IWASHITA Housei

Photo: HATAKENAKA Aya

“Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” (girls’ manga discussion forum), initiated by manga artist MIZUNO Hideko, took place from 1999 to 2000. The 1970s is known as the era when revolutionary changes occurred in shojo manga marked by the creation of enduring masterpieces. Manga researcher IWASHITA Housei conducted an interview with YAMADA Tomoko from the YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, who participated in the discussion forum and contributed to the creation of the record collection. This article provides an overview of the discussion forum and explores the transition of shojo manga in the 1950s and 1960s.

—Today, I would like you to talk about “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” (hereinafter referred to as Kataru-kai). It was a discussion forum initiated by manga artist MIZUNO Hideko, with the participation of various manga artists and editors. The forum took place four times from 1999 to 2000. I understand that the “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai kirokushu” (Record collection of shojo manga discussion forum) (hereinafter referred to as the record collection) compiling these discussions was released in 2020.

YAMADA Yes, that’s correct. The final document was from the year 2000, and the record collection was published the year before last.

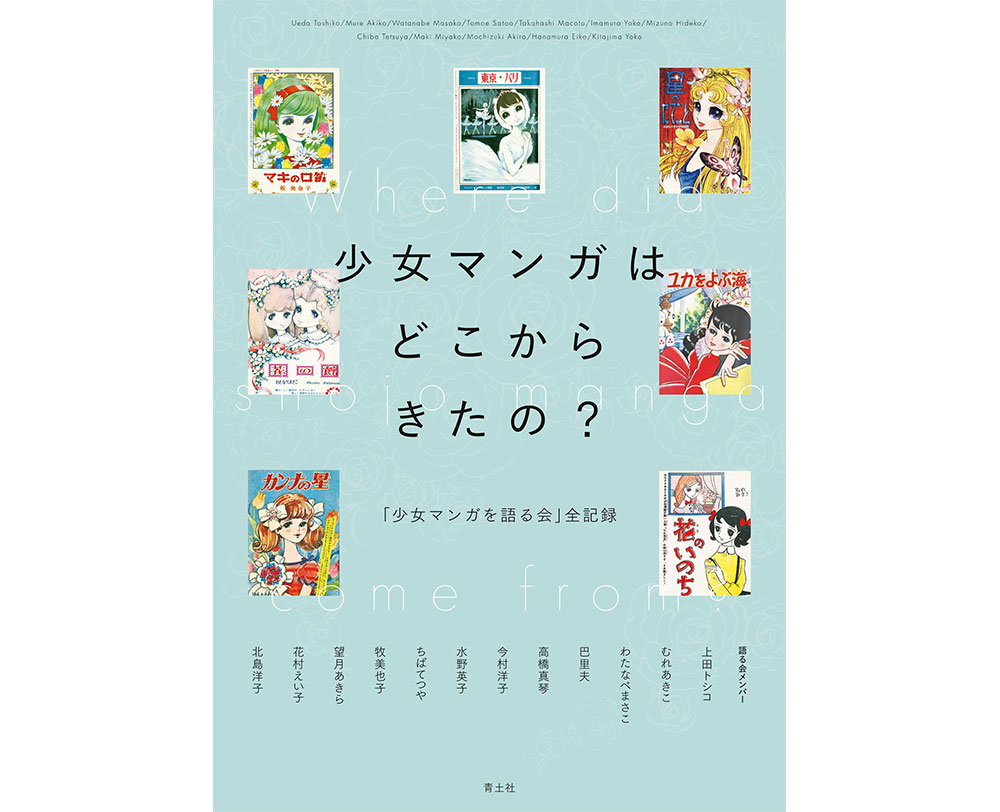

—It indeed took over 20 years until the record collection was released. I’ve learned about Kataru-kai on various occasions in the past and even cooperated to some extent with the research program. At the time of the publication of the record collection in 2020, it served as a report on the results of the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research. Now, I congratulate you on the publication by Seidosha titled Shojo manga wa dokokara kitano? “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” zen kiroku (Where did shojo manga come from? The complete records of shojo manga discussion forum).

YAMADA Thank you so much.

