IWASHITA Housei

Photo: HATAKENAKA Aya

Manga researcher IWASHITA Housei interviews YAMADA Tomoko of the YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures about the “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” (girls’ manga discussion forum). Following the first part that introduced how MIZUNO Hideko, the founder of the group, established it and discussed the completion of the Shojo manga wo kataru-kai record collection in 2020, the second part will trace the evolution of shojo manga in the 1950s and 1960s, focusing on specific authors and works.

—So far, we discussed the activities leading to the establishment of “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” (hereinafter referred to as Kataru-kai) and the publication of “Shojo manga wo kataru kai kirokushu” (Record collection of shojo manga discussion forum) (hereinafter referred to as the record collection), as well as their impact on manga research. Now, I would like to hear about the trends of shojo manga in the 1950s and 1960s, using materials such as those used in the “Shojo manga wa dokokara kitano? web ten: Genre no seiritsuki ni kansuru shogen yori” (Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition: Testimonies on the establishment period of the genre)(hereinafter referred to as the “Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition”) (https://www.meiji.ac.jp/manga/yonezawa_lib/exh-syoudoko.html) (in Japanese).

YAMADA The materials prepared for this occasion mostly come from the Contemporary Manga Library, so I hope you all come and take a look. The integration of the collections of the Contemporary Manga Library and the YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures (https://www.naiki-collection.jp/) (in Japanese) has made the book search process very convenient.

—I very much enjoyed researching for this interview using the book research.

YAMADA I believe so.

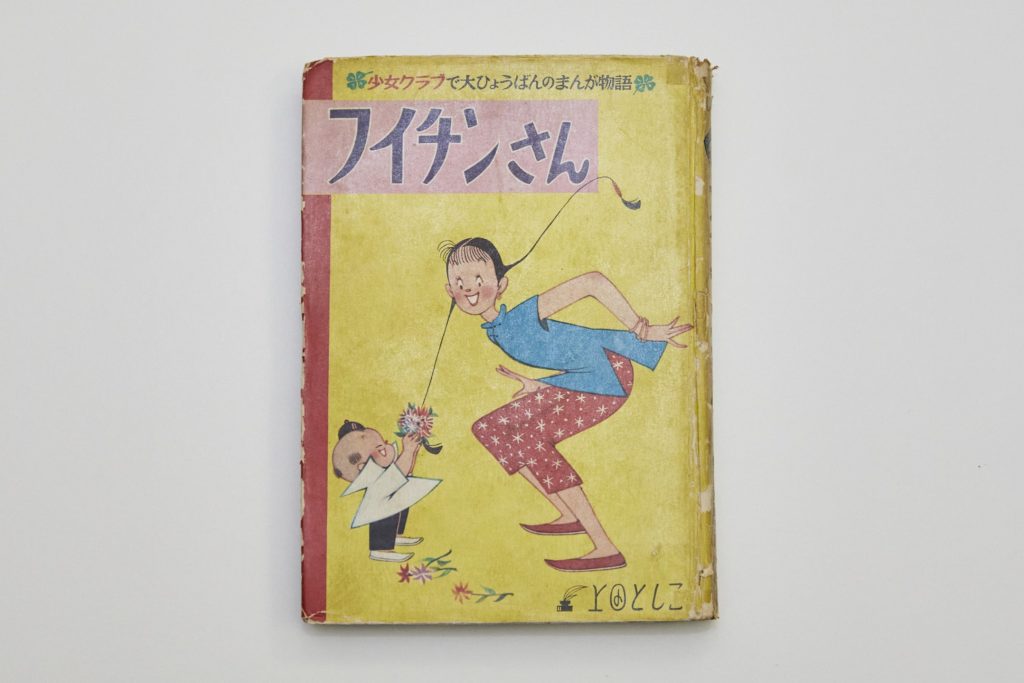

—The 1950s is often said to be a time when there were few female manga artists, and men were drawing shojo manga. However, you often talk about female authors who were active during that era. For example, UEDA Toshiko is indeed one of those authors, having debuted even before the war. How do you position UEDA Toshiko when considering the history of shojo manga?

YAMADA Of course, she is a very important author. Ms. UEDA admired MATSUMOTO Katsudi and decided to become a manga artist. She was one of the few conscious female authors at that time who, with a strong determination to become a manga artist, jumped into the world of manga. It’s also important to note that her main stage of activity was in girls’ magazines. In terms of female authors, there’s also HASEGAWA Machiko, famous for Sazae-san, who has been mentioned by UEDA Toshiko in Kataru-kai. However, Ms. HASEGAWA was a newspaper manga artist, so the context is a bit different in terms of the flow of history.

—HASEGAWA Machiko, of course, has drawn for many girls’ magazines as well, but unlike UEDA Toshiko, she wasn’t primarily focused on girls’ magazines.

YAMADA When considering shojo manga artists, Ms. UEDA stands out as a significant and distinctive figure, akin to a lone star.

—When it comes to Ms. UEDA’s representative work, it’s Fuichin-san (1957–1962), and I really love this piece. The artwork is exceptionally beautiful, to the extent that one might say there’s no other manga like it. In any case, it’s important to emphasize that female authors were already active as early as the 1950s.

