ODAGIRI Hiroshi

The word “manga” may conjure up images of “story manga,” in which a narrative story is told through pictures and speech bubbles in divided panels. However, dictionaries list “caricature” as another meaning. Manga was being established in a form different from today’s manga amid an influx of Western culture from the end of the Edo Period to the Meiji Era. ISHII Hakutei was actively involved in the formation of manga in a field where art and journalism overlap. This article will discuss the history of manga in Japan, tracing his activities as a creator of manga, in addition to woodcut printing and yoga Western-style painting, also his writing as an art critic.

MIYAUCHI Yusuke’s Kakushite kanojo wa utage de kataru: Meiji Tanbiha aesthetic school mystery book (Gentosha), released in early 2022, is a series of mystery stories about a group of young painters and literary figures, who gather at the “Pan no kai,” an aesthetic school art circle that actually existed at the end of the Meiji Era, engaged in a guessing game as following the format of Isaac Asimov’s The Black Widowers, a classic armchair detective story. This book, narrated by KINOSHITA Mokutaro, a medical student who later became known as a detective novelist, is not just a well-written mystery, but also a story about the youth of the pioneers of modern Japanese literature and art.

The Pan-no-kai was a private exchange group founded in 1908 (Meiji 41) by artists and literary figures such as ISHII Hakutei, KINOSHITA Mokutaro, YAMAMOTO Kanae, MORITA Tsunetomo, and KITAHARA Hakushu. It began when people involved with the art magazine Hosun,1 which ISHII, YAMAMOTO, and MORITA had launched the previous year, and KINOSHITA, KITAHARA, and others who had worked for Subaru hit it off. At the time, Japan was in the process of establishing a modern academic system and media environment including publishing. At the same time, the latest trends in European culture were continually being introduced to the country. Literature and art as institutions were still in the construction phase.

Among the characters in this series of stories, those involved with Hosun,2 especially ISHII Hakutei, had much to do with the development of the concept of manga in Japan. This article examines the relationship between Hakutei and the concept of manga in the Meiji Era.

Today, “manga” in Japan refers almost exclusively to “story manga” published in manga magazines. In the postwar period until around the 1970s, however, the nuances of the word included caricatures and illustrative expressions.3 In the early 20th century in Japan, when the format and idea of “story manga” did not yet exist, “manga” was almost completely unrelated to this current usage.

It is said that IMAIZUMI Ippyo was the person who first used the word “manga” in Japan to refer to the modern visual expression that has led to the present-day manga. He, a nephew of FUKUZAWA Yukichi, was in charge of the manga section of Jiji Shimpo, the newspaper that FUKUZAWA founded.4 This suggests that the word “manga” in the Meiji Era arose from the need for a term to refer to caricatures and illustrations in newspapers as part of the process of transplanting Western news reporting and publishing culture.

But according to current understanding of manga history, the first person to bring modern Western caricatures and manga to Japan was Charles WIRGMAN, an English painter who came to Japan in 1857 (Ansei 4) as a resident correspondent for the British newspaper the Illustrated London News.5 WIRGMAN published the caricature magazine JAPAN PUNCH for English-language readers living in Yokohama’s foreign district, where he lived. This magazine is regarded as the first manga magazine published in Japan. WIRGMAN was also a teacher for Western-style painters from the end of the Edo Period to the Meiji Restoration period.6 The period from the end of the Edo Period to the Meiji Era was a time when Japanese society was actively trying to import and transplant Western civilization. The pioneers of Western painting in Japan, such as GOSEDA Yoshimatsu and TAKAHASHI Yuichi, who studied under WIRGMAN. That was one of the pioneering examples of the national process of transplanting “Western art as culture and institution.”7

As a result of the historical transformation of the concept of manga as mentioned above, manga as popular culture and art as a fine art are now considered completely different, sometimes even in opposition to each other.8 When we return to the presence of WIRGMAN, we cannot help but feel a certain bewilderment at the emergence of this Englishman as the founder of both modern manga and Western art in Japan.