—This Kataru-kai and its record collection are both significant in many respects, but I’m particularly interested in hearing about Kataru-kai as a pivotal “starting point” for various things. The term “starting point” specifically refers to one aspect: it served as a starting point for the subsequent activities of the participating manga artists. Reflecting on their own work after participating in Kataru-kai prompted some to compile autobiographies, speak again about their own creations, and even led to reevaluation and republication of their works, all sparked by the connections made during Kataru-kai. This has contributed to the reevaluation of shojo manga from the 1950s and 1960s, a period that had not received much attention before. In other words, Kataru-kai is not only a starting point for manga studies but also a starting point for the reexamination of the history of shojo manga in the field of manga studies, particularly shojo manga studies. Another significant aspect is that your cooperation in Kataru-kai appears to have been a substantial catalyst and starting point for your subsequent work. I would like to inquire further about Kataru-kai as such a “starting point.”

Firstly, as mentioned in the articles contributed to this record collection, 1 I would like to hear about the background of how Kataru-kai was established and how you became involved. It seems that one catalyst was MIZUNO Hideko attending “Shojo manga no sekai ten” (the world of shojo manga exhibition) held at the Kawasaki City Museum in 1998. Could you share more about that?

YAMADA I had the opportunity to meet Ms. MIZUNO once before, but it was during Kataru-kai that we had a chance to sit down together and have a leisurely conversation for the first time. The first time we met was at the Shojo Club alumni gathering (January 28, 1998) of manga artists and editors who were involved in the magazine titled Shojo Club (Kodansha).

—An interview with Ms. MIZUNO about this event is also featured in the August 1998 issue of COMIC BOX (Fusion Product), which had a special feature on shojo manga in the 20th century. In this issue, your commercial magazine debut critique, titled “Manga yogo ‘24-nen gumi’ wa dare wo sasu noka?” (Who does the term ‘Year 24 Group’ refer to?) is also included. 2

YAMADA It has been discussed during Kataru-kai, but ISHINOMORI Shotaro passed away on the day of the event. I was also present at the event and had the opportunity to meet Ms. MIZUNO. However, we didn’t engage in extensive conversations during that meeting.

—You first met her at the Shojo Club alumni gathering, and later, she visited “Shojo manga no sekai ten”.

YAMADA During that time, as I was preparing for “Shojo manga no sekai ten” and writing “Manga yogo 24-nen gumi wa dare wo sasu noka?” I began to realize the importance of researching works from before the 1970s. It was around this period that Ms. MIZUNO came, expressing her interest in recording the history of shojo manga from before the 1970s, citing the lack of existing records. She said, “I want to document the history of shojo manga, as there is no record. Would you be willing to help?” Given that it aligned with my own awareness of the issue, I took on the role of the questioner and, along with my manga research colleagues, including HOSOGAYA Atsushi, who was then the curator of the manga department at the Kawasaki City Museum, and my colleague, or rather, senior researcher AKITA Takahiro, provided various forms of assistance. That marked the beginning. What I did was limited to that, as at the time, Ms. MIZUNO intended to compile the records herself. However, actualizing this proved to be challenging, and gradually, I took on tasks such as finding a publisher, summarizing transcripts, specifying annotations, and conducting additional research.

—In terms of your interest in the period before the 1970s, “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga ten” (exhibition of shojo manga as seen in published materials) held concurrently with “Shojo manga no sekai ten” in 1998 might have been another catalyst.

YAMADA “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga ten” was the first exhibition I supervised and curated. The content of this exhibition was later taken to the Angoulême International Comics Festival in France (as part of the “Shojo manga eno sasoi ten” [invitation to shojo manga exhibition] within the Japan feature of the 28th festival held in 2001). The exhibition “shojo manga no sekai ten” was brought in by a planning company. While it was probably one of the first excellent exhibitions of shojo manga in public institutions in Japan, considering it was primarily focused on Shueisha-affiliated publishers (Shueisha and Hakusensha), I thought it might be too limited to represent the world of shojo manga on its own. So, I expressed a desire to create an exhibition in the adjacent gallery that would explore a broader range of shojo manga using materials only, and that was made possible.