YAMADA While it has been commonly believed that male creators dominated the scene in the past, by the late 1950s, female manga artists were already making their mark in girls’ magazines, shining like stars. Examining these magazines reveals just how much they were cherished.

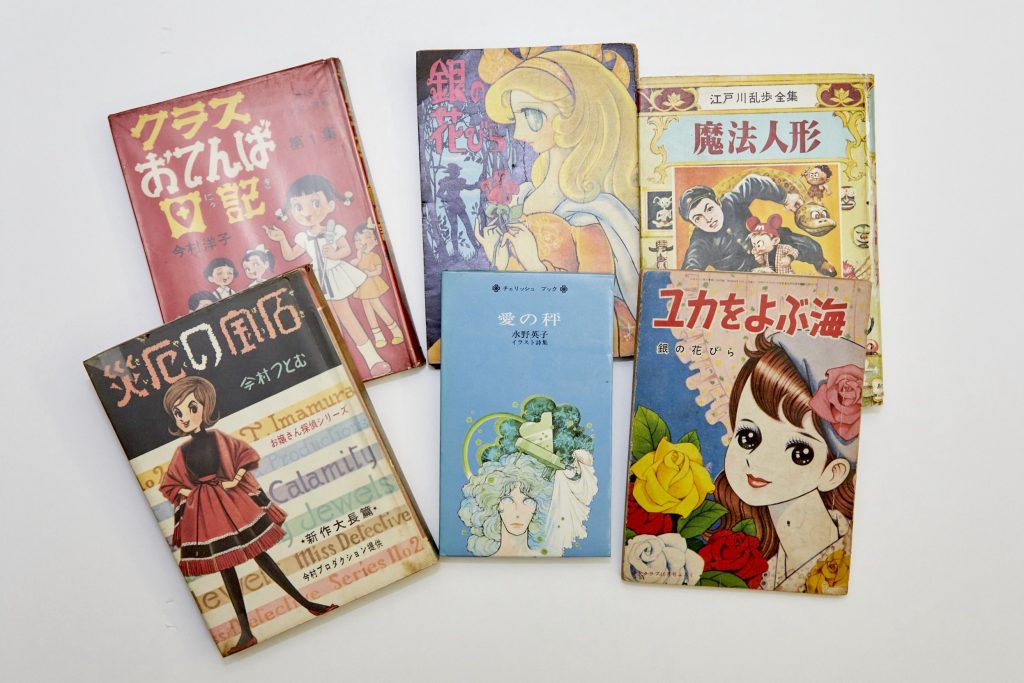

—Someone like MIZUNO Hideko, she was a star creator from the beginning. Drawing illustrations for Shojo Club (Kodansha), she was nurtured carefully, and her first long serialization was Gin no hanabira (original story: MIDORIKAWA Keiko, December 1957 issue to December 1959 issue). Moreover, it appeared on the page immediately following the final chapter of TEZUKA’s Phoenix in the same Shojo Club magazine. Subsequently, as TEZUKA primarily contributed to Nakayoshi (Kodansha) among Kodansha’s girls’ magazines, Ms. MIZUNO firmly established herself as a figure akin to TEZUKA’s successor.

YAMADA Ms. WATANABE and Ms. MAKI, they were both extremely popular for their cute drawings. Seeing such situations, it’s clear that while there were indeed many male authors, it’s a mistake to say there were no female authors. There might have been fewer, but they were highly valued.

—Even if the numbers were small, it seems that the positioning of female authors was quite significant when looking at the pages of the magazines.

YAMADA At that time, magazines had a limited number of manga stories in the first place. Even if we say there were few female authors, it might be like a ratio of 5:4. If there were 10, it could be 6:4, for example. 1

—On the other hand, when reflecting on the work of male authors, including TEZUKA, for example, the period when they were drawing for girls’ magazines is not often considered. Personally, I think this is also a significant issue.

YAMADA Absolutely. I believe female and male authors greatly influenced each other. Imagine there’s a pot with only boys in one scenario, and another pot with both boys and girls—that was girls’ magazines. The mutual influence in that environment might have had an impact on the subsequent development of manga. Because ISHINOMORI Shotaro, CHIBA Tetsuya, and MATSUMOTO Leiji, all of them are excellent at expressing emotions. They’re skilled at drawing cute girls and depicting the dynamics of emotions. Could it be that they learned this from shojo manga? That’s my theory.

—That’s something I also feel. MATSUMOTO Leiji, for example, collaborated with the popular shojo manga artist MAKI Miyako in a husband-wife partnership, influencing each other. I think it’s incredibly important that CHIBA Tetsuya was a popular shojo manga artist. Regarding Mr. CHIBA, HASHIMOTO Osamu even evaluated him as “a complete shojo manga artist,” noting that even when he transitioned to boys’ manga, he hardly changed his style. 2

YAMADA Mr. CHIBA was suggested to try drawing shojo manga because of his rental manga Maho ningyo (Magic doll) (Akashiya Shobo, 1958).

