SAKAMOTO Nodoka

Interviewer: TAKAHASHI Hiroyuki

MANABE Daito, a creator, and ISHIBASHI Motoi, an engineer, both members of Rhizomatiks, have garnered awards in the Art and Entertainment divisions of the Japan Media Arts Festival. What did the Japan Media Arts Festival mean to them? We present a re-edited interview with the two from the book Japan Media Arts Festival 1997–2022: 25 Years of Progress (CG-ARTS, 2023), a collection of records of the festival held 25 times.

—The two of you began receiving awards at the 11th Japan Media Arts Festival in 2007; however, even before that, did you attend to see the festival?

MANABE From the early years, I used to go and see it fairly often.

ISHIBASHI I remember going to see the festival too. At the time, I was still a student in the Department of Systems and Control Engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, so I think it must have been in the early years. At around the same time, I attended a performance of MPI X IPM (Music Plays Images X Images Play Music) (1997), a work created in a collaboration between IWAI Toshio and SAKAMOTO Ryuichi, in Ebisu, and that was when I first learned about the field of media art. At the time, Mr. IWAI was doing a residency 1 at the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS), so I decided to go to IAMAS instead of going to graduate school.

—Rhizomatiks was founded as a company in 2006, and I understand that Mr. ISHIBASHI officially joined the company a little later. When did you two first meet?

ISHIBASHI It was in 2004, when Daito, a graduate of IAMAS, took over as a lecturer at Tokyo University of the Arts, where I had been serving. Since our enrollment periods at IAMAS didn’t overlap, we had not met until then.

—I would like to trace the activities of the two of you at the Japan Media Arts Festival, while following the technological trends in the world. First, the iPhone was released in the United States in 2007. Your work SONIC Floor, which was created in the same year, won a Jury Selection award in the Art Division of the 11th Japan Media Arts Festival. Was this the first time that a work you jointly created has been featured at the Japan Media Arts Festival?

MANABE Before that, there was a work titled path installative concert that won an award, and my name was credited. However, the collaboration with Mr. ISHIBASHI in this work is the first time.

—In the same year, in addition to this work, you also produced the dance performance work TRUE 2 and collaborated with Apichatpong Weerasethakul on his video installation work Unknown Forces. This period seems to be the beginning of your collaboration. In TRUE, you created a very technical and elaborate stage set, and it seems to me that this project led to your later evolution toward stage direction.

MANABE Yes, that’s right. However, in terms of stage production, I had been working in that area for some time, and it was around this time that Mr. ISHIBASHI and several others joined me. As for our collaboration, 2004 was the start. In the early days, we created interactive installations for entrances to commercial facilities and events.

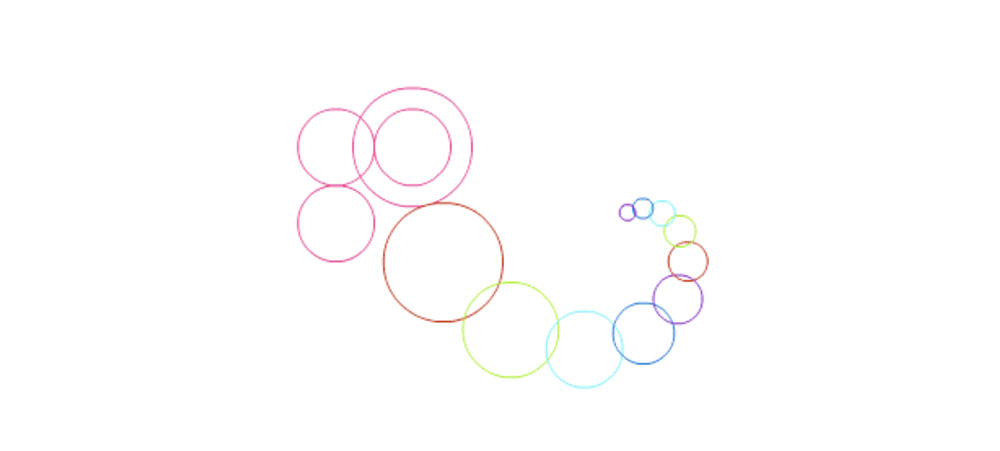

—Next, at the 13th festival in 2009, another of your work Pa++ern was awarded as a Jury Selection in the Art Division.