—The phrase “seen in published materials” suggests that original artworks were not used due to such circumstances. The content follows the history from the Meiji and Taisho eras, focusing on girls’ magazines, and it also introduces akahon manga.

YAMADA The akahon collection was housed in Kawasaki. Regarding girls’ magazines, for those we didn’t have in our collection, we borrowed the inaugural issue of what is considered the first girls’ magazine, Shojo Kai (girls’ world) (Kinkodo, 1902), from the Yayoi Museum, and we also borrowed valuable materials from the International Institute for Children’s Literature, Osaka back when it was still located in Senri Chuo. While this exhibition covered shojo manga from prewar times to the present, I felt that there was still a long way to go in terms of introducing shojo manga from before the 1970s. By the way, I believe this exhibition was probably the first to introduce the comic market in a public facility. While comic market participants might be perceived as predominantly male, I used materials to convey that, in reality, there were more female participants.

—That is also mentioned in “Manga ni wa nandaka mienai kaikyu ga aru mitai” (There seems to be some invisible class in manga) in Soshi (October 2004, Soshisha).

YAMADA It seems that Ms. MIZUNO visited me after seeing both the exhibition “Shojo manga no sekai ten” and the adjacent “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga ten” exhibition. In the “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga ten” exhibition, we introduced Ms. MIZUNO’s work Yellow Ribbon and U.MIA (a collaborative pen name with MIZUNO Hideko, ISHINOMORI Shotaro and AKATSUKA Fujio) at the Shojo Club section. However, in the exhibition “Shojo manga no sekai ten,” no manga artists from before the 1970s were featured. Perhaps Ms. MIZUNO sensed something from that.

—At that time, there seemed to be areas where shojo manga from before the 1970s, especially from the 1950s and 1960s, wasn’t quite in focus. Perhaps this is still the case today.

YAMADA Nowadays, various shojo manga, including works by Ms. MIZUNO, are available in electronic books. However, back then, there was a sense of urgency that if things continued as they were, we might truly lose the ability to read them.

—Especially for the manga artists who were active in the 1960s or earlier, it wasn’t an era where serialized works were compiled into single volume books (tankobon).

YAMADA There was no trend of publishing tankobon for shojo manga before 1967. When I was a young child, manga was widely looked down upon in society, and shojo manga was even more lightly regarded. Therefore, there was a sense of crisis that if things continued as they were, the history of shojo manga wouldn’t be carried on. This feeling persisted even in 1998. While now there’s an unbelievable world where you can read a lot through e-books, just having them available may not be appreciated unless someone is already a fan of older works.

—It’s not something one can reach without having an active interest.

YAMADA Even for those who want to cultivate an active interest, shojo manga is still perceived as something “with sparkly eyes and old-fashioned,” and only teasing is applied to shojo manga from all generations.

—Yes, that’s true. The phrase “big eyes” is still used. They are indeed large, but I want to ask what’s wrong with that.

YAMADA They are large, but there’s significance to that. The other day, when I spoke as a guest lecturer at a university and showed old shojo manga, a student remarked, “Old manga, they all have big eyes and look similar, but manga today is different for each artist.” I explained that even though the eyes are big, there are differences when you look at each one individually, varying from artist to artist. When I told the students that when I mentioned this to the manga artists of that time, they said, “In our time, there was a variety.” The response was like, “Oh, really?” People tend to focus on the noticeable and teasable aspects without looking at each work individually, leading to the conclusion that there was a time like that. The preconception that “shojo manga is something like that” hinders one from properly examining its content. People get misled by the discourse that there was nothing great in shojo manga before the 1970s and that amazing things happened in the 1970s, bringing forth many wonderful works.

—It’s like the historical view of the 1970s or the Year 24 Group perspective. Such views still persist.

YAMADA Maybe not even a historical perspective. I used to work at a manga specialty bookstore, and when I talked about shojo manga to my younger colleague, even when looking at HAGIO Moto, she said, “I like YOSHIDA Akimi, not these sparkling eyelashes.” It’s like a label for shojo manga is moving around in various places. Amidst that, shojo manga from before the 1970s is getting buried. Even though you often say that TEZUKA Osamu is the origin of shojo manga, it’s pointed out that only Princess Knight is mentioned.