—It’s a detective story based on the works of EDOGAWA Rampo. There’s a scene where the young boy KOBAYASHI cross-dresses, and it’s very charming. Mr. CHIBA’s first hardcover was Fukushu no semushi otoko (revengeful hunchback) (Nisshokan Shoten, 1956), and for a while, he worked on rental manga. Afterward, he started working in girls’ magazines, primarily active in Shojo Club. His first serialization in Shojo Club was Mama no violin (1958–1959), followed by Yuka wo yobu umi (The sea calls Yuka) (1959–1960), which quickly gained popularity.

YAMADA Yuka wo yobu umi is the work where Mr. CHIBA is said to have awakened to shojo manga. It made him realize that just because it’s shojo manga, he doesn’t have to forcibly depict girls as overly “girly”—there’s no need to distinguish them from boys.

—You don’t have to think, “Because it’s a girl, I have to draw her like this,” and you don’t have to draw them as frail. The work became extremely popular when it depicted the protagonist decisively slapping a mean-spirited boy. However, it’s said that Mr. CHIBA also thought, “I don’t need to draw pitiful manga,” but even so, the stories can be pitiful. In Yuka wo yobu umi, for example, just when you think the main character Yuka-chan has finally become happy, her father quietly passes away. Yuka-chan doesn’t notice. The story ends like that. It’s actually quite a pitiful story, but the character doesn’t just get swept away by the environment; she becomes someone who doesn’t just endure but actively faces the situation.

YAMADA Rather than just enduring, she thinks, “Dang it!” If she feels it’s unreasonable, she’ll retort properly. She has a sense of self.

—SATONAKA Machiko often talks about feeling a sense of reality in those protagonist characters and how she always thought of CHIBA Tetsuya as a woman, despite the name implying a man. 3

YAMADA Even after learning that Mr. CHIBA is male, she thought he might be a man with a woman’s heart. That’s how well he captured the hearts of girls. Until I read testimonies from artists like Ms. SATONAKA, I didn’t really feel the popularity among girls. Especially because it’s not overly glamorous. While I knew about the popularity of works like Tomorrow’s Joe in boys’ magazines, I wasn’t aware of his shojo manga works. I realized that CHIBA Tetsuya’s shojo manga was popular when I started looking at rental manga. I noticed there were so many look-alikes of Mr. CHIBA. I realized how popular he was. The art style around the time when MOCHIZUKI Akira made his magazine debut also looked similar. It became clear that everyone thought, “If you can incorporate the feel and style of this person, you can become a successful artist. This is what girls are looking for.”

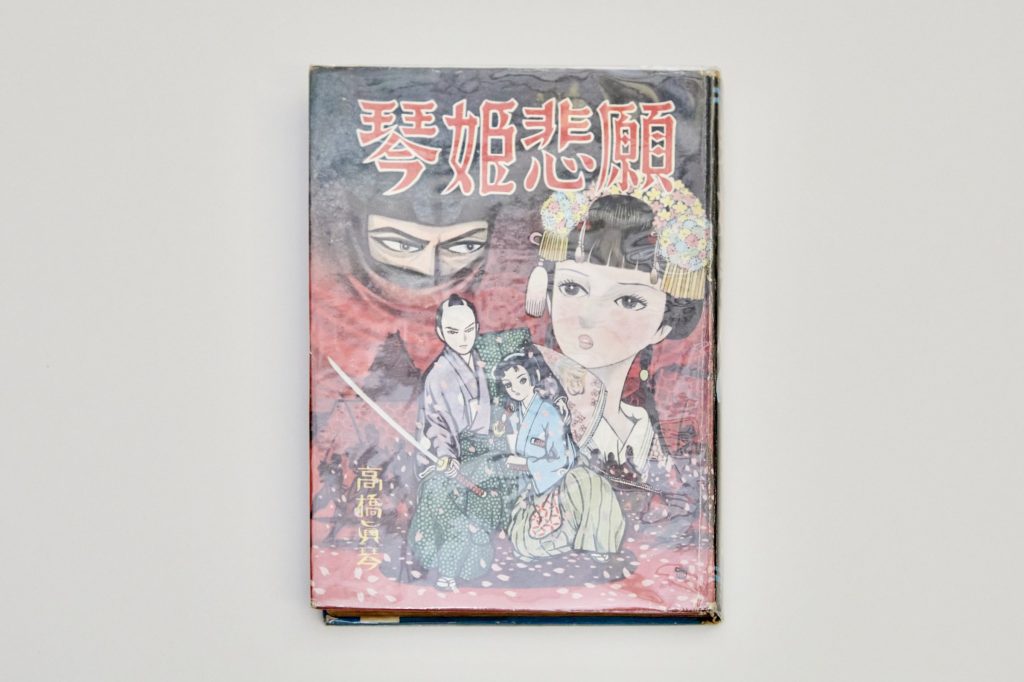

—In that sense, it seems important not only to recognize the existence of female authors but also to highlight the significant influence male authors had on expressions that led to later shojo manga. This applies to TAKAHASHI Macoto as well.