MANABE Pa++ern turned out to be a unique and interesting work. The project involved hacking an industrial sewing machine to create embroidered T-shirts using patterns generated from Twitter posts. Twitter started in 2006 and API 3 became available gradually, and then in the advertising world, so-called participatory projects utilizing SNS began to be announced from around 2008 and became popular.

—What roles do each of you play in this work?

MANABE There was a culture of hackers who deliberately created a programming language that was even more difficult to read by making the terms look like emoticons. I was into it at the time, and I was in charge of designing and implementing the language. I was also very particular about the appearance of the language itself.

For example,

!!<^o^>!!o(?v?i),,

*?^(<i)….!<<<+(v),(>^>^)^^<^ (>)…+(v), >> +(^),< vvv+ >>vv>+(^), >>+>> <+(v), (>^),(v<)..v+vi(>>v???),.. (<<?),,!!!!+(<<v??*),,

It looks like these.

ISHIBASHI The Twitter posts were converted into patterns in Daito’s difficult language, and I was in charge of converting them into sewing machine data. Industrial sewing machines are programmed using ternary numbers, a remnant of the old punch card system, but the information was extremely closed to the extent that it could not be picked up at all… However, by chance I happened to find a page that explained the data structure. We also created a website where people could check the generated patterns and proceed with the purchase of T-shirts. Actually, the site was created by the Rhizomatiks web team with the help of an external, highly skilled Flash 4 coder.

MANABE Although only my name is listed as a representative, the Way Sensing GO + by 4nchor5 La6 (Anchors Lab), a hackerspace that Mr. ISHIBASHI and I founded in 2008, and my personal project Face visualizer, instrument, and copy also received a Jury Selection that year. With the rise of trends like DIY and hacking, hackerspaces were also experiencing a bit of a boom worldwide. The Way Sensing GO + was the result of a workshop where the participants hacked toys and musical instruments to create chain reactions. It was a time when we were also having fun with that kind of thing.