—For TEZUKA, only Princess Knight is recognized and directly connected to the 1970s, with everything else slipping through. I think there might still be such aspects today, but it was even more pronounced back then. Collecting statements from manga artists of the 1950s and 1960s at Kataru-kai was important in the sense that it questioned the situation.

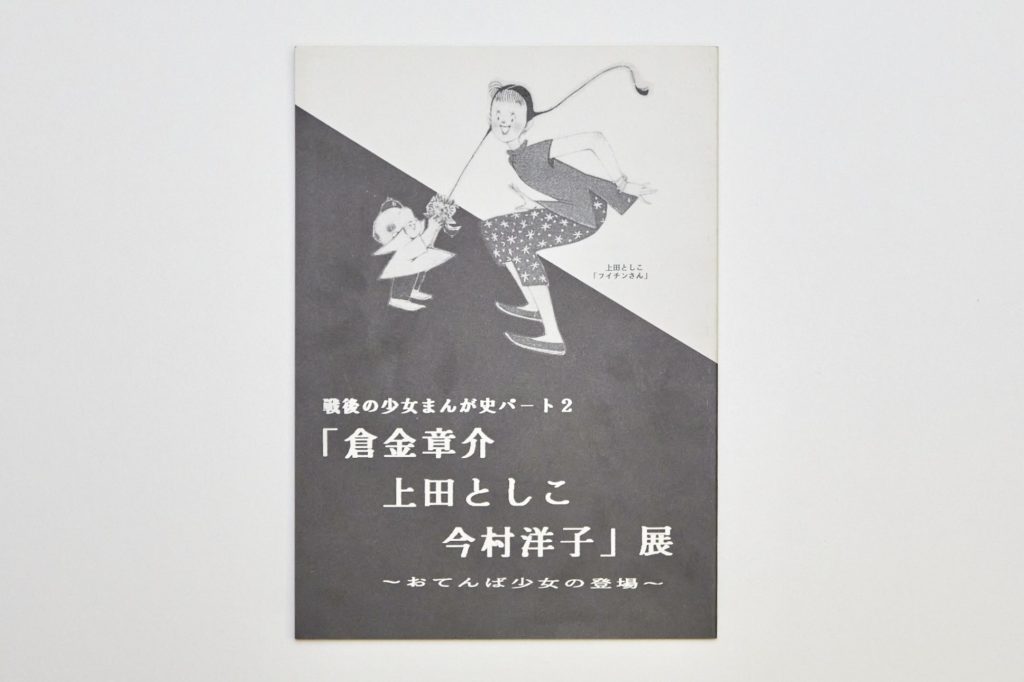

YAMADA I have no idea if it was thanks to Kataru-kai, but someone from the Yayoi Museum participated as an audience in the third Kataru-kai forum, and afterward, the Yayoi Museum hosted exhibitions titled “MAKI Miyako, MIZUNO Hideko, WATANABE Masako Exhibition” (October to December 2000) and “KURAKANE Shosuke, UEDA Toshiko, IMAMURA Yoko Exhibition” (July to September 2001). Except for Mr. KURAKANE, all the manga artists participated in Kataru-kai. HANAMURA Eiko and Ms. WATANABE also published autobiographies by themselves. I think the influence of Kataru-kai can also be seen in the fact that CHIBA Tetsuya started talking about shojo manga properly in a book where he discusses himself.

—In 2008, Ms. WATANABE published Manga to ikite (Living with manga) (Futabasha), and Ms. HANAMURA published Watashi, Mangaka ni nacchatta!? Mangaka HANAMURA Eiko no gagyo 50-nen (I became a manga artist!? Manga artist HANAMURA Eiko’s 50 years in the field) (Magazine House) in 2009. Mr. CHIBA also talked quite a bit about his work in girls’ magazines in CHIBA Tetsuya ga kataru “CHIBA Tetsuya” (CHIBA Tetsuya talks about “CHIBA Tetsuya”) (Shueisha, 2014). There were various unseen influences.

YAMADA I’m glad if that’s the case.