YAMADA In terms of expression, I think they mutually influenced each other, regardless of gender. When reading the records of Kataru-kai, it seems that established manga artists were not consciously aware of Mr. TAKAHASHI. While there might be a root in TAKAHASHI Macoto’s work, they probably incorporated what they found beautiful, expressing themselves like playing jazz, and through that, they collectively developed what everyone would consider as the so-called “shojo manga-like” expression.

—There might be a sense that TAKAHASHI Macoto’s work is not consciously seen as “manga.” Since the 1960s, he has mostly been seen as an illustrator.

YAMADA Even back then, manga artists saw him as “A creator of illustrated stories and illustrations,” while illustrators saw him as “A manga artist.” He himself has mentioned that. As for him, he didn’t consider himself purely a manga artist or an illustrator; he was thinking of creating something new.

—It was novel for artwork in this style to be treated as “manga.” Until then, a style of art was one of the criteria used to distinguish between manga and illustrated stories, and that boundary was broken. Up to a certain period, if it was artwork in such a lyrical style, it would be called an illustrated story. However, from around the late 1950s, even this style started to be referred to as “manga.” I think he might be one of the individuals who pushed forward this shift.

YAMADA Yes, I believe so. All manga artists’ art style become like Mr. TAKAHASHI’s. FUJIMOTO Yukari has also analyzed this, but when you look at shojo manga from that time, all works are truly becoming “TAKAHASHI Macoto.”

—There are people who look surprisingly similar. With tremendous influence, TAKAHASHI Macoto has continued to draw cute girls primarily in this style.

YAMADA He wanted to draw cute girls. Initially, it was akahon. In Akai kutsu (Enomoto Horeikan, around 1953), he even drew the cover himself.

—In rental manga, the cover is not drawn by the manga artists themselves, but in Mr. TAKAHASHI’s case, he often drew the covers himself. He had already established his art style by that time.

YAMADA However, in the beginning, the cover art and the interior art were different. The interior had what we would now call “manga” art for that time.

—As time passed, the distinction gradually disappeared, and even the kind of illustrations drawn on the covers began to be accepted as “manga.” This shift occurred around the late 1950s, perhaps in 1956 or 1957.

YAMADA By the time of his magazine debut, it had already become like that.

—TAKAHASHI Macoto had a considerable influence on the expression known as “style drawing.” FUJIMOTO Yukari positions the presentation of the superposition of panels (full-length portraits that fill the entire page) in Norowareta Coppelia (Cursed Coppelia) (Shojo, December 1957 issue, Kobunsha) as the precursor to this trend. 4 The origin of style drawing and the stars in the eyes is often a subject of debate.

YAMADA Regarding the stars in the eyes, Ms. MIZUNO discussed it in Kataru-kai. I also wrote about it in the text for the “Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition.” The stars drawn by Ms. MIZUNO are at the center of the pupils, but Mr. TAKAHASHI’s eye stars are not in the middle; they are located around the iris. It seems to be the highlight star that appears when taking a photograph. Even though we call them both “eye stars,” there is a difference.

—In Kataru-kai, there’s quite an extensive discussion about rental manga’s shojo manga.

YAMADA For instance, MURE Akiko says she has focused solely on tankobon (a book published in a single volume), which in this context refers to tankobon of rental manga.

—Even so, she has drawn a considerable number of works, including shorter pieces, in magazines.

YAMADA Well, moreover, she made her debut drawing under the name MIYAZAKI Akiko in a newspaper. Learning various things through her participation in Kataru-kai, I was truly astonished at the immense volume she created. As I mentioned in the explanation of the “Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition,” Tsuyu no ashita ni (1959) was published as the first book in the Himawari Book series by Wakagi Shobo. Choosing her as the first author for the inaugural volume indicates that she was already the go-to author for shojo manga at that time. After that, she drew a large number of new works of tankobon that were about 200 pages for Wakagi, but she mentioned that the original artwork no longer exists.

—At that time, it was often the case that the original artwork didn’t survive, especially in the context of tankobon for rental manga; they weren’t usually returned to the artist.

YAMADA Not returning them was the norm.

—Publishers essentially purchased them.

YAMADA Yes, that’s correct. Changing the subject, on the record collection’s cover and the flyer for the “Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition,” the authors are arranged in order of their debut.

—As for the debut, there’s a question of which work to consider as the debut.

YAMADA Indeed, the debut the authors have in mind and the actual debut year can sometimes differ.

—Sometimes, it’s really unclear whether a certain book was actually published.

YAMADA That’s true for Ms. WATANABE. In the case of Ms. UEDA, she herself doesn’t consider her prewar works as her debut. She says she doesn’t count those as her debut, but we count them here.

—I wonder where exactly the debut starts for IMAMURA Yoko. In reality, even though Ms. IMAMURA is the one drawing, her father, IMAMURA Tsutomu, is sometimes credited under the name.

YAMADA Ojosan tantei (Miss Detective) series was IMAMURA Yoko’s breakthrough, in my opinion. In this series, it wasn’t just IMAMURA Tsutomu alone; both names were used. The father drew women in a way that wasn’t quite right, so she taught him, “This is cooler,” and then he said, “Well then, you draw it.” The title font is clearly different from IMAMURA Tsutomu’s. The title, Miss Detective, also gives off a distinctly Yoko vibe.