In his 2003 essay, “‘Manga’ gainen no jusoka katei–kinsei kara kindai ni okeru–” (The layering process of the concept of “manga”: From the early modern to modern periods),”9 manga researcher MIYAMOTO Hirohito points out that in Japan during the Meiji Era, many young artists, including those who had studied abroad, such as IMAIZUMI Ippyo, became interested in painting under the influence of Western art and were involved with the production of manga for newspapers and magazines. MIYAMOTO points out that the transplantation of Western manga was not only from the aspects of journalism and publishing, but also from the line of art. He also sees the formation of the new school in the Japanese Western-style painting world, including KURODA Seiki as a distant cause of this influence of Western art on manga. Here I will discuss the history of manga as an “impure” area where art and journalism overlap, as MIYAMOTO calls it, through the work of ISHII Hakutei, who is considered to have been more specifically involved in to form manga from the art side.

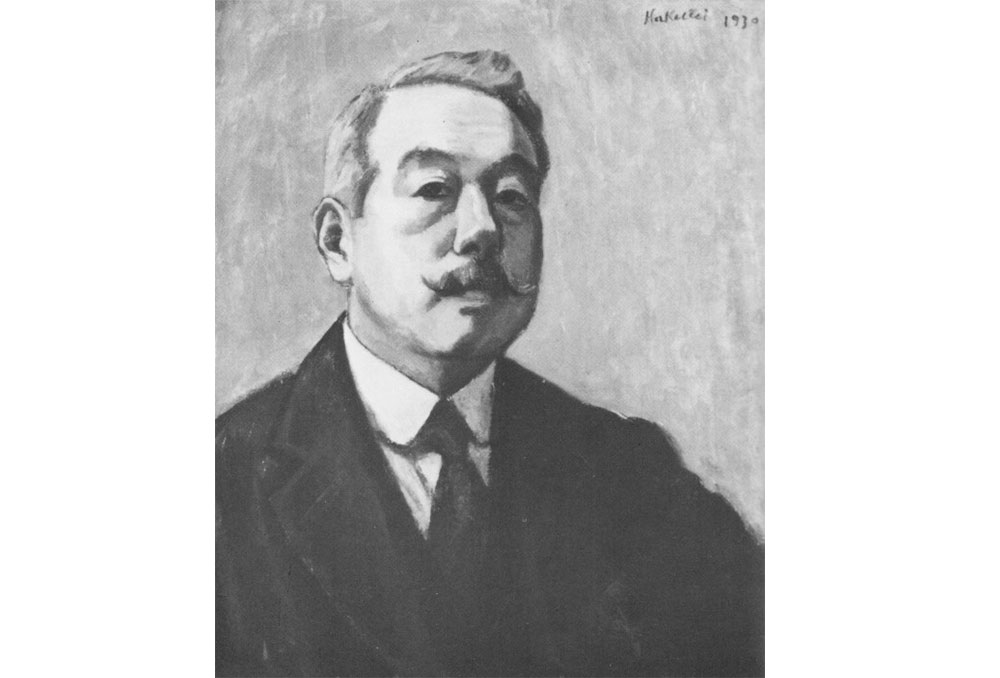

There are several reasons why I have chosen ISHII Hakutei as this essay’s focal person. First of all, he often discussed manga in his essays and writings as an art critic, including in a series of articles titled “Honcho manga shi” (History of Japanese Cartoon) 10 in the art criticism magazine Chuo Bijutsu 11 from 1918 (Taisho 7), which preceded HOSOKIBARA Seiki’s Nihon manga shi (A history of Japanese manga) 12 published in 1924 (Taisho 13), known as the first work with “history of manga” in its title. In addition, Hakutei himself was recognized as a manga artist 13 as he published his manga works not only in Hosun but in magazines such as Tobae and Sunday. Later, when he participated in the establishment of the Nika Association, an art organization founded to compete with the Nitten, a state-run public art exhibition, he also established a manga section as part of the open call exhibition. In other words, ISHII Hakutei was actively involved in the Japanese art world during the Meiji and Taisho eras, both as a theorist and as a manga artist, from a very early stage.

ISHII Hakutei, real name ISHII Mankichi, was born in 1882 (Meiji 15), the son of nihonga Japanese-style painter ISHII Teiko, when Ernest FENOLLOSA gave a lecture titled “Bijutsu Shinsetsu” (The true theory of art) at the Ryuchi-kai, and the concept of Japanese art became autonomous.14 He became familiar with painting under his father’s guidance from childhood. When his father lost his job at the Printing Bureau of the Ministry of Finance in 1892 (Meiji 25), he began to exhibit his works at the Japan Art Association and Seinen Kaiga Kyoshinkai (the Young Artists’ Exhibition) while working as an apprentice engraver at the Printing Bureau. In 1897 (Meiji 30), after the death of his father, he became a student of ASAI Chu and learned Western painting from him. In 1900 (Meiji 33), he joined the Musei-kai group whose members included YUKI Somei, playing a role in the new nihonga Japanese-style painting movement. As to yoga Western-style painting, he joined the Taiheiyo Art Association in 1902 (Meiji 35).