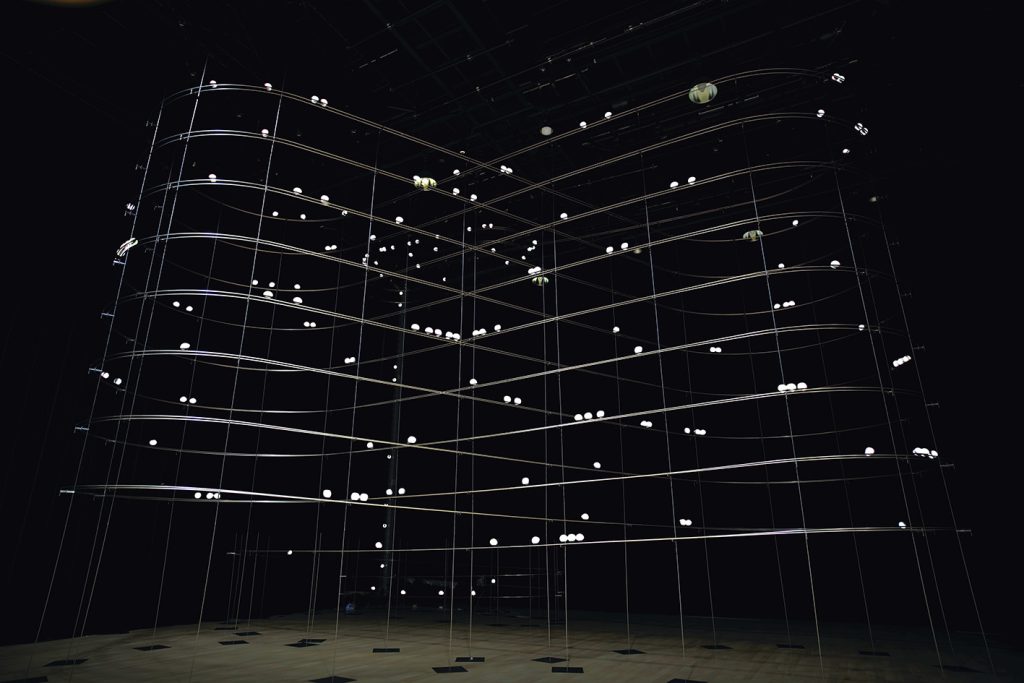

—At the 15th Japan Media Arts Festival in 2011, you received the Excellence Award in the Art Division for particles. That was a fairly large-scale work, and it must have been difficult to display it at the award-winning exhibition.

ISHIBASHI Yes, it was. For the exhibition at the National Art Center, Tokyo, we adjusted the height of the rails to suit the venue. I think the good thing about this kind of work is that it can be customized according to the exhibition space. This work won awards at both the Japan Media Arts Festival and Ars Electronica, so we had ample opportunities to exhibit it afterwards, including overseas. Apart from in connection with this work, we were also invited to participate in regional and overseas exhibitions at the Japan Media Arts Festival.

—In the following year of 2012, at the 16th Japan Media Arts Festival, you finally won the Grand Prize in the Entertainment Division for your Perfume “Global Site Project.” Then you went on to win the same award again at the 17th Festival in 2013 for the sound installation Sound of Honda/Ayrton Senna 1989. Around the same time, you also began collaborating with Perfume and MIKIKO, and your work began to receive greater public recognition and gain momentum. Could you please share with us any anecdotes concerning these works? For example, the Perfume “Global Site Project” included the distribution of motion capture data, didn’t it?

MANABE Shortly before that, in 2008, Radiohead made a splash by releasing the 3D 5 data and processing source code used in the music video for their song House of Cards so that it could be used for derivative works. It was during this time, when the trend towards open-sourcing of data used in artworks and music videos was emerging, that we were approached about a new promotional project for Perfume. At the time, Nico Nico Douga (now Niconico) and other companies already had a culture of derivative creation, with 3DCG characters dancing using motion data that imitated Perfume’s choreography. This was the first Perfume-related project that I had planned and realized on my own, so I was very attached to it. Sound of Honda/Ayrton Senna 1989 was in a rough state of completion, and I was asked if there was anything more I could do. At that stage, there was only the sound element, so I proposed a plan to visualize the driving path by installing LEDs around the circuit, and once this plan was approved, I was put directly in charge of its implementation.

ISHIBASHI I wasn’t on site at the time, but a bulk order of LEDs I had placed through a Chinese mail order site was stopped by customs just before the setup. Daito contacted me to ask if I had any backup plan, and I remember replying, “There is no way we can prepare 1,000 units that quickly.” (laughs)

MANABE I can say this now, but in the end, the large number of LEDs we had purchased did not arrive, so we went to Sound House’s warehouse in Narita the day before the setup, bought as many as we could, and drove directly to the Suzuka Circuit (in Mie Prefecture). The work was difficult because of the sheer amount of material, but due to the high rental cost of the venue, we had to work efficiently within a very limited time, so we performed a thorough simulation of the wiring and installation. In addition, for example, cables can become expensive when using Ethernet or DMX, so we tried to minimize costs by using electric cables to create communication areas.

—Incidentally, Perfume’s project Perfume LIVE@Tokyo Dome “1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11” was also one of the Jury Selections in the Entertainment Division at the 15th Japan Media Arts Festival. Apart from the name of the work, the credits include the names 4nchor5 La6 and Rhizomatiks.

