TAKEMI Yoichiro

Starting with AKIRA (1988) in the late 1980s, the imagery of near-future cities depicted in science fiction animations such as GHOST IN THE SHELL (1995) and Metropolis (2001) has garnered significant interest overseas. German art curator Stefan RIEKELES has focused on the high-density background art of these animations as revelatory “landscapes.” So, together with David D’HEILLY, MYOKAN Hiroko and others, he has organized traveling exhibitions “Proto Anime Cut” (2011–2013) and “Anime Architecture” (2016–2020). In Japan, the exhibition “Cityscapes in Anime Background Art” is being held from June 2023 at the Yoshiro and Yoshio Taniguchi Museum of Architecture, Kanazawa, which is based on these two exhibitions and the exhibition “AKIRA: The Architecture of Neo Tokyo” (2022), he co-curated with Ms. MYOKAN, and includes new content. In a discussion with IGARASHI Taro, an architecture critic who was involved in the Kanazawa exhibition as a supervisor, and Mr. RIEKELES, we will consider what we can see now in the urban images drawn by creators from the late 1980s to the early 2000s.

—I would like to ask you about the relationship between Stefan RIEKELES and IGARASHI Taro. The current exhibition, “Cityscapes in Anime Background Art,” marks the triumphant return to Japan of a traveling exhibition curated by Mr. RIEKELES, and I understand that Mr. IGARASHI provided support from his architectural perspective for the exhibition in Kanazawa. Have you interacted with each other before?

RIEKELES The first animation and architecture project I was involved in was the “Proto Anime Cut” exhibition held in Berlin in 2011. Since that time, Mr. IGARASHI has been advising me on the texts related to the exhibited works and contributing to the publication of exhibition catalogs.

IGARASHI I had heard that it would be difficult to hold the exhibition in Japan due to the complicated rights of the materials to be exhibited, but that it would be possible to start in Europe. Fifteen years ago, I had sent only some texts, but for this current exhibition, I’m fully participating because the venue is a museum of architecture.

RIEKELES My first direct correspondence with Mr. IGARASHI was in 2008 when he wrote a recommendation letter for a residency at Tokyo Arts and Space (TOKAS). Thanks to him, I was able to obtain a very valuable residency opportunity at TOKAS.

—Mr. RIEKELES, I’ve learned that your research theme is media art and your area of expertise is not animation. What was your experience with Japanese animation?

RIEKELES I first came to Japan in 2005. I came to Japan as a team staff member in connection with the Goethe-Institut’s project for the year “Germany in Japan.” It was the beginning of my desire to stay in Japan for a longer period of time. I became interested in Japanese culture, especially Japanese gardens. Later, when I was staying in Kyoto for an extended period of time and studying with a Japanese garden expert, my friend David D’ HEILLY took a job with an anime exhibition at a museum in the United States and hired me as his assistant. I met OGURA Hiromasa1 for the first time through this job.

—Mr. OGURA is a key figure in the field of background art, having served as art director on many of Director OSHII Mamoru’s films.

RIEKELES I visited Mr. OGURA’s studio and saw the original background art for GHOST IN THE SHELL spread out on his desk. It was incredible craftsmanship. At that point, I had not yet seen the film, but in front of the original, I intuited its value. And importantly, the foundation of my interest was in media art critique, where I saw the original artwork as a fragmented remnant of the artistic process. Mr. OGURA’s artwork is not high art in the sense of being placed in a museum. The context must be made clear to the audience. It was a big challenge for me as a curator, but I felt strongly that I had to exhibit these works in a museum.

Mr. OGURA’s first reaction, however, was, “Outrageous, I don’t want to show such a picture.” He said, “This is not art. The film is the final work. The film is the art.” After many people’s cooperation, the exhibition was finally realized in 2011. Mr. OGURA came to our opening in Berlin, Germany. After we looked around the exhibition together, he said to me, “Okay, Stefan. I understand.”