—On the other hand, Ms. MIZUNO originally had the awareness to leave records of her generation, took the initiative as the organizer of Kataru-kai, and has been actively speaking since then. She even collaborated with MARUYAMA Akira, the then editor of Shojo Club, and supervised Tokiwaso Power! (Shodensha, 2010), a collection of shojo manga works by manga artists gathered at the Tokiwaso apartment building.

YAMADA Regarding that book, she specifically asked me if it was okay to use the title “Shojo Manga Power! —Tsuyoku, Yasashiku, Utsukushiku (strongly, tenderly, beautifully) —” for the exhibition held at the Kawasaki City Museum in 2008. She liked the exhibition title. It was originally coined by Dr. TOKU Masami of California State University.

—In confirming the long journey leading to the publication of the record collection, I also reviewed my past emails. The first exchange I had with you regarding Kataru-kai was around the summer of 2011. At that time, you came to the International Institute for Children’s Literature, Osaka for research, and we met along with the staff from Tosho no Ie.

YAMADA I remember I stayed for about 1 to 2 weeks during that time.

—I also visited the International Institute for Children’s Literature, Osaka and contributed to the research. I remember that, at that time, the text-smoothing process was already quite advanced. I read something quite close to its current state up to the second installment. However, it took about another 10 years from that point to compile it into a record collection.

YAMADA As for Ms. MIZUNO’s initial vision, she wanted to publish a book like Bessatsu Taiyo Kodomo no Showa shi: shojo manga no sekai I・II (Special Issue of Taiyo History of Children’s Showa: World of shojo manga I・II) (Heibonsha, 1991), a book with plenty of beautiful and glamorous illustrations. However, this book, supervised by YONEZAWA Yoshihiro, was preceded by Shinpyosha’s Sengo shojo manga shi (Postwar shojo manga history) (1980) and had a strong aspect of a pictorial record. Due to that, I thought that it might be easier to resolve copyright issues by first publishing a text-rich publication with ample citations for illustrations, and then later releasing a picture-heavy magazine-like book. However, even if we wanted to add annotations, it was not easy to research everything alone. The major development came when shojo manga researcher MASUDA Nozomi obtained the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research. The theme was to compile testimonies of shojo manga artists from the era when monthly magazines were thriving. I think Ms. MASUDA had various plans, but I proposed, “If that’s the theme, there are actually records that haven’t been compiled for a long time…” From that point onwards, with Ms. MASUDA’s involvement, we were able to ask for cooperation for investigations and writings by offering some remuneration. This involved soliciting assistance from collector and researcher SODA Yon who generously contributed to the part of rental books; Tosho no Ie, which operates a shojo manga website and has edited many books; HIDAKA Toshiyasu, an excellent shojo manga researcher who is now an associate professor at Kumamoto University; and AOU Kozue, a writer and editor.

—With the impressive cooperation of such distinguished individuals, the richness of the annotations is truly remarkable. It’s quite moving.

YAMADA I wanted to make the content understandable even for young readers, so I ended up adding annotations to everything that seemed unclear. That’s how it turned out.

—If you want to know about publishing companies related to rental books, reading this record collection feels like the most straightforward approach. There are so many annotations that could be useful as guides for future reference. In that sense, the accumulation of manga research over the past 20 years, particularly the focused study of shojo manga magazines, has come to fruition. If it had come out earlier, it might not have reached this level of density.

YAMADA I also carefully reviewed the statements of manga artists. Even though the episodes themselves were accurate, there were often discrepancies in the timeline of events—sad or happy incidents within the manga artist’s life. They might overlap with memories from their representative works.

—Everyone has long careers, and since they’ve been drawing manga diligently every day, their memories can get mixed up.

YAMADA Manga artists’ job isn’t really about talking, so that’s fine as it is. There probably weren’t many opportunities to be asked about or talk about this period. However, by piecing together various people’s stories and conducting research, you start to understand what their experiences were during this time, extremely regrettable events happened around this period, and they were happy during this time. The real truth starts to become visible. We reflected what we learned in this way because it made the record collection stronger as a material. Of course, before the publication, we had the content confirmed by the manga artists and their families.

—I believe that such an attitude is deeply connected to your stance as a researcher.

YAMADA In the first place, many of my original writings were such that the annotations were more useful than the main text, and that might be evident here (laughs).