MANABE Yes, that’s correct. Incidentally, we were also involved in the production of the film Nike Music Shoe (a work of Jury Selections in the Entertainment Division at the 14th Festival) and of The Museum of Me (the Excellence Award in the Entertainment Division at the 15th Festival) as Rhizomatiks but not credited. We are not always satisfied with the fact that in some projects our names go unmentioned, even though we participated in them. As we are involved in a lot of collaborations, we have always had a hard time when we applied for the festival.

—A robotic arm appeared in the video trailer for The Museum of Me. Speaking of works using robot arms, a little later, there was also YASKAWA × Rhizomatiks × ELEVENPLAY, a Jury Selection work in the Entertainment Division at the 19th Festival in 2015. Was this something you were consciously working on at that time?

ISHIBASHI Yaskawa Electric made us an offer for its commemorative ceremony after seeing the music video for Yakushimaru Etsuko Metro Orchestra’s Boys, Come Back to Me, which we produced in 2011, the same year as The Museum of Me, and the event was held in 2015. By the time of the 19th Festival, I had already become aware of drones and was working on various ideas, including the use of drones in NHK’s Kohaku Uta Gassen in 2014, and the work 24 drones, which combined a group of drones with a dance performance by ELEVENPLAY, awarded as a Jury Selection for the 20th Festival.

MANABE We acquired a motion capture system around 2012, and since this made it possible to control a drone by tracking its position and orientation, we began to incorporate it into our stage productions. We also added a member who specialized in AR, and as a result the range of things we can do expanded even further.

—Going back a little bit, could you please tell us about your collaboration with SAKAMOTO Ryuichi, Sensing streams – invisible, inaudible, which won the Excellence Award in the Art Division at the 18th Festival in 2014?

MANABE This work was intended for presentation at the Sapporo International Art Festival,6 and the theme was “city and nature.” While communicating with Mr. SAKAMOTO, we learned that a team at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM] had measured the electrical potential of trees and converted this into sound, so we decided to develop an urban version of that, and to work with the electromagnetic waves used in information communication. Around that time, while working on the hardware side with drones, our interest in the software side shifted towards machine learning, and in this work, we tried to do something like finding patterns in the electromagnetic waves. However, the data was not very distinctive and so it was difficult. At that time, we could only perform simple rule-based recognition. We were still at the stage before we could deal with deep learning.

—Activities that span both the Art and Entertainment divisions could be considered a unique feature of Rhizomatiks. Is there anything you are especially conscious of in your activities?

MANABE I wasn’t conscious of anything in particular when we were making our works, so every year when it was time to apply, we would discuss what to submit and which division to submit it to.