—Mr. IGARASHI, you specialize in architectural critique, but when did you start critiquing animation?

IGARASHI Do you remember the large number of “Evangelion books” published after Neon Genesis Evangelion broke out in 1995? I was a graduate student at the time and was involved in several of those books. In fact, the first book with my name on the spine is my critique on Evangelion.2 Of course, my research continued to focus on architecture, but I have continued to write about how architecture and cities are depicted in animation, including contributing essays to the exhibitions of Innocence (2004) and Steamboy (2004) at the Mori Urban Institute for the Future in Roppongi Hills. However, I had not seen the original drawings properly, so I was surprised to see them this time at the exhibition. I could see how they were drawn, even down to the movements of their hands. I believe it’s an exhibition that won’t make sense unless you see the original artworks on site.

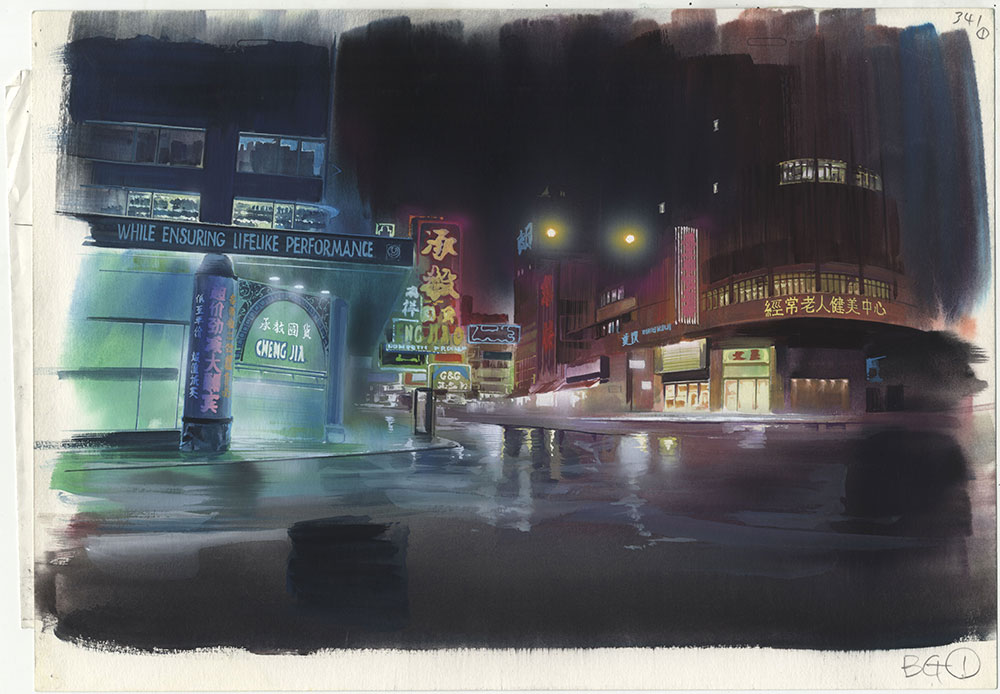

—Let’s list the works exhibited in Kanazawa in order of release year (with the names of the art directors): AKIRA in 1988 (Art Director: MIZUTANI Toshiharu),3 Mobile Police Patlabor: The Movie in 1989 (Art Director: OGURA Hiromasa), Mobile Police Patlabor2: the Movie in 1993 (Art Director: OGURA Hiromasa), GHOST IN THE SHELL in 1995 (Art Director: OGURA Hiromasa), Metropolis in 2001 (Art Director: KUSAMORI Shuichi),4 and Tekkonkinkreet in 2006 (Art Director: KIMURA Shinji).5 These works were produced over a period of about 20 years from the end of the 1980s. What significance does this chronological bracketing hold?