In 1904 (Meiji 37), he left the Printing Bureau to join Chuo Newspapers and entered the Western-style painting department of the Tokyo Fine Arts School (today’s Tokyo University of the Arts), where he was taught by KURODA Seiki and FUJISHIMA Takeji, among others. But he left both the newspaper job and his studies because he suffered from an eye disease. Relying on his sister in Osaka to recuperate, he began publishing poems and illustrations in Myojo, a literary magazine founded by YOSANO Tekkan in 1900 (Meiji 33).

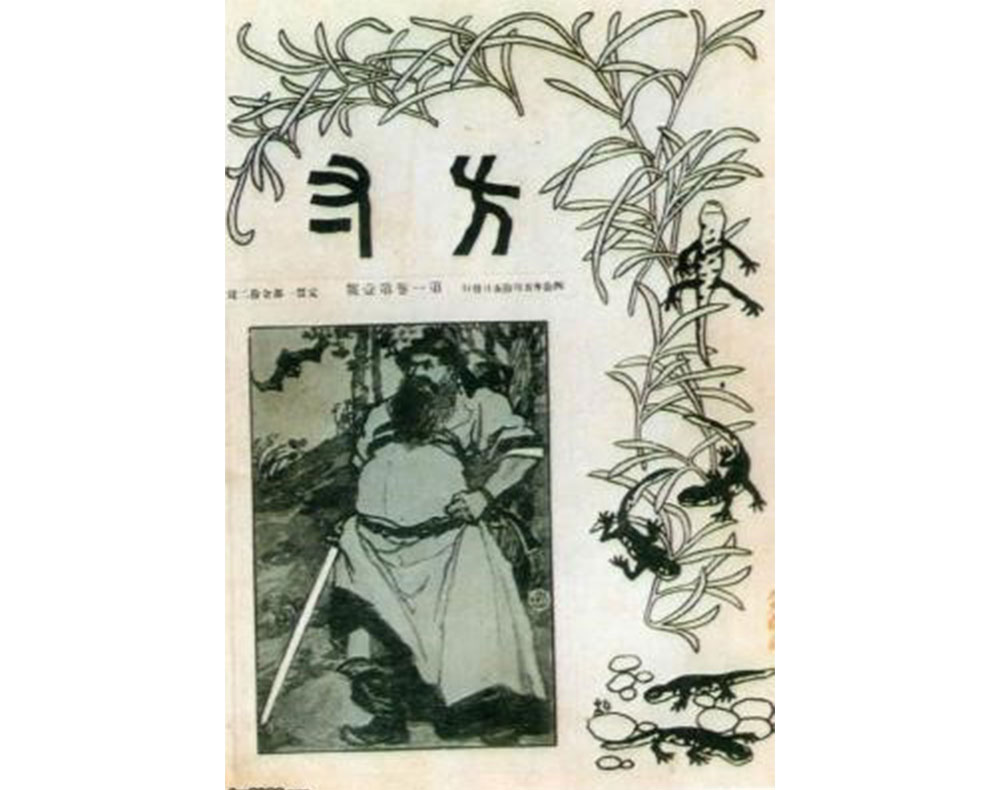

After recovering to some extent from his illness, he returned to Tokyo and launched Hosun in 1907 (Meiji 40) with YAMAMOTO Kanae and MORITA Tsunetomo, whom he had met at the Tokyo Fine Arts School.