—That’s the important point (laughs). From the time when Kataru-kai was taking place, you expressed concerns in PUTAO Summer 2000 issue (Hakusensha) with “Watashi ga manga kenkyusha wo nanoru wake” (Why I call myself a “manga researcher”) and in Comic Fan Issue 12 (Zassosha, 2001) with “Manga kenkyu ni tsuite kini naru koto” (Things I’m concerned about regarding manga research). In those articles, you pointed out the fear that, in traditional manga criticism and research, references to materials and literature were not explicitly stated, and the discussions built up over time were not being acknowledged.

YAMADA At that time, I thought that everyone who was called “otaku” should just say they were “manga researchers.” Even now, although I am a staff member of the YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, I am not a teacher. I don’t have a researcher number, so I am like a stray researcher or a freelance researcher. Regarding Kataru-kai, until it took the form of a book, I, as a stray researcher, was in charge, and after it became a book, I, as a library staff member who can create exhibitions, took over and created the exhibition.

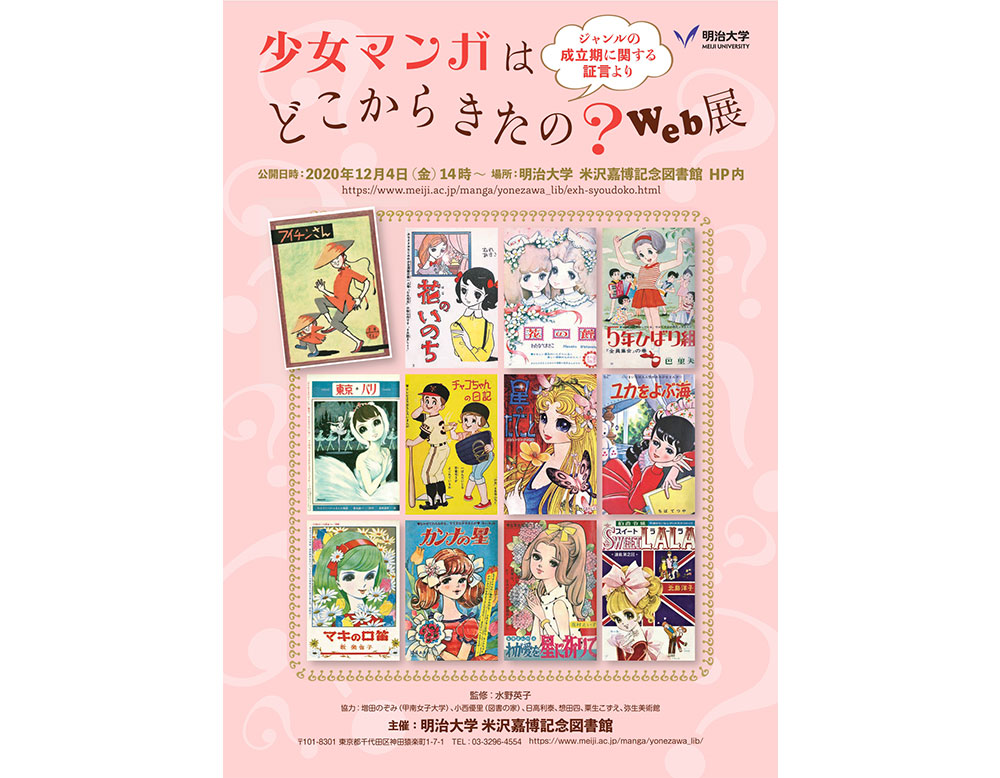

—That’s the currently ongoing “Shojo manga wa dokokara kitano? web ten: Genre no seiritsuki ni kansuru shogen yori” (Where did shojo manga come from? web exhibition: Testimonies on the establishment period of the genre) (https://www.meiji.ac.jp/manga/yonezawa_lib/exh-syoudoko.html) (in Japanese). The exhibition title became the title used when the record collection was commercially published.