RIEKELES The works were created during a transitional period when animation adopted a digital workflow. An important point for me is the change in media. I am attracted to artwork (original art) that reflects change. Although we were not able to show anything related to Evangelion in this exhibition, the last chapter of the book Anime Architecture: Production Process of Masterpiece Background Art (Graphic-sha, 2021), which is connected to the previous exhibition, features Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance (2009, Art Directors: KATO Hiroshi,6 KUSHIDA Tatsuya).7 The layout pieces of TOKYO-3, drawn by Director ANNO Hideaki in pencil on paper, are included. There is no traditional hand-drawn background artwork in this work, instead, every step is executed digitally from Director ANNO’s layout onwards. Therefore, certain areas of the layout have instructions that simply read “3DCG” with blank spaces.8 I believe this serves as a symbolic picture to understand the changing nature of production technology.

—Mr. IGARASHI, how do you view the works of this period from your perspective?

IGARASHI Many of the works we feature are set in Tokyo, but they were created during a time when Tokyo was truly vibrant. From the late 80s through the 90s, there was an economic bubble, a peculiar situation even by global standards. Intense scrap-and-build activities took place, similar to present-day scenarios in China or Dubai in the Middle East. I feel that it was no coincidence that anime depicting urban areas such as Patlabor and AKIRA emerged during that era.

What is more common is the urge to destroy cities. Although Japan is a country that has basically been remained free of warfare since its defeat in the Pacific War, animation and tokusatsu (live-action films with special effects) often portray scenes of cities being destroyed relentlessly. In both Patlabor and AKIRA, the filmmakers exhibit a desire to destroy Tokyo. As this shifted to the generation of HOSODA Mamoru (born in 1967) and SHINKAI Makoto (born in 1973), who followed directors OSHII Mamoru (born in 1951) and OTOMO Katsuhiro (born in 1954), the dynamic transformed as the city’s energy lessened. In HOSODA’s The Boy and the Beast (2015), the Shibuya area is depicted with intricately detailed background art, and in the climax, TANGE Kenzo’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium becomes the setting for a catastrophe, yet the attitude towards Tokyo differs. SHINKAI’s series of films portray Tokyo’s beauty, and the shadow of animosity is no longer present.

RIEKELES Even if Tokyo has changed since the bubble economy era, the Tokyo depicted by SHINKAI remains incredibly beautiful. Why is that? I think OSHII doesn’t make a definitive positive or negative judgement about Tokyo. Instead, he portrays an ambivalent attitude towards Tokyo in his works.

IGARASHI There might be a reason for this within the structure of the narrative itself. SHINKAI is sometimes classified with a genre called “sekai-kei.”9 The structure directly links the personal relationship between “me,” the protagonist, and “her,” as well as a significant event like a global crisis. In other words, society is absent from sekai-kei. To highlight the contrast between the mundane and the larger context, the setting where she and I exist is depicted with heightened beauty. On the contrary, OSHII exhibits a strong interest in societal dynamics and aims to capture society’s ambivalent aspects.

RIEKELES I understand that each director’s perspective has influenced the style of the background art. This brings to mind the comments shared by KUSAMORI Shuichi and KIMURA Shinji at the exhibition forum. Despite requests from various production companies for them to create backgrounds in the SHINKAI style, they decline, stating that it’s not their artistic approach.

Particularly, I find that the architectural art presented by Mr. KUSAMORI has a strong connection to society. There’s a discernible awareness that society finds its reflection in the constructed environment. This very reason is why it harmonizes well with OSHII’s works.