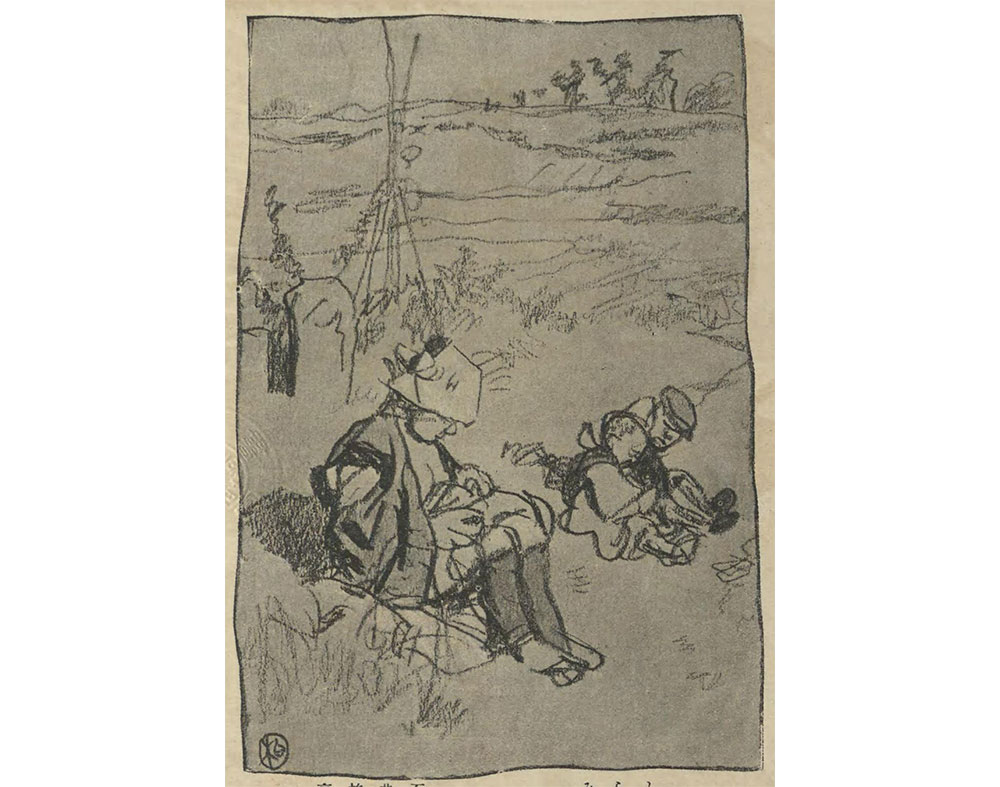

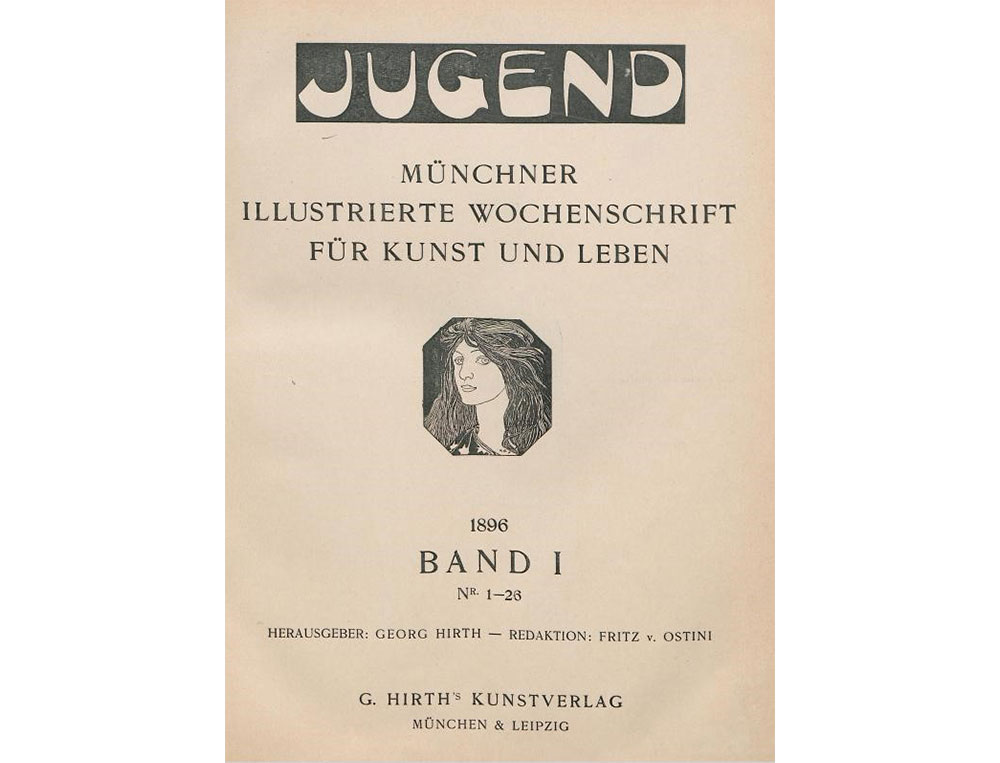

Today, this magazine is often recognized as a pioneer of the creative printmaking movement,15 but the actual pages and Hakutei’s own recollections suggest that the Hosun coterie considered this magazine a manga magazine. In particular, ISHII Hakutei clearly wrote in his Hakutei Jiden (The autobiography of Hakutei) published in 1971, “The model for Hosun was the German Jugend, the French Cocolico, and other manga magazines.”16 There is no doubt that he associated his activities in Hosun with manga.