—Ms. IMAMURA portrayed relationships with boys in the Kurasu otenba nikki (Class’ tomboy diary) series in Shojo (1957–1958). In that regard, she is indeed a very significant author.

YAMADA Without losing to the boys.

—Kurasu otenba nikki developed further, becoming one of her representative works, the Chako-chan no nikki (Chako-chan’s diary) series (1959–1970). In Chako-chan, there’s an episode where she rates the boys in her class.

YAMADA She’s quite a harsh girl, isn’t she? (laughs)

—Like, “Nagashima-kun gets 100 points! “(laughs). It portrays girls who have an interest in normally cool boys. In shojo manga, from the 1950s to the 1960s, how to depict romance was a highly significant theme. During that time, it wasn’t something you could openly portray.

YAMADA Ms. IMAMURA mentioned in Kataru-kai that when she drew a scene where the protagonist intentionally drops a handkerchief for a boy to pick up to catch his attention, she received a letter saying, “Are you a pervert?” She thought that if she drew it again, they would tell her it’s not allowed. However, the editor-in-chief of Shojo at that time was KUROSAKI Isamu, who later launched Josei Jishin (Kobunsha) and Bisho (Shogakukan) and was referred to as the “god of women’s magazines.” He conveyed something along the lines of “It has to be done that way.”

—That’s a famous episode, indeed. Kurasu otenba nikki was a project where letters from readers were turned into manga, and during that time, they also adapted sad stories and experiences sent in by readers into manga or stories. This is also a tradition in girls’ magazines.

YAMADA It sold incredibly well. Kurasu otenba nikki was published as tankobon by a rental manga publisher Kinransha. After a while, it was drawn by a different author, not IMAMURA Yoko, and more than 20 volumes were published.

—As a pioneer in romance in shojo manga, MIZUNO Hideko is also highly significant. In Shojo Club, after the serialization of Gin no hanabira, she actively depicted romance in Hoshi no tategoto (1960–1962). It was quite challenging for the works of that period. In Gin no hanabira, the focus was on the relationship between an elder brother and his younger sister.

YAMADA Hoshi no tategoto is clearly a romantic story.

—The depiction of male characters is also ambitious. They have a good physique with a solid chest, exuding a masculine charm.

YAMADA They are attractive. Slender and handsome.

—Drawing such a male image and presenting it as a romantic interest is indeed pioneering.

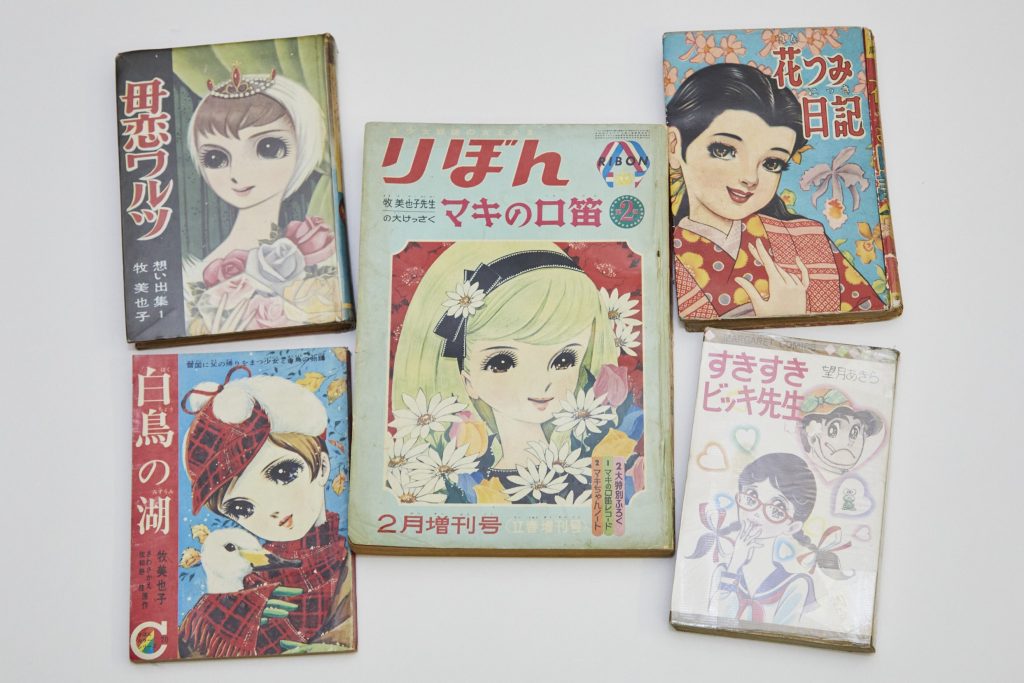

YAMADA Absolutely. What younger manga artists say about Ms. MIZUNO is the grand scale of her works. At that time, in shojo manga with many familiar themes, she delivered dynamic content that made you forget about poverty, and everyone loved that. The drapes of the dresses were stylish. On the other hand, someone like Ms. MAKI would draw stories about everyday life, but the art is just cute.

—Ms. MAKI’s artwork, when seen in the magazine pages of that time, makes you think, “Here it comes.” This is bound to be very popular. Overwhelmingly cute.