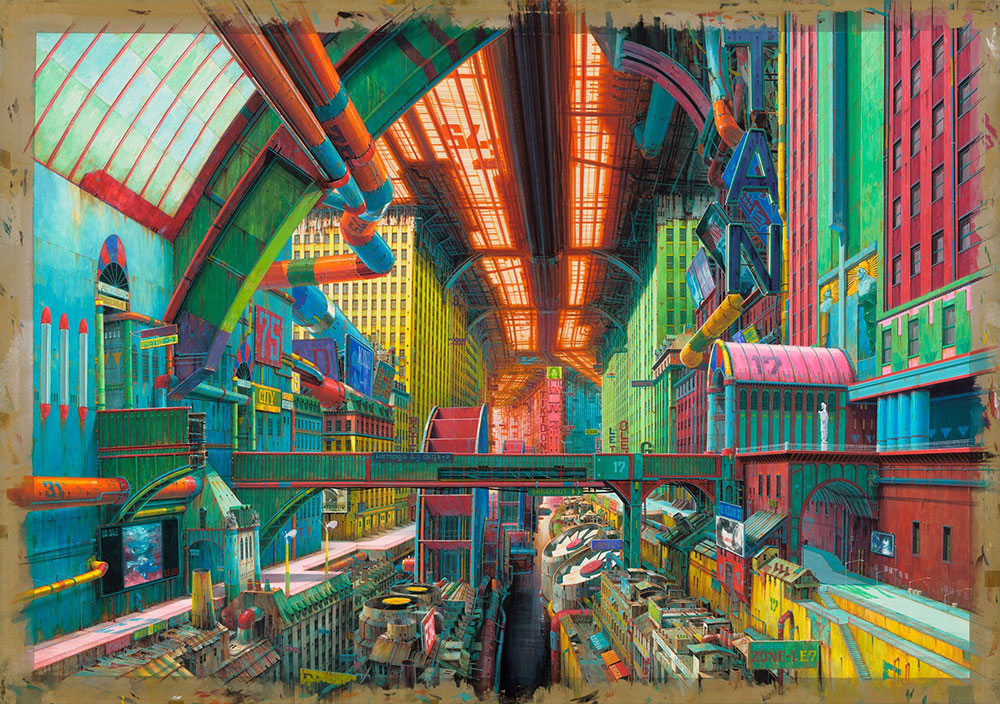

IGARASHI I agree. In this exhibition, Mr. KUSAMORI’s creation Metropolis is featured, and it truly exemplifies the expression of society through background art. Metropolis vertically dissects the urban landscape, spanning from the ground to the basement. The skyscraper Ziggurat embodies an architectural fusion of futurism and SCHUITEN’s urban aesthetics. At the ground level, the space adopts a postmodern style, maintaining classical elements within a grid framework. Additionally, in the basement, a vividly colored space is inhabited by robots, organized into three distinct zones.

RIEKELES In Metropolis, the high-rise world was created using computer graphics, while the low-rise world was depicted using hand-drawn background art to emphasize the structure of social conflict. It was a hybrid of traditional paper-based backgrounds and digital workflow.

IGARASHI During the forum featuring Mr. KIMURA and Mr. KUSAMORI, the discussion also touched on Blade Runner (1982). Mr. KUSAMORI’s enthusiasm for the film was notably strong, leading me to perceive their background art as a direct product of Blade Runner. In order to capture Los Angeles in its 2019 setting, they ingeniously melded Oriental imagery with neon lights and advertisements, creating an innovative urban image. It was intriguing to witness how historical structures, like the Union Station with its 1930s aesthetics, harmoniously coexist with Syd MEAD’s futuristic designs.

RIEKELES The imagery of juxtaposed old and new cityscapes and the embrace of multiculturalism undeniably exerted a tremendous influence, not only on subsequent live-action films but also on animated near-future cities. Incidentally, while Blade Runner stands as a significant Hollywood film, certain concerns arise when it comes to the storytelling in the animated films showcased in this exhibition. One such concern is the absence of a protagonist with a commanding presence. Hollywood and Disney animations are characterized by the distinct establishment of protagonists, a clear purpose, an antagonist, and a well-defined conflict.

IGARASHI In the Mobile Police Patlabor: The Movie, even the mastermind behind the incident, HOBA Eiichi, exits the story quite early, leaving the remaining characters to navigate through the chaos within Tokyo.

