related to the timing. As previously mentioned, the term otome game began to gain traction around the end of 2001 to 2002. By this time, the term BL had already become established. While the genre itself existed much earlier in novels and manga, at least by 1999, games like St. Valentine Gakuen (DIGITAL MISSION) and BOY×BOY Shiritsu Koryo Gakuin Seishinryo (King Records) were released. In the February 2001 issue, Pafu introduced the latter as a BL adventure game, indicating that genres including “boys” were already present. Introducing a new term like “bishonen games” at this point could have confused players. In this sense, otome remained as a term that didn’t include shojo (girls) or shonen (boys), which were already existing genre names.

On the other hand, the category “women’s game” still exists to some extent. However, since this would also include BL games, it required a new term to emphasize the theme of the genre was heterosexual romance. Finally, the term “otome,” which game magazines used to refer to their readers, remained through the process of elimination. Looking at it this way, the uniqueness of this genre becomes clearer. While terms like bishojo and BL (or GL, girl’s love) games focus on the characters and their relationships, otome games focus on the player.10 This is likely why this term, which readers (players) had implicitly accepted, was pushed as the genre name itself. In magazines like Pafu, Animedia, Dengeki GS, and B’s-LOG, readers could participate through surveys, illustrations, and introductions to dojin works. Beyond just promoting sales of the magazines, engaging readers (players) in such interactions has offered significant benefits for advertisers (developers) wanting to strengthen their connection with customers. We can therefore speculate that they adopted the term otome, with readers’ implicit acceptance, as the genre name for these games.

In conclusion, the diffusion of the term otome game brought benefits not only to the media and production side but also to players. Its widespread adoption helped visualize a broader potential market, leading to increased entry of new developers and shorter production spans (we will discuss it in subsequent parts of this series). For players, the integrated platforms involving numerous developers through features such as advertisements, provision of new release information, and interviews made it easier to find products and related merchandise that matched their preferences. Additionally, players’ voices through posts in such spaces allowed their reactions to be shared with a wide range of stakeholders, potentially leading to overall improvements in the quality of the genre. This feedback mechanism likely served as a fruitful barometer for monitoring market trends, particularly for newer developers.

As KIM mentioned, while this genre tends to favor simple gameplay types (often called “picture-story show”), which may receive negative evaluations in game magazines with predominantly male readership, otome game-focused publications could more effectively extract the points players truly desire. This interaction among developers, media, and players is poised to remain a crucial element supporting this genre, serving as a recurring theme throughout this series.

This installment discussed how the genre name “otome game” spread and its resulting impact. In the next one, we will delve into the pivotal role of Angelique, which essentially determined the direction of this genre, as well as the nascent attempts made before its release and the parallel developments in “women’s games” that occurred around the same time in the States, spanning from the 1980s to the 1990s.

notes

Translation supervision: MUKAE Shunsuke

*URL links were confirmed on May 29, 2023.