The creative printmaking movement was an art movement that asserted the value of “prints” as a “reproduction art,” where the creator was responsible for all processes of the work and advocated “self-drawing, self-engraving, and self-printing” in contrast to the division of labor in traditional woodblock printing until the early modern period, such as ukiyo-e. At least Hakutei and others who pioneered this movement saw their expression there not just a movement of print but also as manga. So, what is “manga” there? I mean, what is “manga” in this context?

As an art critic and researcher, ISHII Hakutei specifically discussed what manga means in Western art in several books intended to introduce Western art to Japanese readers, such as Seiyo Bijutsu Ron (Western art theory) 17 and Bijutsu no Joshiki (Common sense of art).18

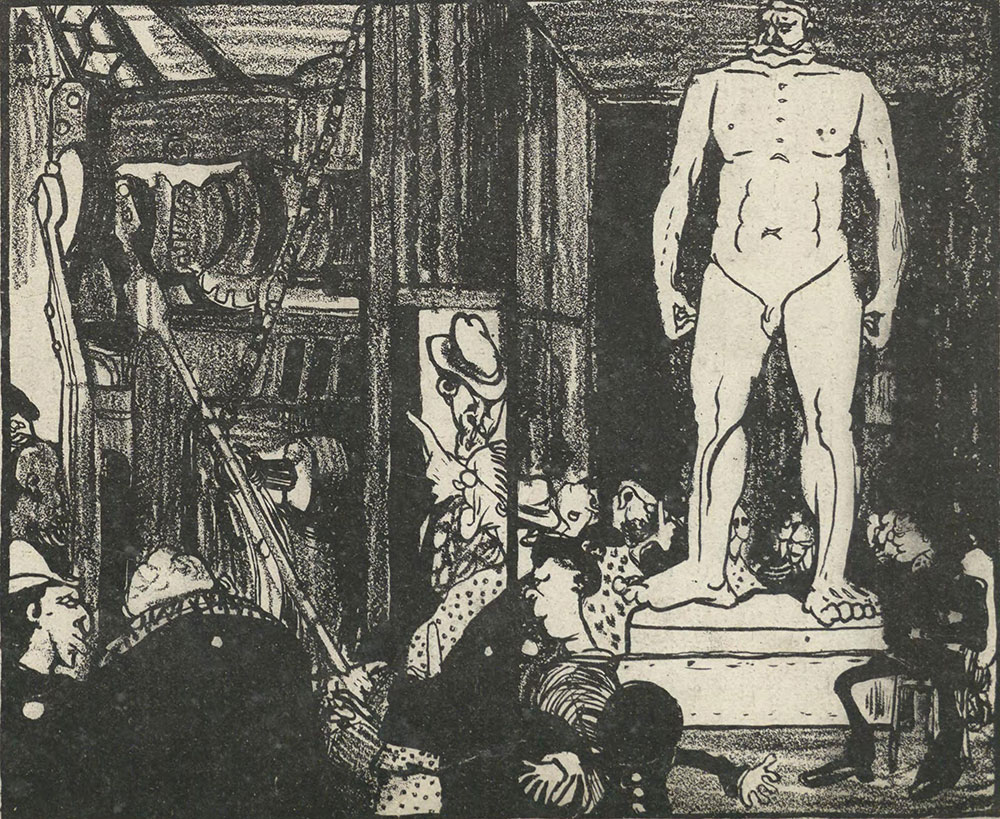

For example, in his Seiyo Bijutsu Ron (Western art theory), he wrote, “In teaching illustrations, we must also talk about manga,” and he positioned manga as something related to illustrations. He then goes on to cite a number of examples of prominent European caricaturists, including HOGARTH, ROWLANDSON, and CRUICKSHANK in Britain, as well as GOYA in Spain and DAUMIER and LAUTREC in France, whose works would not be considered “cartoons” or even “caricatures” in the current view of manga comics.19 In other words, Hakutei refers to a specific area within the European pictorial tradition as manga, and this area does not necessarily correspond to what we call caricature today.20

The dictionary definition of the word “manga” may primarily mean “a picture drawn with a simple and light touch, mainly in the sense of humor, exaggeration, satire, or nonsense,”21 and is often used as an equivalent of the English word “caricature,” perhaps because it reflects the image of “manga in journalism” since WIRGMAN.