YAMADA In this case, it’s because Ms. MIZUNO had always wanted it as the title of the book. When it comes to an exhibition, there’s also curation, which is another form of editing. We were going to create an exhibition to fit into the display space of the facility, but suddenly, due to the impact of the new coronavirus, we couldn’t go to borrow the original drawings. As a result, the staff at the library suggested presenting it on the web, and with incredible speed, we requested the manga artists, and it took its current form. We were able to overcome this with the support of the library staff, the generosity of the manga artists and everyone involved, and my long experience in this industry.

—You refer to yourself as a “stray researcher,” but considering that the Japan Society for Studies in Cartoons and Comics was established in 2001, around the time of Kataru-kai in 2000, it could be said that most of those engaged in manga studies were “stray researchers” who simply loved manga. As a connecting space for such researchers, “Manga shi kenkyu kai” (Society for studies of manga history) was already active around this time, generating various achievements in manga studies and criticism during the 2000s, and you were also involved in it.

YAMADA The name “Manga shi kenkyu kai” is also listed as a cooperator for the exhibition “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga.” It was only during this exhibition that we actively presented ourselves as an organization and engaged in specific activities outside of our regular meetings.

—In the dialogue between you and Mr. MIYAMOTO 3 on the theme of Manga shi kenkyu kai, you mentioned that at the time, research in the non-academic sphere was more advanced, and there was a conscious effort to bridge the gap between such grassroots accumulation and academia.

YAMADA Bridging the gap between grassroots efforts and academia is still crucial today. I hope that young people in organizations like the Japan Society for Studies in Cartoons and Comics will continue to inherit and uphold this. If we don’t value those who are working at the grassroots level, I believe that research may not thrive or could eventually fade away.

—That awareness is greatly reflected in this record collection. The members contributing to annotations include individuals conducting research in non-academic settings as well as researchers affiliated with academic institutions, creating a mix of both.

YAMADA Yes, that’s right. It naturally became that way when people who were willing to contribute gathered and joined in.

—While research in the academic domain is progressing, and I believe its results are undoubtedly contributing here, I also feel the importance of continuous, barrier-free exchange between academia and grassroots. SODA Yon made significant contributions.

YAMADA I’m really grateful.

—In the aspect of combining the strengths of grassroots research and academia, it feels like the entirety of manga studies leading up to this point is consolidated here. It’s very significant that this has turned into a book, being read, and spreading in various forms. Speaking of those involved in grassroots efforts, Tosho no Ie has become indispensable to shojo manga research. 4

YAMADA I met with Tosho no Ie before Kataru-kai, and they have been supporting my desire to publish this record collection from the beginning. The first encounter was when KISHIDA Shino, a member of Tosho no Ie, and her friend came to the exhibition “Shojo manga no sekai ten,” which we’ve been discussing earlier. At that time, Ms. KISHIDA was passionately talking about wanting to do a “Ballet Exhibition.” I handed her a simple list of ballet manga that I had written on loose-leaf paper at that time.

—That eventually led to “Ballet Manga—Leap above the beauty—” (Kyoto International Manga Museum, 2013).

YAMADA In hindsight, yes. At that time, even though I expressed the desire to do a ballet manga exhibition, it never materialized, so I waited for the opportunity. Later on, KURAMOCHI Kayoko, a curator at the Kyoto International Manga Museum, appeared and said she wanted to do a ballet exhibition. She asked if I would be the overall supervisor. Having KURAMOCHI as the missing piece was crucial. So, Tosho no Ie also joined us to work together. We had a training camp for it.

—We had a training camp (laughs). I also had the opportunity to participate.

YAMADA Our connection started through the meetings at the exhibitions “Shojo manga no sekai ten” and “Shuppan shiryo ni miru shojo manga ten” in 1998, and through reflections on “Manga yogo 24-nen gumi wa dare wo sasu noka?” Tosho no Ie originally started as a research group for a website that delved into shojo manga centered around the works of HAGIO Moto. The name “Tosho no Ie” is also taken from Ms. HAGIO’s manga (“Tosho no Ie” is the name of an archive facility appearing in Marginal). So, we had talked about wanting to work together on Ms. HAGIO’s pieces someday. That eventually led to the commentary on Ms. HAGIO’s work in KAWADE Yume mook HAGIO Moto Shojo manga kai no idai naru haha (the great mother of the shojo manga world) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2010).