YAMADA The setting is mostly in Japan, but there’s a dignified aspect of looking up a bit, which is charming…

—The clothes the characters wear are also glamorous, and the houses they appear in are splendid buildings.

YAMADA Because they’re Japanese girls, their eyes are a bit reserved. Somewhat small. At that time, there were girls who were greatly influenced by manga and took up ballet, and that influence came from Ms. MAKI. Around this time, Ms. MAKI’s husband, MATSUMOTO Leiji, was drawing mainly shojo manga under the name “MATSUMOTO Akira,” and they even collaborated. Before his break through around the 1970s with Otoko Oidon, I think Ms. MAKI might have been more popular than her husband.

—That’s how overwhelming the popularity was at that time.

YAMADA Because she drew for various magazines. She drew girls whom everyone admired and aspired to be like: pure but with a clear ideal, a strong feeling hidden inside. In the advertisement for the new release of “Kisekae ningyo Licca-chan” (Dress-up doll Licca-chan) in the October 1967 issue of Ribon (Shueisha), Ms. MAKI’s name appears as the supervisor. At that time, Ms. MAKI’s artworks were featured on the package, box, and the front of the Licca-chan house.

—Indeed, the girls drawn by Ms. MAKI embodied the aspirations of the girls of that time. Not only were the artworks cute, but the fashion was also popular. In the serialized Maki no kuchibue (1960–1963) in Ribon, there was a project called “Maki-chan Style,” where the clothes worn by the main character were presented as gifts to readers in almost every issue.

YAMADA Ms. MAKI, after this, transitioned to manga for adult women and continued to draw many works there, but not many people are aware of it. People haven’t fully grasped the greatness of Ms. MAKI.

—She’s also a pioneer in ladies’ comics. Another example of a manga artist who worked in both shojo manga in the 1950s and 1960s and later in adult women’s manga is WATANABE Masako. Ms. WATANABE was also a popular storyteller from the early days. She played a crucial role in the development of romantic depictions in shojo manga.

YAMADA Yes, she portrayed romantic relationships involving slightly older and more mature characters, like the mothers of the main characters.

—The main characters are very young children, yet the stories revolve around the romance and marriage of older sisters or parents. She depicts very mature relationships. For example, in Hadashi no Princess (1966), the love story between the father, who is the Grand Duke of a small country, and a Japanese woman becomes the central theme.

YAMADA It’s wonderful, especially the female characters. Ms. WATANABE often sets her stories in foreign countries, featuring characters with fair blonde hair, gorgeous dresses, creating a world that makes you want to live in that house. She skillfully weaves in tales where scary things happen within that enchanting setting.

—One of her representative works, Glass no shiro (1969–1970), is indeed such a story. On the other hand, she is also adept at depicting a realistic, everyday world. In terms of artistic style, during a session in Kataru-kai, composer and author on shojo manga, AOSHIMA Hiroshi pointed out that one characteristic feature is the absence of a line under the nose in the depiction of profiles.

YAMADA While Ms. WATANABE said, “I thought I was drawing it,” when she looked at it, it turned out she indeed wasn’t drawing it. She’s a fantastic artist. Regarding her expression style, Ms. WATANABE didn’t draw the “stars in the eyes,” but she mentioned that she made a unique effort in the lines of the iris, which she had thought about and worked on.

—Even if she didn’t draw “stars,” it’s clear that the expression of eyes is crucial in shojo manga. Despite not having many direct stylistic similarities with others, Ms. WATANABE had a considerable influence on later artists. HAGIO Moto, for example, mentioned that when she was struggling, she would reread WATANABE Masako’s manga. 5

YAMADA Ms. HAGIO mentioned that Ms. WATANABE had excellent paneling, and if she ever felt lost with panel layouts, she would read Ms. WATANABE’s manga. The storytelling is clear and skillful.

According to what UEDA Toshiko has said, when these three artists—Ms. WATANABE, Ms. MIZUNO, and Ms. MAKI—appeared, she felt like she might be done. These three artists had momentum, excellence in quality and quantity, and were considered representative figures of what shojo manga should be like

—The records of Kataru-kai and the “Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition” are expected to become crucial resources when discussing shojo manga from the 1950s and 1960s in the future. However, on the other hand, since the participating artists and editors are limited, there are aspects that haven’t been discussed, and facets that aren’t visible from this perspective. What do you think are the things that should be talked about in the future, and what aspects should be explored further?

YAMADA In terms of important artists for shojo manga during this period, there has been quite a bit of discussion about TEZUKA Osamu and ISHINOMORI Shotaro by the participating manga artists, but I believe other artists like UMEZU Kazuo and YOKOYAMA Mitsuteru are also important. HOSOKAWA Chieko of Oke no monsho (Emblem of the Royal Family) (1976 onwards) also debuted in the monthly magazine era.

—In the aspect of not having discussed UMEZU Kazuo, amidst the various trends in shojo manga, while Ms. WATANABE is considered an authority in this genre within Kataru-kai, there is a need to delve further into the lineage of “scary manga.” For instance, regarding vampire-themed works, there is a book titled Shojo manga wa kyuketsuki de dekiteiru: Koten Vampire comic guide (Shojo manga is made of Vampires: Classical Vampire comic guide) (Hojosha, 2018) by NAKANO Jun and OI Natsuyo from the private library “Shojo manga kan.”