However, at least for Hakutei and his contemporaries in 1907 (Meiji 40), manga was not something that could be equated with journalistic satire.

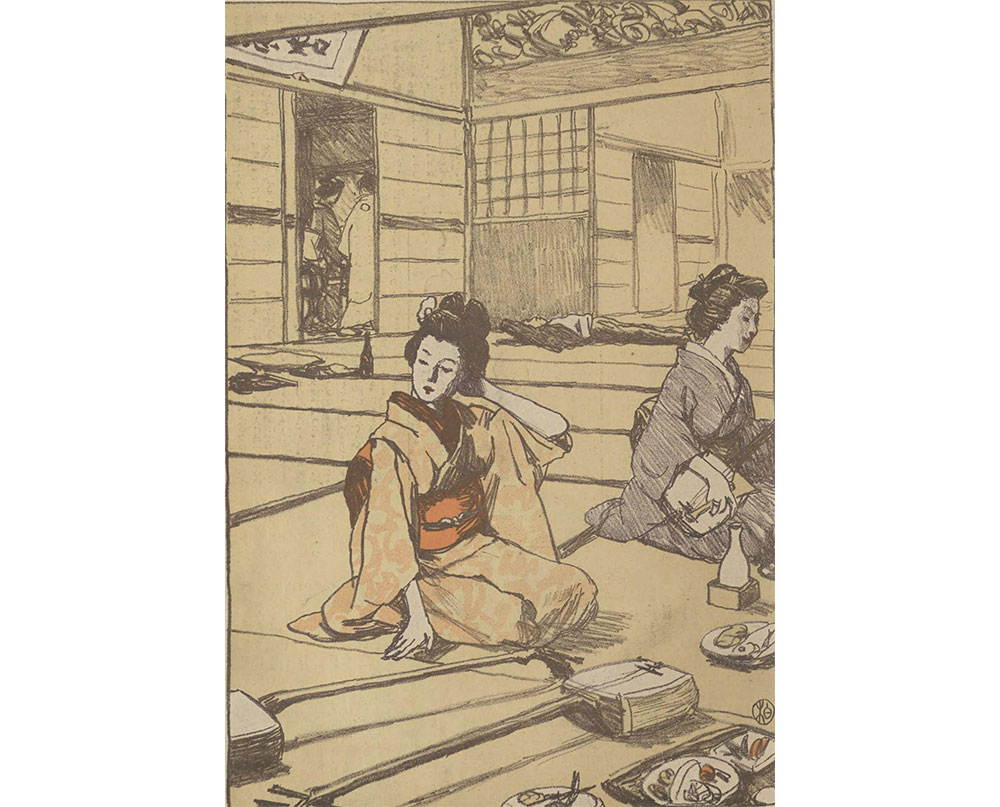

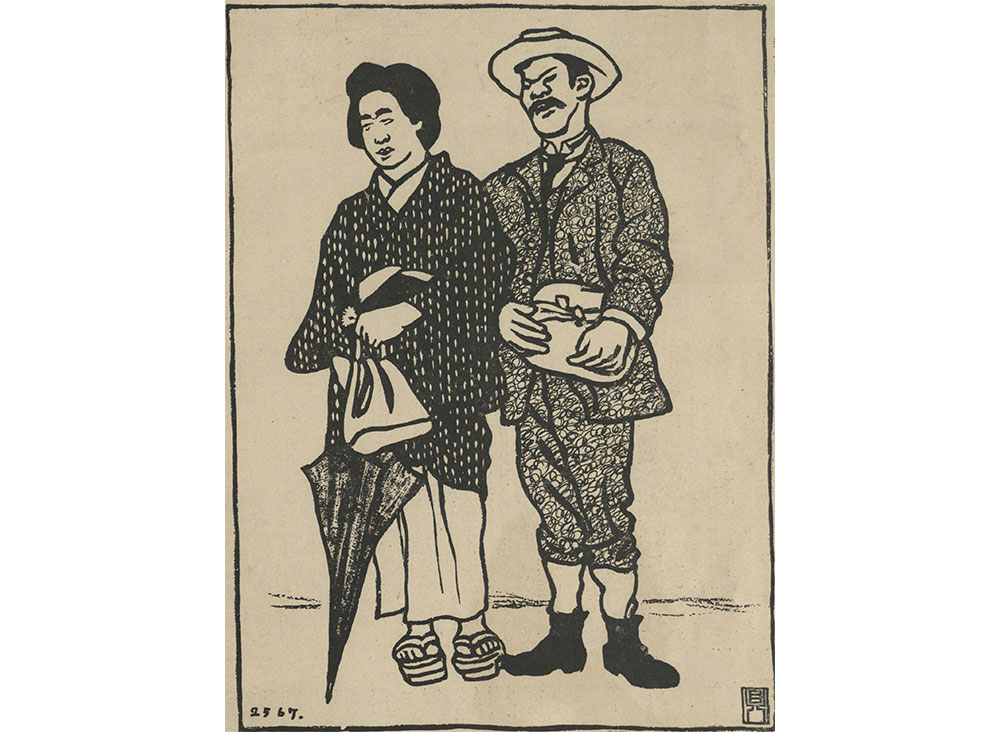

In the name of “manga,” I try to encompass a fairly broad range of paintings. By my own definition, “manga” is not necessarily limited to clownish or satirical works, as is usually thought of. Nor does it mean what is meant by Hokusai Manga. In a nutshell, it refers not to wearing a kamishimo formal dress and not being bound by rules, but mainly indulging in free observation and the drawing of human life. Even non-human creatures can qualify comics if they are given human sentiments.

This is the definition of “manga” in the first installment 22 of his “Honcho manga shi” (History of Japanese Cartoon) serialized in Chuo Bijutsu. But while we know that he did not require gags and satire to define “manga,” the actual meaning of “manga” as “manga that indulges in free observation and drawing of human life” is still somewhat unclear. Rather, this description is of such a nature that when contrasted with Hakutei’s understanding of “manga” in the West in Seiyo Bijutsu Ron (Western art theory), which I mentioned earlier, it becomes clear that it may refer to a kind of genre painting in terms of subject matter.

When ISHII Hakutei began his career as an art critic at the beginning of the 20th century,23 Japanese art was not yet established as a culture or institution as it is today. Also in Europe, the methodological development and systemization of art history as an academic discipline had not yet been established. Heinrich WÖLFFLIN, who is credited with establishing the study of art history as a “study of form,” published his book Bijutsu shi no kiso gainen (Principles of Art History) in 1915 (Taisho 4). At that time, Western art history as systematized and formulated in the form we know it today did not yet exist. Conversely, it was young painters and literary scholars of this period who, despite the time difference, enjoyed knowledge and the latest information on European art at a time when art history was about to be established as an academic discipline.