—Starting with those experiences, Tosho no Ie’s impressive activities began. They started handling entire features, such as in Sotokushu MIHARA Jun Shojo manga kai no hamidashikko (Special Feature: MIHARA Jun The outsider in the shojo manga world) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2015). Now, when it comes to feature books related to shojo manga, it’s synonymous with Tosho no Ie. I’ve also always been grateful to Tosho no Ie, and in Sotokushu MIZUNO Hideko Jisaku wo kataru (Special Feature: MIZUNO Hideko talks about her own works) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2022), I wrote a commentary (“Naze MIZUNO Hideko wa ‘onna TEZUKA’ to yobareta no ka? Gin no hanabira hiraku made—MIZUNO Hideko to Shojo Club [Why was MIZUNO Hideko called ‘female TEZUKA’? Until the silver petals bloom—MIZUNO Hideko and Shojo Club]).

YAMADA That special book on Ms. MIZUNO is fantastic. It really goes all out (laughs). There seems to be a mutual contribution between the work on the Kataru-kai record collection and Tosho no Ie’s involvement in books such as Sotokushu WATANABE Masako 90 sai, ima nao ai wo egaku (Special Feature: WATANABE Masako, age 90 – Never stop drawing “Love”) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2018) and Kawaii! Shojo manga fashion book Showa shojo ni mode wo oshieta 4 nin no sakka (Kawaii! Shojo manga fashion book, four authors who taught fashion to Showa girls) (Rittor Sha, 2020). HIDAKA Toshiyasu is also involved in Ms. WATANABE’s book. The research done there is reflected here, making it even more comprehensive.

notes

YAMADA Tomoko

Manga researcher. Born in 1967 in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. Engaged in activities such as manga-related exhibitions, interviews, and writing. Notable works include editorial cooperation on Gendai Manga Hakubutsukan (Contemporary manga museum) 1945–2005 (Shogakukan, 2006), overall supervision for Ballet Manga—Leap above the beauty— (Kyoto International Manga Museum, 2013), writing for What Is Shōjo Manga (Girls’ Manga)? (British Museum “The Citi exhibition Manga” exhibition catalog, Thames & Hudson, 2019), and writing for “MIZUNO Hideko—Shojo manga no rekishi wo torimodosu tame no kagi” (The key to recovering the history of girls’ manga) in Sotokushu MIZUNO Hideko Jisaku wo kataru (Special Feature: MIZUNO Hideko talks about her own works) (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2022), among others. From 2005 to 2010, she worked as a temporary staff member at the Kawasaki City Museum specializing in manga. Since 2009, she has been the exhibition staff at Meiji University’s YONEZAWA Yoshihiro Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures, currently serving as a special staff member. From 2022, a member of the selection committee for the Arts Encouragement Prize.

Shojo manga wa dokokara kitano? “Shojo manga wo kataru-kai” zen kiroku (Where did shojo manga come from? The complete records of shojo manga discussion forum)

Authors: UEDA Toshiko, MURE Akiko, WATANABE Masako, TOMOE Satoo, TAKAHASHI Makoto, IMAMURA Yoko, MIZUNO Hideko, CHIBA Tetsuya, MAKI Miyako, MOCHIZUKI Akira, HANAMURA Eiko, KITAJIMA Yoko

Editors: YAMADA Tomoko, MASUDA Nozomi, KONISHI Yuri, SODA Yon

Price: 2,860 yen (including tax)

Published on May 31, 2023

Published by Seidosha

http://www.seidosha.co.jp/book/index.php?id=3806 (in Japanese)

Japan Society for Studies in Cartoons and Comics The 22nd Convention

Dates: July 1 (Sat.), July 2 (Sun.), 2023

Venue: Sagami Women’s University, Online sessions are available.

On July 2, a symposium titled “Saikento—shojo manga shi” (Reconsidering the history of shojo manga) is scheduled to be held. Representative manga artists from “before” and “after” the late 1960s and those actively involved in reprints and editing will be invited to discuss the significance of reweaving the history of “shojo manga.”

https://www.jsscc.net/convention/22

(in Japanese)

*Interview date: December 16, 2022

*URL links were confirmed on June 16, 2023