RIEKELES AKIRA also presents a challenge in capturing the central protagonist. The boy named Akira, who holds the title role, only appear at the end of the film. The characters propelling the narrative are Tetsuo and Kaneda, yet several other significant characters and multiple storylines run concurrently. Identifying a clear central character proves to be a challenge.

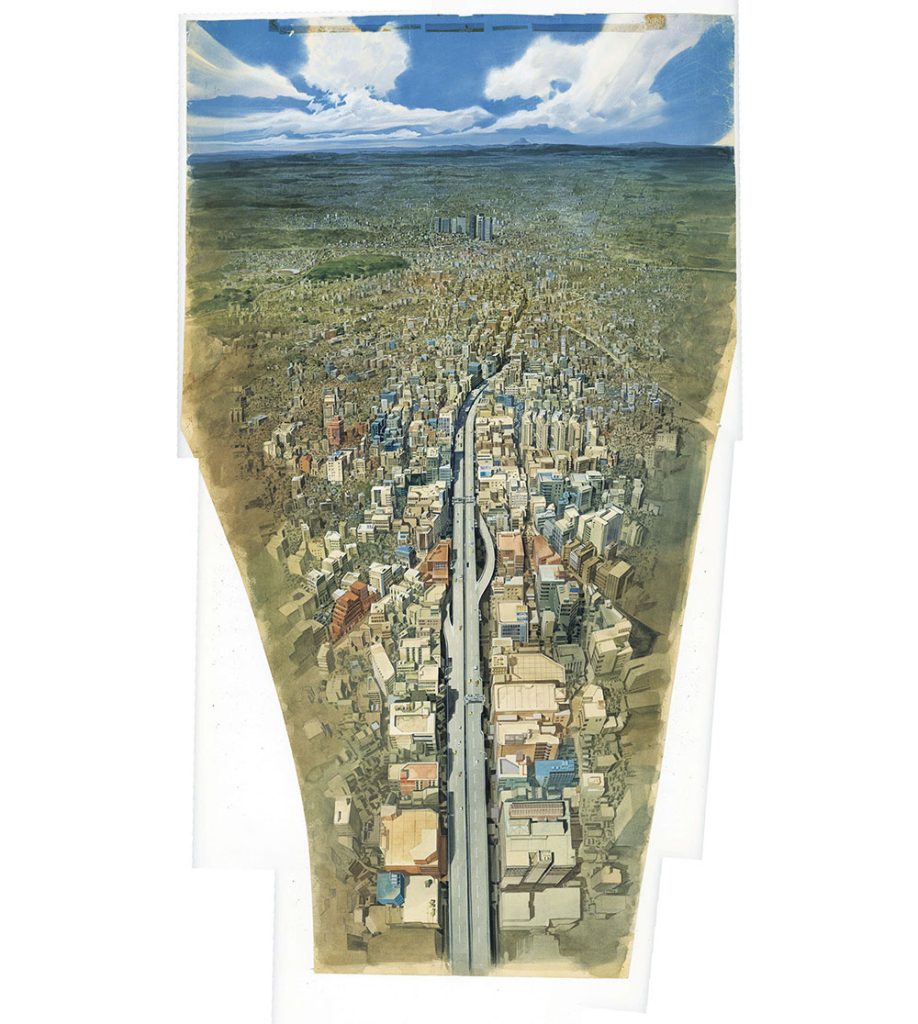

IGARASHI I think that in AKIRA, Neo-Tokyo, a sprawling megalopolis on Tokyo Bay set in 2019 against the backdrop of the upcoming Olympics, takes on a role akin to the film’s main character, given its ensemble drama nature. Since Blade Runner, there has been a significant trend wherein cities, originally relegated to the backgrounds, are now portrayed as prominent characters in films. When discussing the portrayal of cities in AKIRA, it’s imperative to acknowledge OTOMO Katsuhiro as the manga artist. His background art exhibited an unprecedented level of intricacy, a density never before seen in Japanese manga. This very density was seamlessly translated onto the screen, making yet another groundbreaking achievement.