YAMADA If Kataru-kai had continued, I believe such discussions would have taken place. In the first and second forums, there was a realization that not many participants knew much about rental manga or akahon. For the third and fourth forums, manga artists who drew rental manga and representatives from publishing houses were invited. If the forum had continued, we might have reached discussions about genres. But in that sense, it might be good to think that we are still in the middle. Everyone continues to explore. There are still many enjoyable things left.

—After reading the record collection, it’s important not to conclude with just “I see.” We need to think about the continuation properly.

YAMADA If there were more people interested in shojo manga from this period. It might not be appropriate to make a direct comparison, but if there had been a gathering of prominent individuals discussing boys’ manga from the 1950s and 1960s, I feel there would have been a surge of excitement, and numerous books might have been published.

—I hope that more people with an interest in shojo manga from this period will emerge. In that sense, we welcome opinions like “That story is missing” or “This story is missing” after reading the record collection.

YAMADA If you feel that way, please do investigate! I’d appreciate it. I’ve also been involved in various activities, such as organizing exhibitions on supernatural manga (like the “YONEZAWA Yoshihiro’s postwar supernatural manga history exhibition—Genealogy of supernatural and horror manga 1948–1990” held at Meiji University YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures in 2018), I’m doing things, fragmented here and there.

—In terms of the history of shojo manga, you held an exhibition featuring SUZUKI Mitsuaki, who made significant contributions to nurturing the next generation through “Betsu ma manga school” (Bessatsu Margaret manga school). (“Betsuma manga school no seiritsu to SUZUKI Mitsuaki exhibition” [The establishment of the Betsuma manga school and SUZUKI Mitsuaki exhibition] at Meiji University YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, 2014).

YAMADA SUZUKI Mitsuaki was active in the 1950s, but his health deteriorated, leading to his retirement within a decade. However, afterward, he played a role in mentoring the next generation and contributed to the development of many well-known female manga artists. His name is mentioned in the footnotes during Kataru-kai.

—Even today, shojo manga magazines feature something akin to manga workshops, and the approach to nurturing newcomers is different from that of boys’ magazines. There are various aspects that Kataru-kai hasn’t covered, and you have been addressing them in various ways.

YAMADA It would be great if, in that way, fragmented efforts could be connected, and like a puzzle, the necessary pieces could be neatly filled in.

—In terms of the history of shojo manga, it’s necessary to delve into the prewar era, and surprisingly, the period after the contents compiled by YONEZAWA in Sengo shojo manga shi (A history of postwar shojo manga) (Shinpyosha, 1980) lacks a well-organized summary. That might be the most neglected aspect. While the records of Kataru-kai have significantly filled in the gaps for the 1950s and 1960s, when it comes to the 1980s, 1990s, and subsequently the 21st century, there seems to be a situation where there’s no reliable map. Regarding shojo manga in the 1990s to the 2000s, there are studies on magazines like Ribon and Ciao (Shogakukan), conducted by researchers such as SUGIMOTO Shogo, but there is still a lot that is not understood and not compiled.

YAMADA To put it broadly, as we move into the 1980s, there is the world of ladies’ comics, and in the 1990s, Boys’ Love (BL) became prominent. Furthermore, from ladies’ comics, Teen’s Love (TL) emerged, delving a bit deeper into the sexuality of the younger generation. While there has been considerable discussion about these genres, especially BL, research or in-depth exploration into mainstream shojo manga is relatively scarce.

—In recent years, there may be occasions to discuss under the umbrella term “women’s manga,” where both the reader base and topics covered have expanded. However, when it comes to the heart of it—or rather, what might now be considered a side stream—“ordinary shojo manga” from the same era is not well understood.

YAMADA No, even for adult-oriented “women’s manga,” we might question how well they are understood. While it’s possible to connect bestsellers like constellations, it’s challenging.

—Thinking along those lines, there’s still so much that hasn’t been discussed about “today’s shojo manga.” Collecting the words of the authors is, of course, necessary, and there’s plenty to consider.

YAMADA I’m not an expert in women’s history. I’m just someone knowledgeable about shojo manga. I think there are many aspects of shojo manga history or women’s history that haven’t been thoroughly explored. Additionally, not only shojo manga but manga itself is often skimmed through, considered something not worth preserving. Even from the perspective of the history of technology and printing, manga uses many technigues to keep costs low, and sometimes these aren’t recorded. I recently heard that if you provide the data of a tankobon manga published in Japan to overseas publishers, they can’t reproduce it due to various local rules. I realized there’s history here that needs to be picked up. The world of manga requires a lot of work to reclaim its history the more you delve into it.

—While the Kataru-kai record collection has been compiled, the task of reclaiming the history of shojo manga is something that will continue to unfold from now on. It would be great if you could write a book on the history of shojo manga (laughs).