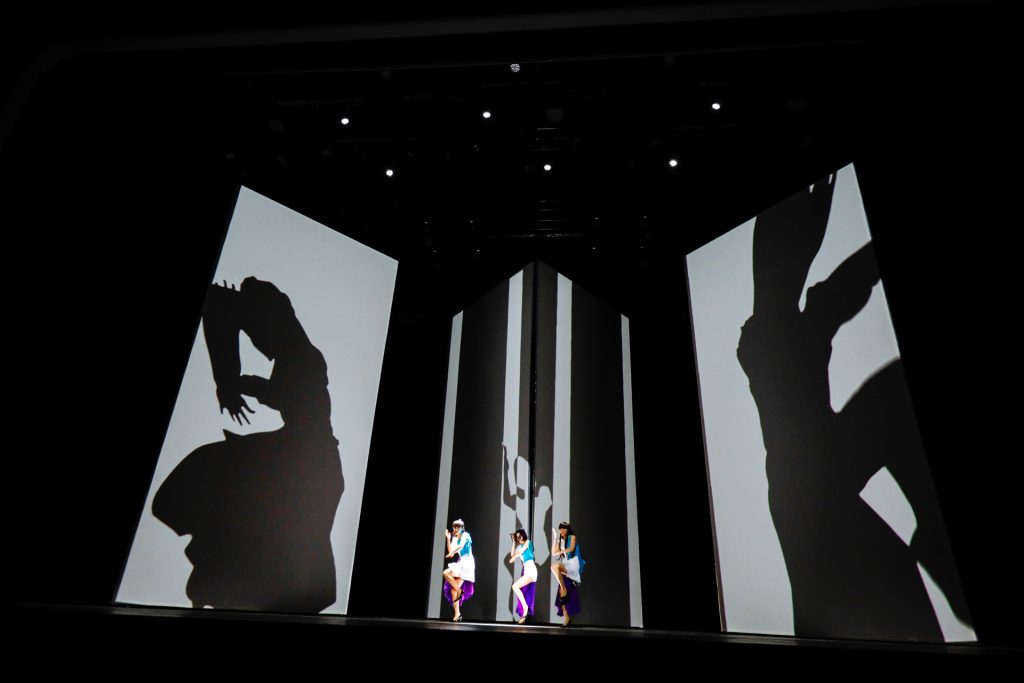

ISHIBASHI In this regard, the 22nd Festival (2019) was an interesting year. Two of our works received awards in two divisions, namely discrete figures won the Excellence Award in the Art Division and Perfume Technology presents “Reframe” won the Excellence Award in the Entertainment Division.

MANABE For both of these works, MIKIKO handled the direction and choreography, I did the tech planning, and Rhizomatiks took care of development and production, and they both had similar themes, such as dealing with drones and machine learning. However, discrete figures started from the motifs of mathematics and the body, so it was concept-oriented. Conversely, Perfume Technology presents “Reframe” was all about what the audience sees, rather than about the background of the work. The fact that the text was also minimal led to this separation. Nevertheless, the latter work was also very conceptual in that it reconstructed past data to create a new show. I don’t think it would have been out of place if it had been submitted to the Art Division. In my personal opinion, the Entertainment Division was the most interesting division to watch. There were other competitions that were subdivided, such as in the game division and the music video division, but in the Japan Media Arts Festival, everything was jumbled together, and the most talked about works in a given year or those that became social phenomena are selected as the representative works for the year in question. I think this was a good thing. On the other hand, from the perspective of an applicant, I had a feeling that the trend of award-winning works in the Art Division would change according to the lineup of the jury members, so when I submitted an entry, I would think about it while looking at the jury members. At the opinion exchange meeting, we introduced examples such as Ars Electronica, and emphasized that it would be better for us to consider the age, race, and gender diversity of the jury members. However, we didn’t create works for the purpose of winning awards, so we basically submitted works from a given year, as if it were an annual event, and for us that was the Media Arts Festival.

—What roles do the two of you play, either individually or as the Rhizomatiks team, in creating your works?

MANABE I am often the one who initiates the process. However, we keep making changes and listen to feedback from everyone as we go along, so as a result, in most cases we all work together from the concept stage.

ISHIBASHI For example, the rails for particles were designed by SAKAMOTO, a member of Rhizomatiks who specializes in architecture, but I was the one who suggested the very simple shape of a figure-8 spiral structure. At first, I had envisioned a more complex structure, but once it was decided to have the balls roll and the technical feasibility of the flashing lights and other features became clear, I decided that I wanted the balls to stand out and appear as if they were floating in the air. To achieve this, I thought it would be better to keep the structure very simple. Daito is very good at coming up with themes that trigger the creation process. He presents us with challenging lines that Rhizomatiks could reach if we worked a little harder, and I feel that if we can jump towards that goal, it would be a very good project.

MANABE I feel as if I am looking for a subject while considering the skills and resources of our members, to see if we can do something new. With the current members, we can do everything ourselves, including the system, content, and hardware. That is the interesting thing about Rhizomatiks, and I really enjoy searching for new themes.