—OTOMO hails from Miyagi Prefecture. He mentions that the most lasting impression upon arriving in Tokyo was not the towering skyscrapers in the heart of the city, but rather the metropolitan elevated highway road running overhead.10 This anecdote could provide insight into how OTOMO visually perceives the city.

IGARASHI In AKIRA, there is a scene in the first half of the story where KANEDA and his friends ride motorcycles on the highway. The latter half of the film portrays the entire city, along with its highways, disintegrating. OTOMO intricately illustrates the destruction of architecture. Similarly, I observed in the manga Domu (Futabasha, 1983) that portraying the depiction of architecture proves to be an effective means of visualizing invisible psychic powers.

RIEKELES OSHII’s work diverges in its approach to depicting city destruction. For him, mere physical devastation is an overly simplistic resolution. Blowing up cities does not eliminate social problems.

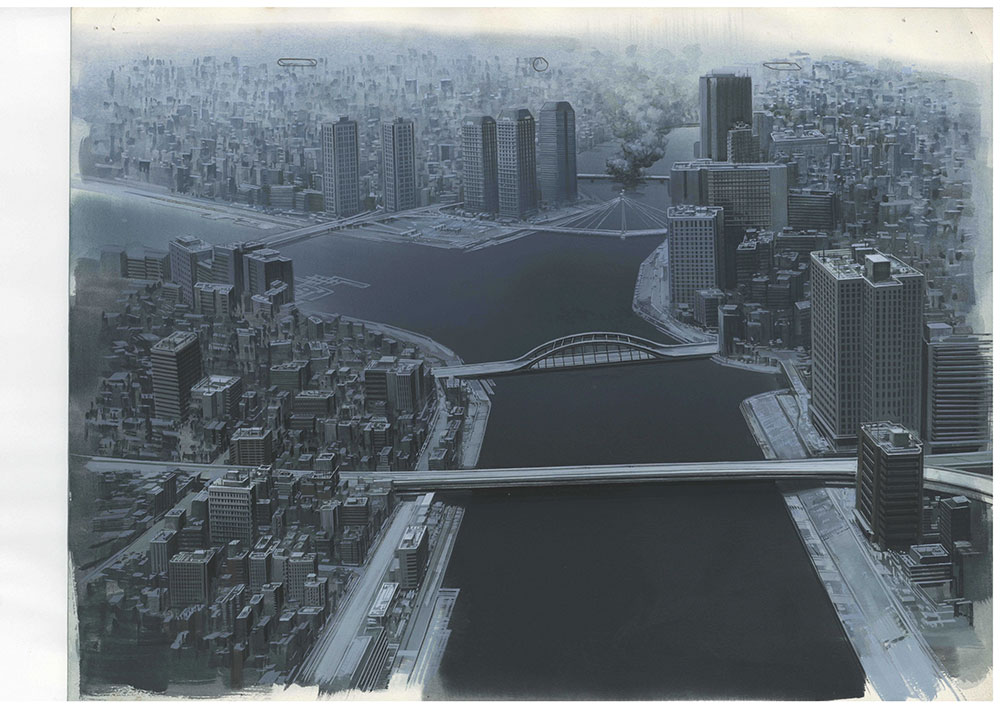

IGARASHI Mobile Police Patlabor 2: the Movie was created two years before the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, but it prophetically depicted how striking the information and transportation infrastructure would result in a dysfunctional, pseudo-war situation. If someone really intended to impact Tokyo significantly, possessing a cartographic imagination would be more crucial than psychic powers.

RIEKELES Exactly. Neo-Tokyo in AKIRA is like a simulation of a city that exists only as an image. In the case of a simulation, it is important to destroy it completely, but if it exists in reality as depicted by OSHII, it is enough to attack it with pinpoint accuracy.

—It seems that the key to creating a new image of a near-future city through animation is what Tokyo looks like today and how its creators perceive it. How do you see Tokyo today?