YAMADA It would be tough to do it alone, so it would be nice if you, IWASHITA, could assist in compiling it together (laughs).

notes

YAMADA Tomoko

Manga researcher. Born in 1967 in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. Engaged in activities such as manga-related exhibitions, interviews, and writing. Notable works include editorial cooperation on Gendai Manga Hakubutsukan (Contemporary manga museum) 1945–2005 (Shogakukan, 2006), overall supervision for Ballet Manga—Leap above the beauty— (Kyoto International Manga Museum, 2013), writing for What Is Shōjo Manga (Girls’ Manga)? (British Museum “The Citi exhibition Manga” exhibition catalog, Thames & Hudson, 2019), and writing for “MIZUNO Hideko—Shojo manga no rekishi wo torimodosu tame no kagi” (The key to recovering the history of girls’ manga) in Sotokushu MIZUNO Hideko Jisaku wo kataru (Special Feature: MIZUNO Hideko talks about her own works) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2022), among others. From 2005 to 2010, she worked as a temporary staff member at the Kawasaki City Museum specializing in manga. Since 2009, she has been the exhibition staff at Meiji University’s YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, currently serving as a special staff member. From 2022, a member of the selection committee for the Arts Encouragement Prize.

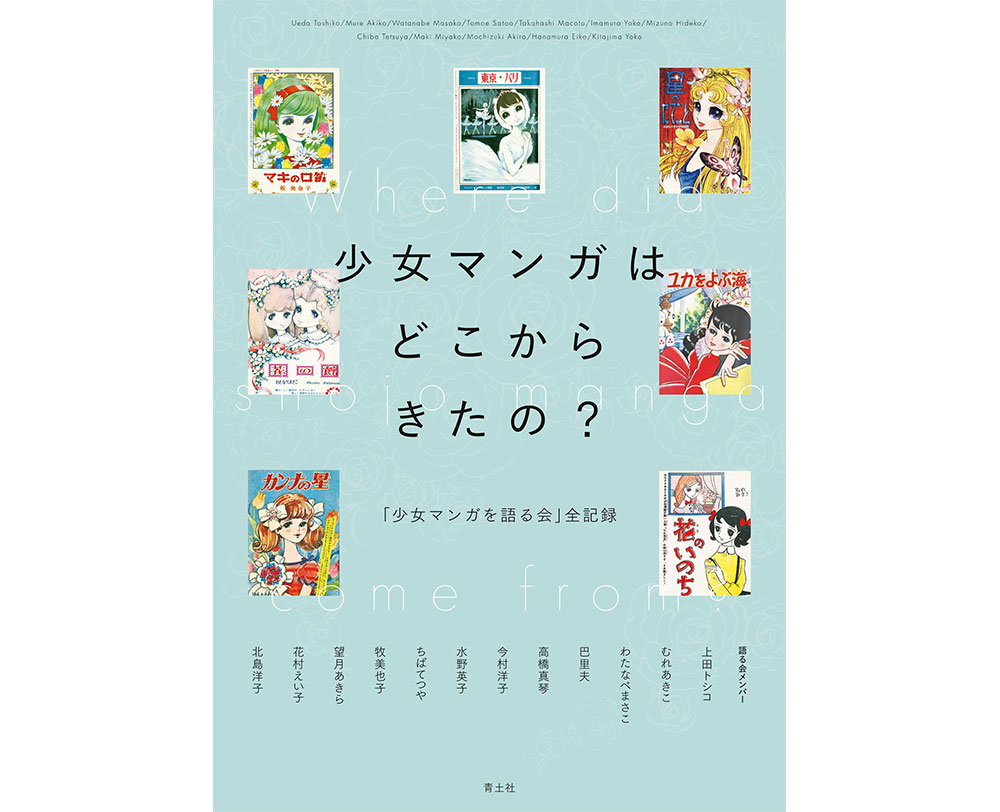

Shojo manga wa dokokara kitano? “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” zen kiroku (Where did shojo manga come from? The complete records of shojo manga discussion forum)

Authors: UEDA Toshiko, MURE Akiko, WATANABE Masako, TOMOE Satoo, TAKAHASHI Makoto, IMAMURA Yoko, MIZUNO Hideko, CHIBA Tetsuya, MAKI Miyako, MOCHIZUKI Akira, HANAMURA Eiko, KITAJIMA Yoko

Editors: YAMADA Tomoko, MASUDA Nozomi, KONISHI Yuri, SODA Yon

Price: 2,860 yen (including tax)

Published on May 31, 2023

Published by Seidosha

http://www.seidosha.co.jp/book/index.php?id=3806 (in Japanese)

Japan Society for Studies in Cartoons and Comics The 22nd Convention

Dates: July 1 (Sat.), July 2 (Sun.), 2023

Venue: Sagami Women’s University, Online sessions are available.

On July 2, a symposium titled “Saikento—shojo manga shi” (Reconsidering the history of shojo manga) is scheduled to be held. Representative manga artists from “before” and “after” the late 1960s and those actively involved in reprints and editing will be invited to discuss the significance of reweaving the history of “shojo manga.”

https://www.jsscc.net/convention/22

(in Japanese)

*Interview date: December 16, 2022

*URL links were confirmed on June 16, 2023