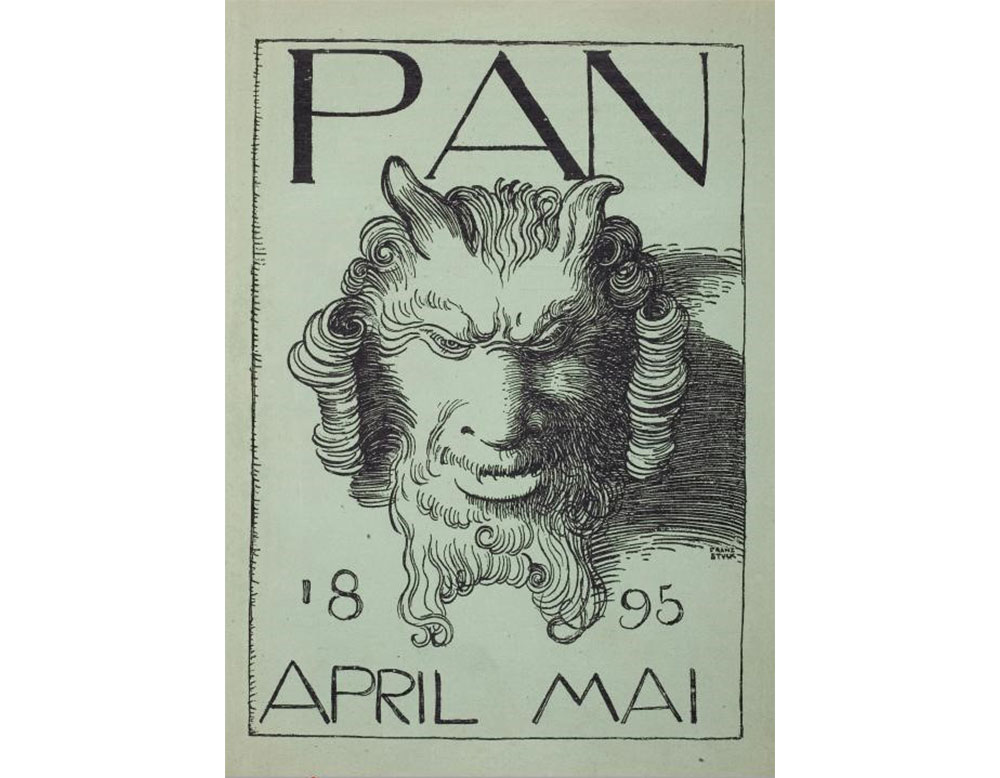

In the first episode of Kakushite kanojo wa utage de kataru: Meiji Tanbiha aesthetic school mystery book, the narrator, KINOSHITA Mokutaro, describes how he came to have a strong admiration for “Parisian artists chatting in a café” through the book Pari no bijutsu gakusei (The Art Students of Paris) by IWAMURA Toru, an art critic who brought back the latest art trends from Europe.24 Through the words of people like IWAMURA, who had traveled abroad, and through pages of imported art magazines, artists such as Mokutaro and Hakutei were exposed to Westernized artists’ lifestyles and new trends in art and literature, which they strongly admired and were greatly inspired by. In particular, Europe at the beginning of the 20th century was a period when a new trend in art, known as Jugendstil in German and Art Nouveau in French, was sweeping the entire region, and art magazines such as Cocolico in France, Jugend in Germany, and Pan were highly influential. Hosun and Pan no Kai were largely conceived under their influence.

What is important here is that Hakutei calls these European art magazines “manga magazines,” as mentioned above. In view of the fact that he associates “manga” with illustrations in his description in Seiyo Bijutsu Ron (Western art theory), it is safe to assume that “manga” referred to by Hakutei was his image of illustrations that decorated European magazines of the time in terms of form.

Hakutei’s “Honcho manga shi” (History of Japanese Cartoon) is written in a narrative style that attempts to depict the history of honcho (Japanese) manga by attributing the origin to Toba Sojo monk’s Choju-giga (Frolicking Animals) and listing manga of the time, including Toba-e, Otsu-e and Namazu-e. At first glance, this seems to be a common discussion for explaining manga in the context of the Japanese pictorial tradition, but if we keep in mind ISHII Hakutei’s understanding of manga as described above, this process seems to be based on ideas that are rather the opposite of such nationalistic theories of the origin of manga. In other words, for Hakutei, manga was nothing but a part of Western art, and his intention in discussing and creating manga was to transplant Western art to Japan at that time.

His “Honcho manga shi” (History of Japanese Cartoon) could be said to attempt to historicize “honcho” (Japanese) “manga” by retroactively applying “manga as a genre of Western art” to past paintings in Japan. His orientation toward the historicization of domestic pictorial traditions and his awareness of “form” as a method of historicization were probably inspired by a movement to construct art history in Europe at that time, which he was exposed to through Jugend and Pan. At least for Hakutei, the criteria for classifying “scroll paintings of animals and humans that belong to Kozanji temple or a Toba Sojo monk” as manga 25 were based on Western art as norm.

Before his first trip abroad at the end of 1910 (Meiji 43), ISHII Hakutei published an article titled “Nihonga to iu mono (first part)” (About nihonga Japanese-style painting) in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun newspaper dated March 26. Hakutei wrote, “I find the classic Chinese and Japanese paintings interesting as decorative painting and manga.” In other words, he is saying that traditional Chinese and Japanese paintings themselves are “decorative painting and manga.” The term “decorative painting and manga,” written at a time when the distinction between fine art and commercial art was likely to be still blurred, probably does not include MIYAMOTO’s concern with “impurity.” There may be a global consciousness to re-examine the pictorial traditions of Japan and Asia with the concepts and methods of Western art and to connect European and Asian “art.”

notes

*URL links were confirmed on August 19, 2022.