IGARASHI I’ve had the opportunity to interview OSHII several times, and he says he has no interest in anything in Tokyo today.11 There was a sense of anticipation at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that the city would be transformed by a tremendous force. However, the tremendous energy of the new city was unfortunately not expressed in this Olympics. As Mr. KUSAMORI agreed,12 the collapse of Zaha HADID’s proposal for the New National Stadium13 is symbolic. TANGE Kenzo’s stadium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics was of world-class architecture. We could not see such a standard of architecture at the Olympics 2020.

RIEKELES I have been visiting Tokyo for 15 years, and every year I return, there is a new building somewhere. Hikarie and Shibuya Scramble Square, and more… However, they all look the same. Waterfront developments and buildings from the 80s carried a distinct message, a novel narrative. Yet, it appears that today’s Tokyo lacks that same sense.

IGARASHI I agree. One architectural historian has described it as a “business suit building.” While high-spec, it lacks intrigue. Rem KOOLHAAS also noted the same sentiment. Simply put, Tokyo has become conservative. Have you seen Shin Godzilla (2016)? In the film, Godzilla encounters no novel attractions in today’s Tokyo. Instead of making its way to Tokyo SKYTREE, Godzilla demolishes the business suit buildings. In the final scene, Godzilla transforms into a massive statue of itself, effectively becoming a Tokyo landmark, diverging from its original return to the sea.

RIEKELES It is a very unique ending for urbanism. On the other hand, I have high expectations for Japan’s futuristic cities. I visited several local cities during my stay in Japan this time, and it was an interesting experience. For example, in Ono City, Fukui Prefecture, almost all residents there were elderly people that I thought I was the youngest person in the city. Japan’s unique population balance is more apparent in rural areas than in Tokyo. And as the population continues to decline, specific changes will occur in rural areas in the next few years. People will disappear, so scrap-and-build cannot be repeated as in the past. I feel that a new urban style will emerge in rural Japan. At that time, another monster that is not Godzilla may be on its way to destroy it.

—Then it is also suggestive that this exhibition is being held in Kanazawa and not in Tokyo.

RIEKELES Many people from Tokyo are expected to come and see the exhibition. It will be a wonderful opportunity for the audience to leave Tokyo, see how the image of their city, where they reside, is being destroyed and reconstructed, and then bring back new thoughts about the city.

notes

IGARASHI Taro

Born in 1967 in Paris, France. Architecture Critic. Professor at Graduate School of Tohoku University since 2009. Faculty at Sendai School of Design since 2010. Artistic Director for Aichi Triennale 2013. Commissioner of the Japan Pavilion at 11th Venice Biennale of Architecture. His publications include: Owari no kenchiku/Hajimari no kenchiku (Architecture of the end/Architecture of the beginning) (INAX Publishing, 2001); 3.11/After (Supervision, LIXIL Publishing, 2012).

Stefan RIEKELES

Born in 1976. Curator. Project manager and curator of the art and digital culture festival Transmediale (Berlin) from 2002–2009. He organized the traveling exhibitions “Proto Anime Cut” (2011–2013) and “Anime Architecture” (2016–2020), both focused on the theme of animation and architecture. Founding member of Les Jardins des Pilotes, an organization that conducts exhibitions and festivals.

information

Cityscapes in Anime Background Art

Exhibition period: June 17 (Sat.)–November 19 (Sun.), 2023

Venue: Yoshiro and Yoshio Taniguchi Museum of Architecture, Kanazawa

Supervised by: IGARASHI Taro (Professor, Graduate School of Engineering, Tohoku University)

Curated by: Stefan RIEKELES, MYOKAN Hiroko, Yoshiro and Yoshio Taniguchi Museum of Architecture, Kanazawa

https://www.kanazawa-museum.jp/architecture/english/index.html

Translation: SHIGENO Kae

*Interview date: June 29, 2023.

*URL links are confirmed on September 14, 2023.