—What are some of the technologies you would like to work on in the future, and what technologies are you currently interested in?

ISHIBASHI One thing I am interested in but have not yet been able to do is to use AI and machine learning to control machines and create movement patterns. This technology is being utilized in the industrial field, especially in cleaning robots, but I don’t think it has been widely used for the purpose of artistic expression yet.

MANABE That area seems to be a future challenge for Rhizomatiks, which focuses on both hardware and software. Currently, generative AI such as ChatGPT and Midjourney 7 are making various breakthroughs, and I have no doubt that these technologies will have an impact on the control of hardware in the future, as Mr. ISHIBASHI mentioned. Both ChatGPT and Midjourney are services that can be used by anyone, so if you just utilize them, you will end up competing to see who can create the most interesting content. But for us, we want to work not only on content creation but also on developing a mechanism or system. However, as with anything, even if we can do something interesting with a mechanism at first, we quickly move into the arena of content. Around 2010, openFrameworks 8 became popular, and with the release of Kinect, 9 interactive systems became easy for anyone to create. The number of creators increased, and since then interactive art has truly become a battle between contents. In many ways, this was a major turning point.

—Rhizomatiks is always looking forward to a time when its technology will be considered cutting-edge and when the mechanisms underlying this technology are fresh and interesting.

MANABE Yes, that’s true. I feel that if everyone is on the same playing field and it starts to become a battle over content, there is no point in Rhizomatiks taking part anymore.

—What would you like to say about the Japan Media Arts Festival?

ISHIBASHI I hope there will continue to be some kind of venue for media art presentations in the future. There aren’t many opportunities or places to present installations and media art performances. Also, at the Media Arts Festival, there were a number of manga and animation works that I was unfamiliar with, so I think there must have been people who, unlike me, came to the event to see manga and animation but came across art and entertainment works. I think it was a good opportunity for both of us. And this is especially true in the case of manga, which is a medium that reflects the times and the state of the world more strongly than media arts do. By looking around the four divisions as a whole, you can really get a good grasp of the current situation. At least, that’s how I felt as an audience.

MANABE In the past, many audience members were perplexed about how they should behave toward interactive art, but now everyone accepts it as a matter of course. Over the past 25 years, media arts have become generally recognized. Japan currently has more schools and faculties for media art than any other Asian country, and works are produced in many engineering faculties. For those of us who are involved in both art and entertainment, I think it is great that the base of media art has expanded.

notes

MANABE Daito

Co-director of Rhizomatiks and Abstract Engine Co., Ltd. Artist, Interaction Designer, Programmer, and DJ. Born in Tokyo in 1976. He graduated from the Department of Mathematics at the Tokyo University of Science, and the International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS). Established Rhizomatiks Co., Ltd. in 2006. He creates works by reinterpreting and combining familiar phenomena and materials from different perspectives. Focusing on the relationship and boundaries between analog and digital, real and virtual, he works in the fields of design, art, and entertainment.

ISHIBASHI Motoi

Co-director of Rhizomatiks and Abstract Engine Co., Ltd. Engineer and Artist. Born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1975. He graduated from the Department of Control Systems Engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and the International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS). Focusing on device production, he energetically engages in various activities such as numerous advertising projects, art productions, workshops, and music video productions.

Japan Media Arts Festival 1997–2022: 25 Years of Progress

The 25-year journey of the Japan Media Arts Festival, first held in 1997 and concluding in 2022. The book showcases the development of media arts, nurtured alongside the advancement of digital technology, and compiles the trajectory of its growth into an international festival, spanning over 800 pages. Publication date: March 31, 2023 Price: 5,000 yen (excluding tax) Size: B5 Cooperation: Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan Published by: The Computer Graphic Arts Society (CG-ARTS) https://www.cgarts.or.jp/archives/3599 (in Japanese)

*Interview date: December 15, 2022.

*URL links were confirmed on May 1, 2023.